Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

The quantitative section on the GMAT is one of the three sections on the exam and therefore contributes to one-third of your overall score. In addition to this direct contribution, the concepts learned during quantitative section preparation also contribute indirectly to roughly half of the questions in the Data Insights section. For this reason, thorough and end to end coverage of all GMAT quantitative concepts is an essential component of any reliable GMAT preparation course. This page provides an overview of virtually all GMAT quantitative concepts, with links to detailed study resources, including subtopic-specific video lessons, theoretical lessons, conceptual videos, and practice questions — all available for free on our website. Happy learning!

Number properties are the backbone of the quantitative section on tests like the GMAT. Nearly half of the questions in this section, either directly or indirectly, rely on number properties. Mastering these concepts will not only boost your performance in the quantitative section but also improve your ability to tackle quant-based problems in the Data Insights section. Becoming comfortable with numbers helps you think and calculate faster and more accurately, making a noticeable difference in your overall GMAT performance. Because of its importance, number properties should be one of the first topics you focus on in your GMAT prep and apply the learnings in your general practice as well as GMAT mock tests.

On the GMAT, all numbers you encounter are real numbers, meaning you won’t work with complex numbers. These real numbers can be divided into two main categories: rational and irrational. Rational numbers are those that can be expressed as P/Q, where both P and Q are integers and Q is not zero. In contrast, irrational numbers cannot be written as fractions. Rational numbers are further divided into fractions and integers, with integers being classified as either even or odd, and also as prime or non-prime. Understanding these classifications clearly will help you avoid errors on test day. The video below explains the classification of numbers in a straightforward and easy-to-follow manner in just a few minutes.

In the GMAT quant section, some of the most commonly encountered numbers come with unique characteristics that often confuse test-takers. The numbers 0, 1, and 2 may seem simple, but each has a distinct property that can affect the outcome of a question. The number 0 is an even integer, which many students mistakenly believe is not the case. The number 1 is not considered a prime, despite often being treated as one. The number 2 is special as it is the only even prime number. While these may seem like minor details, on the GMAT, they can make a significant difference. The following short video clearly explains these exceptions and demonstrates how they may be tested in the exam.

On the GMAT, even the simplest concepts can hide unexpected challenges. Take the rules for even and odd numbers, for example. While they seem basic and almost too simple to focus on, when applied cleverly in GMAT questions, they can expose nuances that many test-takers overlook. The video below explains this concept in a clear way and emphasizes the potential traps within this straightforward yet captivating topic.

(Example: What is the units digit of the numeric value of 14389 x 5294 x 4238 x 7996 x 423 x 727 x 863?)

In GMAT Quant, some questions look time-consuming the moment you see them. A long chain of numbers being multiplied can feel impossible to manage. The common impulse is to start multiplying everything out, and that is exactly where many students waste valuable time. In reality, you almost never need the full product. What really matters is the units digit. When you focus only on the last digit of each number, you can predict how the product ends without dealing with the rest. Simple pattern awareness, like spotting a 2 and a 5 together, instantly tells you the product must end in 0. Building this kind of number sense separates a steady, prepared test taker from someone who feels overwhelmed. The following short video explains this idea clearly and shows how it can appear on the GMAT.

(Example: What are the last two digits of the numeric value of 432 x 1977 x 5423 x 999 x 805 x 7797?)

Some GMAT Quant problems are designed to overwhelm you with their sheer size. A long product of large numbers can make it feel impossible to calculate within the test’s time limits. Yet the GMAT does not expect full multiplication. It rewards sharp observation and smart shortcuts. When the question asks for the last two digits of a huge product, you do not need to expand every number. The key is to track only the final two digits of each term and notice the patterns that show up.

(Example: Finding the units digit of 2792)

At first glance, numbers such as 2792 may look overwhelming, yet the GMAT never expects you to calculate too much. What truly matters is your ability to break the task into calm, logical steps. The method rests on two central ideas. First, only the units digit of the base matters. Second, units digits repeat in four-step cycles, so dividing the exponent by 4 becomes the real shortcut. Once you know the remainder, you simply raise the last digit to that power to get the answer. Even special situations, such as a remainder of 0 or a negative result after subtraction, stay easy to handle when your concepts are clear. The following video explains this concept in a simple way and works through a few GMAT-like examples…

(Example: Finding the number of factors of 900)

As you prepare for the GMAT, getting comfortable with factor-based questions is an important step toward real confidence. Instead of writing out factors one by one, which is slow and invites errors, a smarter method is to use prime factorization. When you express a number as a product of prime factors, adjust the exponents, and then combine the results, you can find the total number of factors with both speed and accuracy. You need to ensure unique prime bases, add 1 to the power of each prime base, and multiply to get the number of factors. The following video explains this concept in a simple way and walks through a few worked problems…

(Example: Finding the highest power of 25 that divides 500!)

