Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

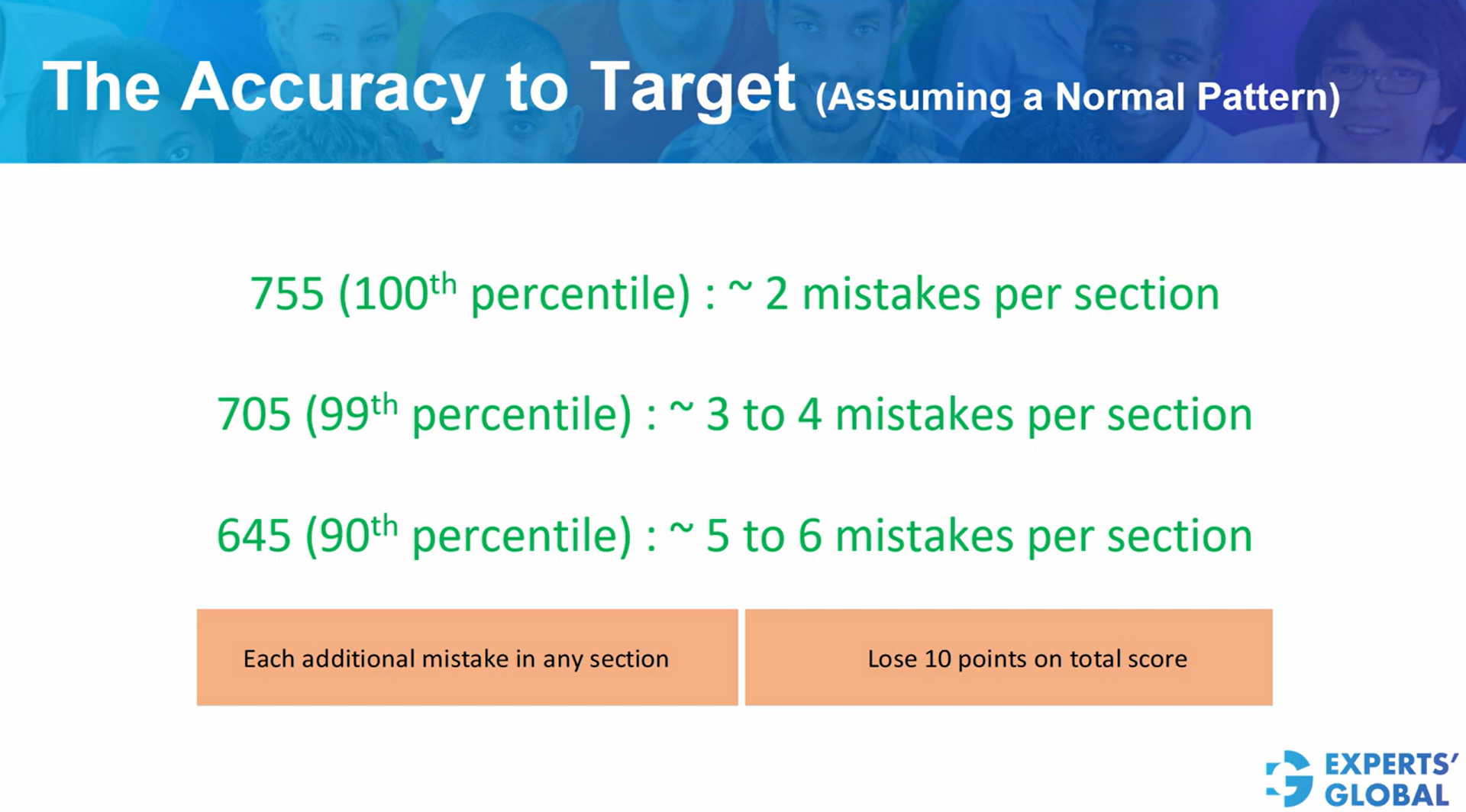

A broad estimate is that for 745 you can get 1 to 2 wrong per section, for 715 get 3 to 4, for 645 get 5 to 6, for 605 get 7 to 8, and after this each extra mistake costs roughly 10 score points.