As you prepare for the GMAT, getting comfortable with factorials helps you notice some beautiful number patterns. One especially elegant application is finding the greatest power of a given divisor that is contained within a factorial. Instead of focusing on the entire number, you break the divisor into its prime factors and count how many times each one appears. With a bit of practice, this approach starts to feel natural, fast, and very dependable. The short video that follows captures this concept clearly and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

(Example: Finding whether 159/120 will terminate or repeat)

During your GMAT preparation, you start to notice that the simplest concepts often create the biggest impact. Terminating fractions show this clearly. What looks like routine calculation begins to reveal rich patterns when you slow down and observe with care. Deciding whether a fraction terminates or repeats depends less on long computation and more on clear thinking. A decimal terminates when its denominator has no prime factor other than 2 and 5; otherwise, it repeats. The following short video explains this idea simply and works through GMAT-like problems.

Mastering the divisibility rules can significantly boost your speed and accuracy, especially for remainder-based questions on the GMAT. This concise, engaging video covers all the essential divisibility rules, demonstrating their practical application and explaining how these concepts are tested on the GMAT.

(Example: Finding the remainder of 623 x 389 x 8297 x 6253 with 25)

As you move through your GMAT preparation, remainder problems give you a beautiful glimpse of how simple ideas can manage large expressions. Instead of doing heavy multiplication, you only need to track the remainders and combine them with care. This way of working saves time, improves accuracy, and strengthens logical clarity. The short video below gives a simple walk-through of this concept and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

(Example: Finding the remainder of 3483 when divided by 8)

In these questions, the goal is to find the remainder of a large power both quickly and correctly. In your GMAT preparation course, you follow a clear routine. First, reduce the base by the divisor. Then test small powers of this reduced base until one gives a remainder of +1 or −1, and treat that exponent as the cycle length. Next, shorten the original exponent using this cycle and replace the large power with 1 or −1. If the result is −1, add the divisor to make the remainder positive. For any extra factors, repeat the reduce and shorten steps. The following short video presents this concept clearly and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

(Example: Integer N leaves remainder 83 when divided by 90; what remainder will P leave when divided by 18?)

In your GMAT preparation, a powerful habit is to write numbers in a neat, structured form. Remainder questions become simpler when you express a number as N = d × q + r and then observe how this form behaves as the divisor changes. This section focuses on a pattern the GMAT particularly likes: you are told that N leaves remainder r when divided by d, and you must find the remainder when N is divided by a factor or a multiple of d. We reduce the large expression, cancel what vanishes, and track the smaller remainder carefully, step by step. The short video below captures the essence of this concept and shows how it can appear on the GMAT. The following brief video helps you feel at ease with this idea and shows how the GMAT can test it.

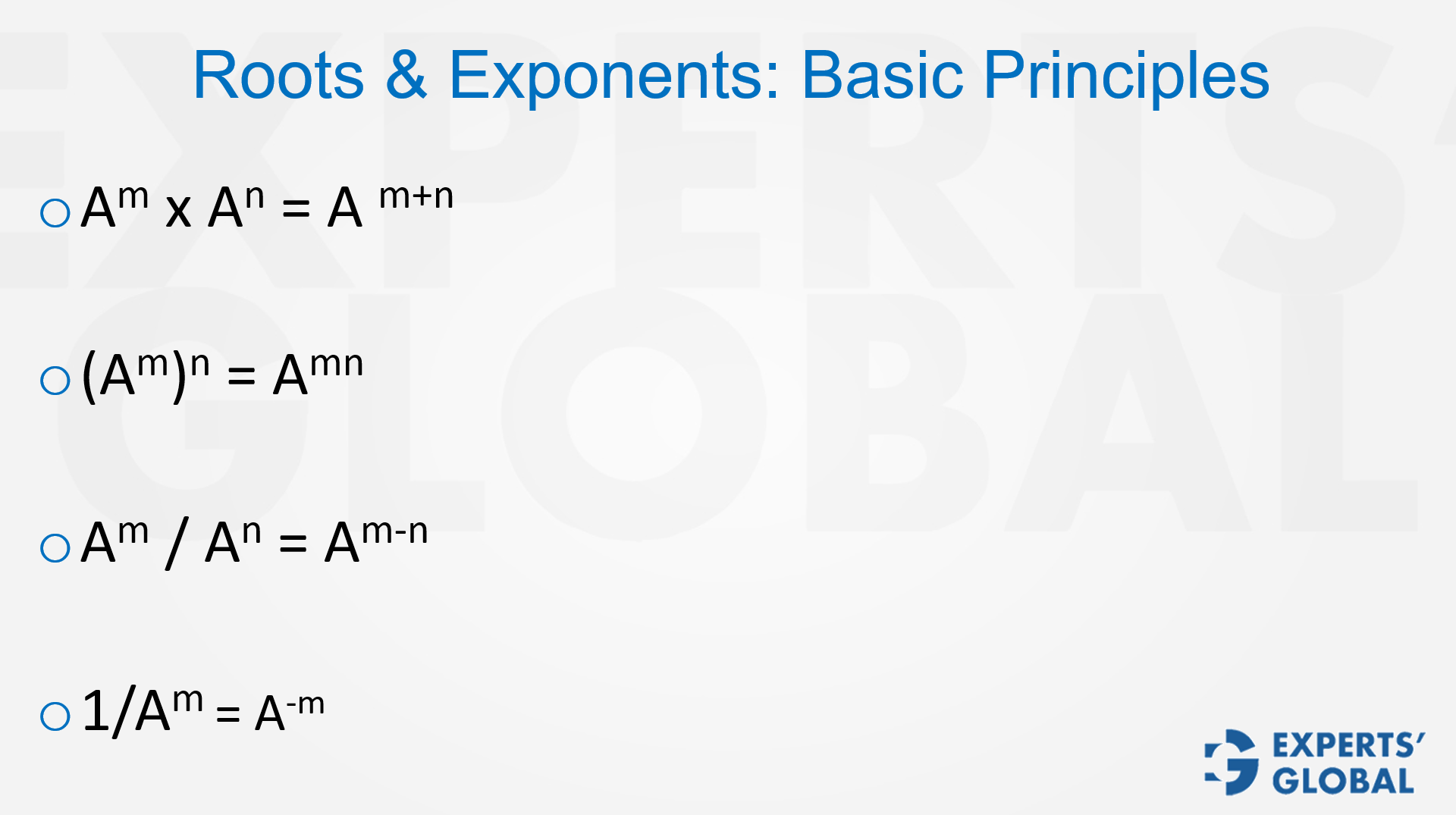

Roots and exponents, also called surds and indices, focus on writing numbers as powers and their matching roots, such as square roots, cube roots, and higher order radicals. The following slide brings together the core principles that guide roots and exponents. These rules work best when the bases of the terms involved are the same, and, in many questions, choosing or recognizing a prime base proves especially helpful. Take a moment to review these principles and move on for delving deeper into the topic.

Looking for prompt GMAT prep? Check out our GMAT crash course

(Example: If 25^2x = 125^x – 3, x = ?)

Rely on a steady, dependable approach to exponents and roots: rewrite each expression as a power of the same prime base. Convert roots into fractional exponents, combine like powers, match the bases, and then set the exponents equal to solve for the variable. The brief video below introduces this concept gently and shows how the GMAT generally tests it.

[Example: (5^1000 + 5^1001 + 5^1002 + 5^1003) ÷ (5^999 + 5^1000 + 5^1001 + 5^1002) = ?]

One of the GMAT’s favorite ways to test higher order thinking is by presenting intimidating expressions with very large powers. The exam is not testing your ability to grind through huge calculations; it is measuring how clearly you spot simplifications. Whenever you see very high exponents in both the numerator and the denominator, the problem is often designed so that the greatest common power can be factored out and removed. The short video below reinforces this idea and shows how it can appear in GMAT questions.

On the GMAT, rationalization means removing square roots from denominators by multiplying the numerator and denominator by the conjugate, which turns (a + √b) into (a − √b) and creates an equivalent fraction with no radicals in the denominator. The following video explains this concept and takes up a few GMAT-style problems involving rationalization.