A broad takeaway for your GMAT journey is that you do not need to get every single question correct to score well, and even a perfect score usually allows a few questions to go wrong. One practical way to use your GMAT preparation course is to set a clear target for the maximum number of questions you are willing to get incorrect across the three sections of the GMAT: Quantitative, Verbal, and Data Insights. For this, it helps to have a rough link between how many errors you make and the sectional and total scores that are likely to follow, especially when you attempt your GMAT practice tests. Please note, there are many uncertainties on GMAT scoring (such as experimental questions), so no exact table of “mistakes versus score” is possible. This article aims to offer broad, realistic estimates that help you understand the accuracy levels you should aim for in order to reach your target GMAT score.

Most aspirants live with a silent question throughout their GMAT journey: “How many questions can I get wrong and still get a good score?”. This question does not come from laziness. It comes from sincerity. You work late nights, sacrifice weekends, and yet the scoreboard in your mind keeps flashing the same doubts. Is one mistake the end of a top score? Are five mistakes a disaster? Is it even possible to reach a high percentile without near perfection? Let us answer these questions calmly, with structure and with compassion. Once you see how the scoring and accuracy really work, the exam begins to feel less like a monster and more like a system that you can understand and influence.

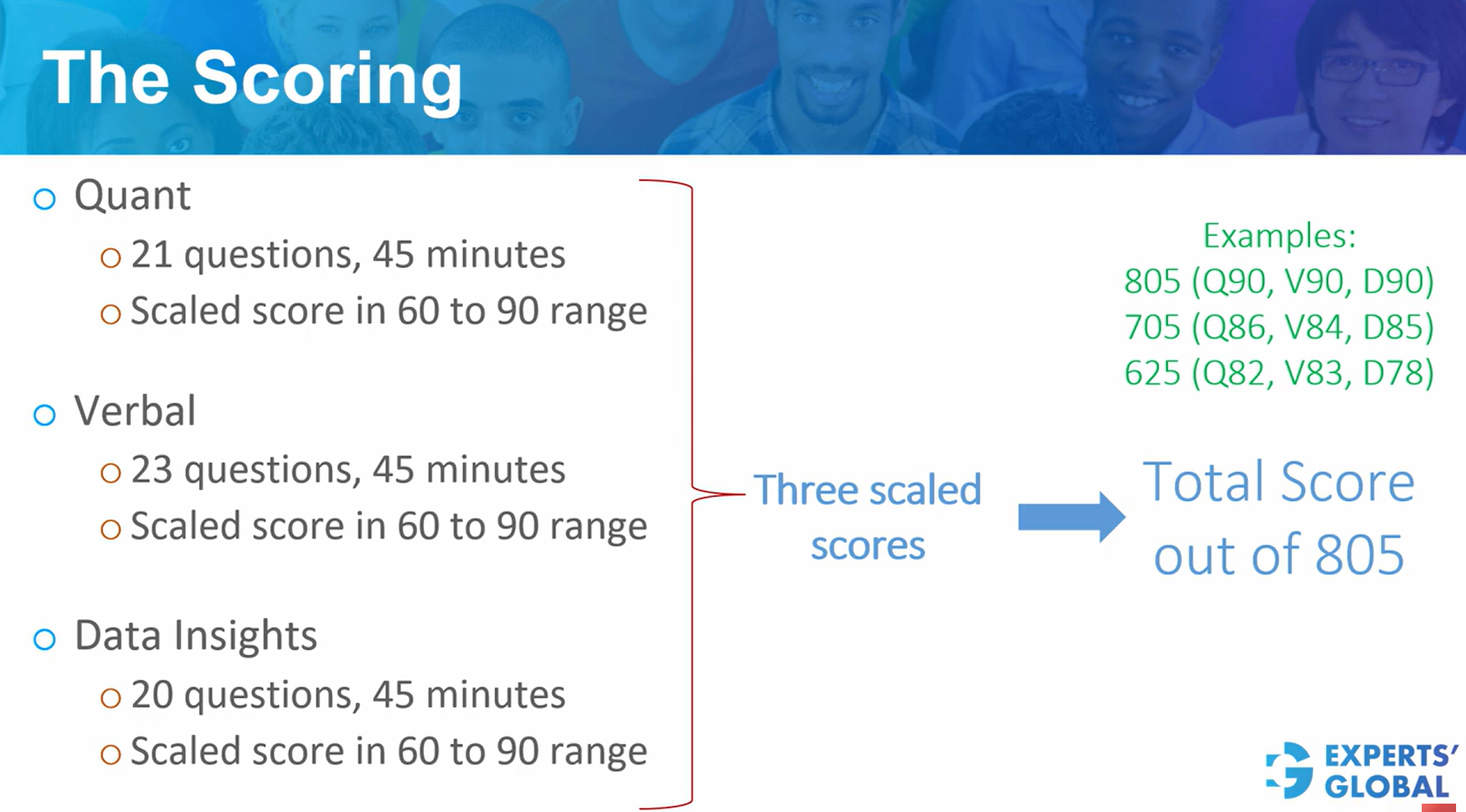

The GMAT gives you three sections:

Each section is 45 minutes long. In each section, you answer a fixed number of questions within those 45 minutes, and your performance in that section is converted into a scaled score between 60 and 90.

So, after your test, you are not only seeing one single number. You are actually seeing three sectional scaled scores, each between 60 and 90. These three scores are the raw material from which your total score is created.

If you imagine your three sectional scores as Q, V, and DI, then their sum, Q + V + DI, drives your final total score.

So, your total score always lies between 205 and 805, and it is directly linked to how strong your three sectional scores are, taken together.

Several uncertainties influence how each mistake affects your score:

Some questions on the GMAT are experimental. They are placed to test future content and are not scored. You do not know which ones these are. If you get an experimental question wrong, your score does not suffer for that particular question, even though you experience it as a mistake.