Overlapping sets problems describe situations where people or objects belong to more than one group at the same time, and the goal is to understand how these groups overlap or intersect. These questions require you to organize information clearly and reason through counts with care. Getting comfortable with this idea is an essential part of any end-to-end GMAT preparation course. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few GMAT-style worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

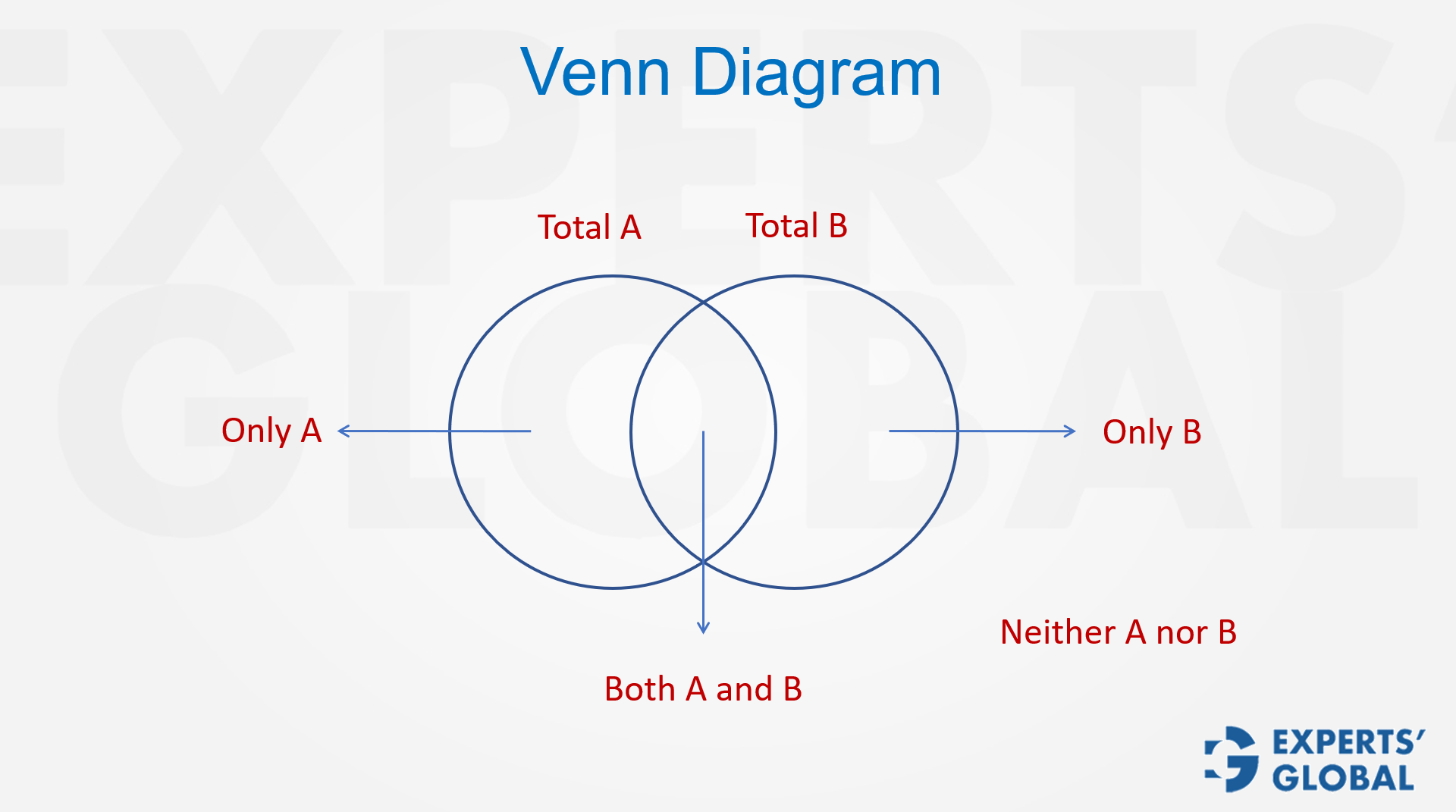

Venn diagrams are one of the simplest, yet most powerful tools for handling set-based questions on the GMAT. The key idea is to place the information into a clear layout so nothing gets missed and every part of the set appears. This approach keeps you from getting lost in the wording and lets you rely on a neat visual picture instead. The following short video explains and demonstrates this approach, then prepares you to use it across GMAT drills, sectional tests, and the full length GMAT mock tests.

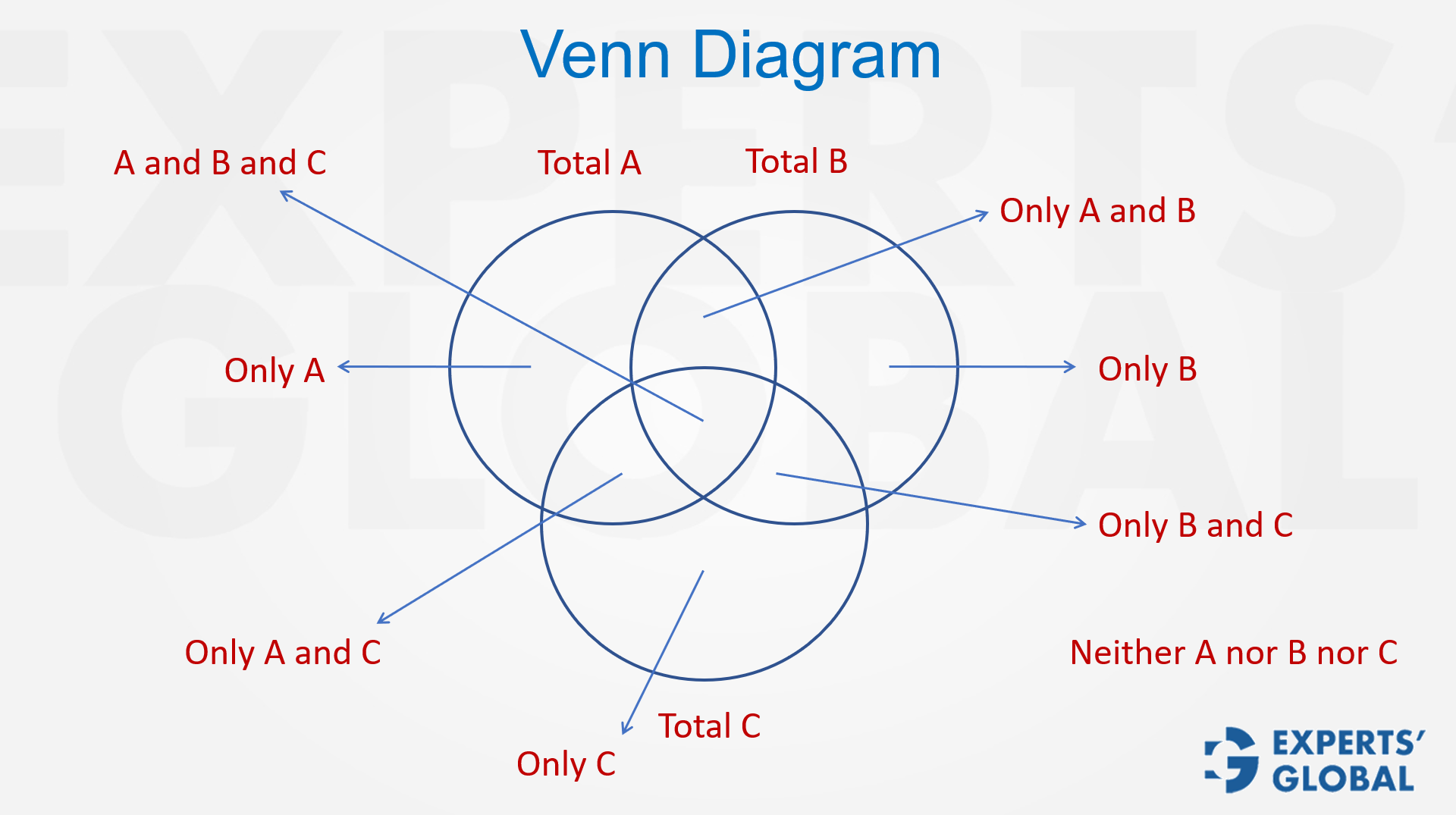

When a problem involves three sets, it becomes both interesting and challenging. A well-structured three-circle Venn diagram is the best way to handle such situations. Start by placing the totals outside each circle, then carefully add the overlapping values, beginning with the most crucial part: the region where all three sets intersect. Once this central area is set, the rest of the diagram falls into place. Each remaining section, whether representing pairs, single sets, or the outside area, can then be filled in a clear, methodical manner. With the diagram complete, the follow-up questions become much simpler. The following video breaks down this concept with simple reasoning and demonstrates how it may appear on the GMAT.