The order in which you get questions right or wrong also matters. The first thirty percent of questions in a section tend to carry slightly more importance for determining the pattern of difficulty you will see later. Very weak performance in the first stretch can pull your score down more sharply.

The penalty for missing a relatively easy question is often more severe than the penalty for missing a very hard question. If you make most of your mistakes on easier items, your score suffers more than if the same number of mistakes had occurred on tougher items.

Consecutive mistakes can also hurt more. A cluster of wrong answers signals the algorithm that your current difficulty level may be too high, and the test may respond in a way that reduces your score more sharply than scattered, isolated mistakes would.

Because of these factors, there is no perfectly rigid chart that says, for example, “Seven wrong answers in this exact pattern will always equal this exact score.” What we can build, responsibly, is a set of ballpark estimates that assume a normal pattern: mistakes spread out across the section, difficulty reasonably matched, and no extreme good or bad luck.

Under the assumption of a normal pattern – that mistakes are distributed reasonably and the performance is not distorted by extreme luck on experimental items – we can estimate in terms of typical ranges. These are ballpark estimates, but they are powerful enough to guide your strategy.

As a rough rule of thumb, each additional mistake in any one section tends to cost around 10 points on the total score. Once again, please note, these values are not binding; rather, these are broad estimates to help you plan your target accuracy with respect to your target scores. Still, they give your mind something very precious: a sense of control.

In the end, this discussion about mistakes is really a discussion about how growth works. GMAT preparation teaches you that progress is not a straight line, and that a single imperfect step rarely defines the journey. The MBA application consulting process reinforces the same lesson. You learn to shape your story with care, to build on what is strong, and to improve what needs attention without losing confidence in your direction. MBA education continues this pattern, offering a space where thoughtful trial, honest reflection, and steady refinement matter more than flawless execution. Life follows a similar rhythm. You move forward by engaging fully with each attempt, understanding what each error reveals, and choosing your next step with intention. Let this perspective stay with you. Your aim is not to avoid every mistake but to respond to each one with clarity, calm, and a sense of purpose.