Wish to know your current GMAT level? Register for a free full-length diagnostic GMAT test

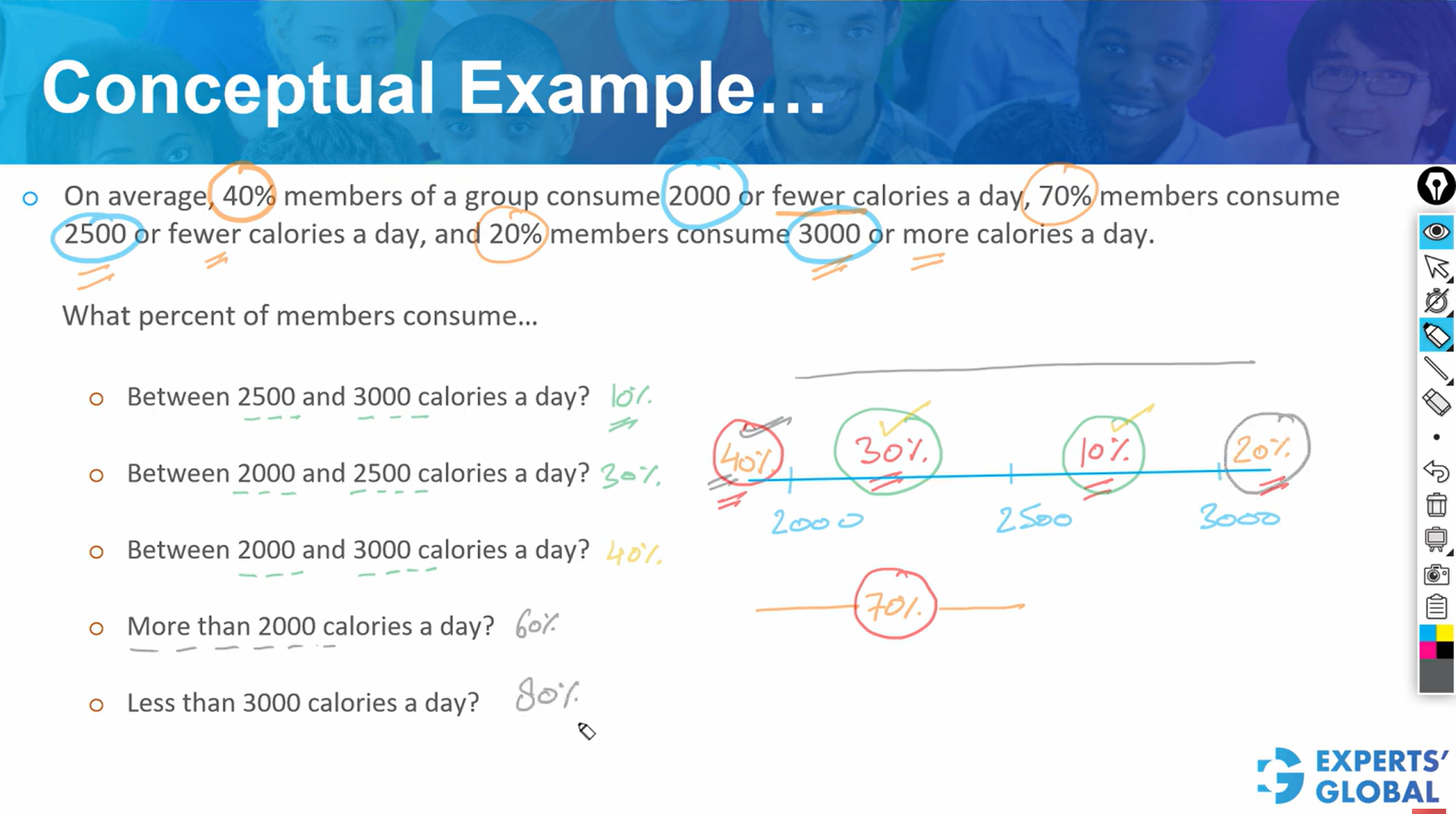

A line diagram is a simple number line that shows how ranges overlap, stay separate, or come together, making it an excellent tool for solving GMAT questions on overlapping sets. It turns complex verbal descriptions into a clear visual layout, helps you mark boundaries with precision, and lets you read each segment as a share of the whole. In the conceptual video below, you see how line diagrams are built step by step on overlapping set problems, so you can use this tool efficiently and calmly under exam time pressure.

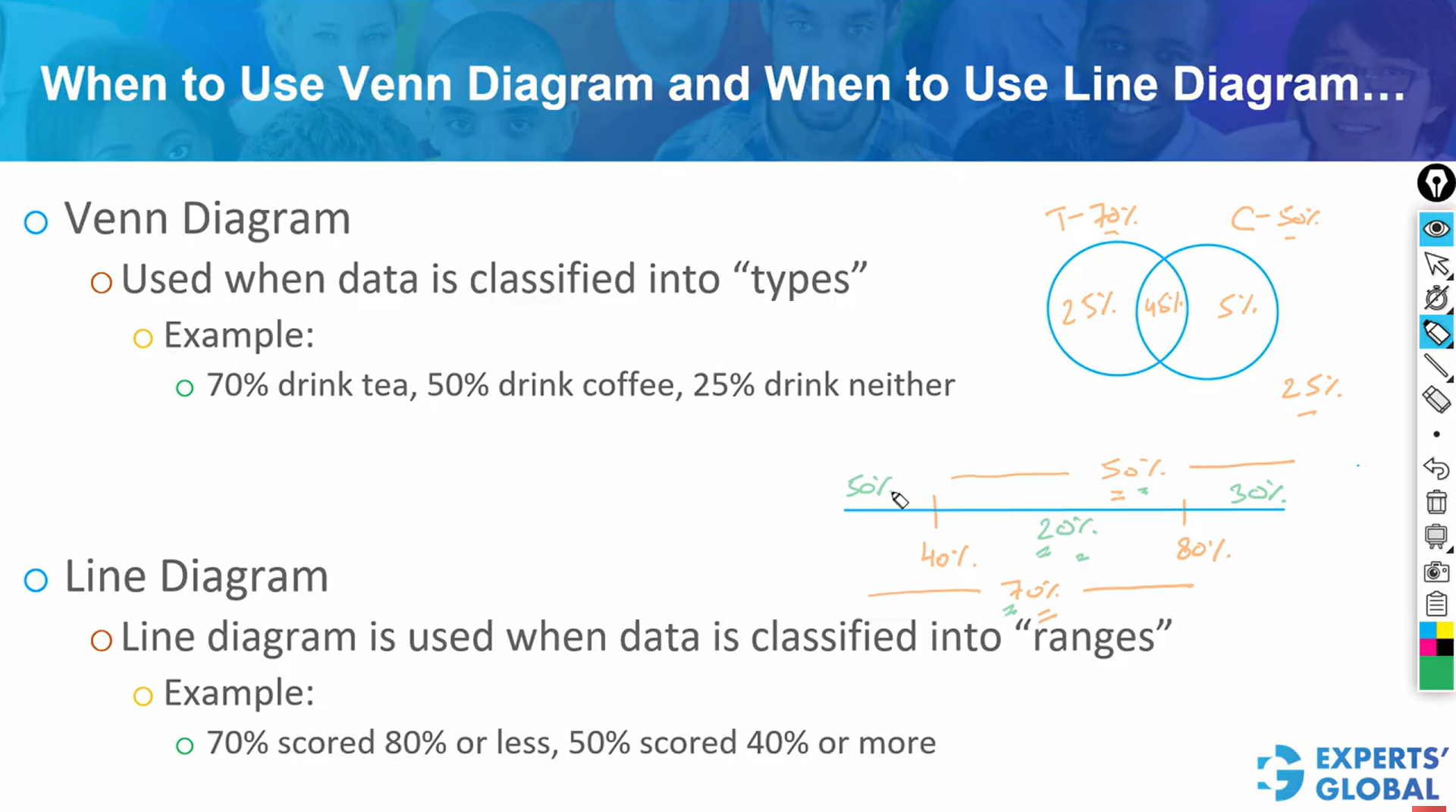

Choosing between a Venn diagram and a line diagram becomes much simpler once you understand the kind of information each one is meant to capture. A Venn diagram fits naturally when the data is divided into categories or types, such as people belonging to different clubs or products falling into different segments. A line diagram works better when the information lies on a numerical range, such as scores, ages, or time intervals that partly overlap. In the conceptual video below, you see clear examples of both tools on overlapping set problems, so you can decide quickly which diagram to use and solve GMAT questions efficiently in the exam setting.

Percentages, mixtures, and alligation form a closely connected cluster of ideas on the GMAT. Percentages express a part of a whole on a scale of 100. Mixtures describe the result of combining two or more components. Alligation provides a quick way to handle many weighted average situations within mixtures and percentages. A solid understanding of these ideas is an essential part of any comprehensive GMAT preparation course. This page offers an organized, subtopic-wise playlist for steady preparation of this concept, along with a few worked examples.

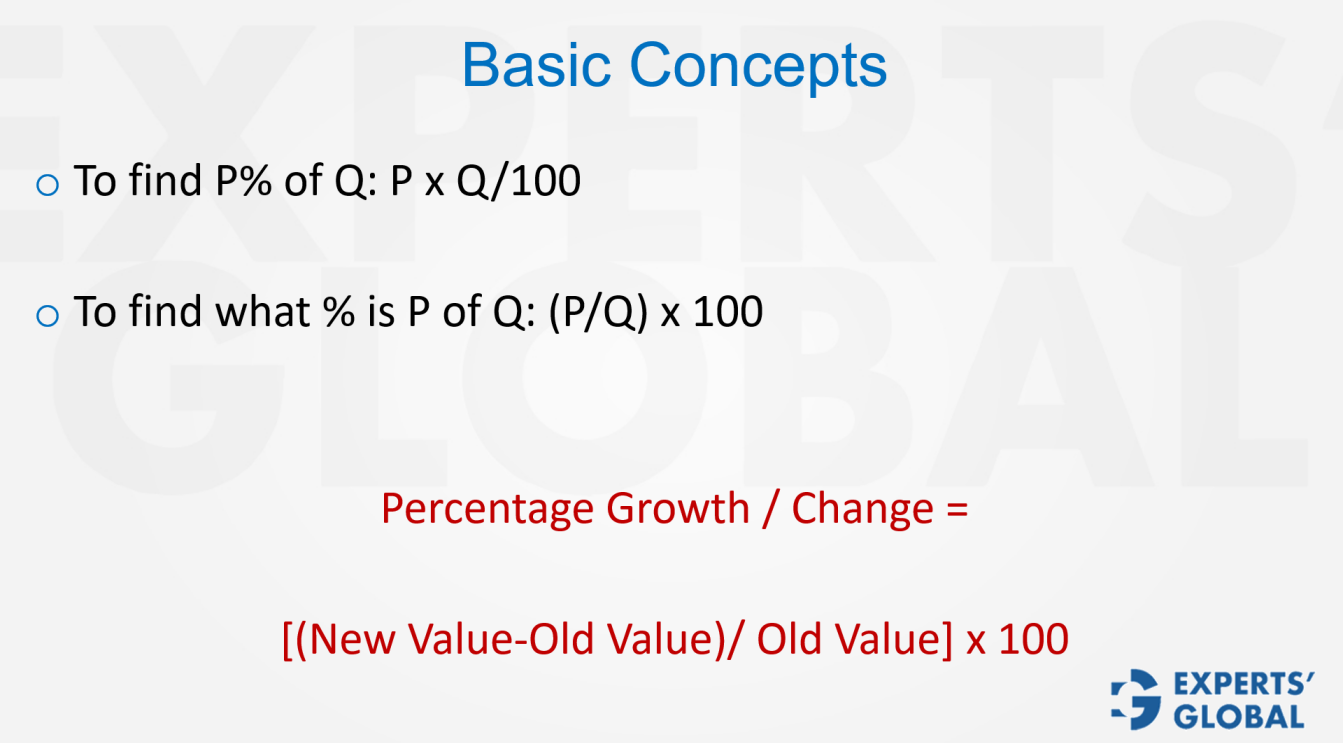

A percentage represents the “part out of 100.” To find a percentage, divide the number (part) by the total (whole), then multiply the result by 100. That means (part ÷ whole) * 100.

Example: 30 out of 50 is (30 ÷ 50) * 100 = 60%

Percentage change shows how a value changes from its starting point. Use: [(new value – old value) ÷ old value] * 100.

Example: value increases from 50 to 80, change = [(80 − 50) ÷ 50] * 100 = 60% increase.

From 80 to 50, change is 37.5% decrease.

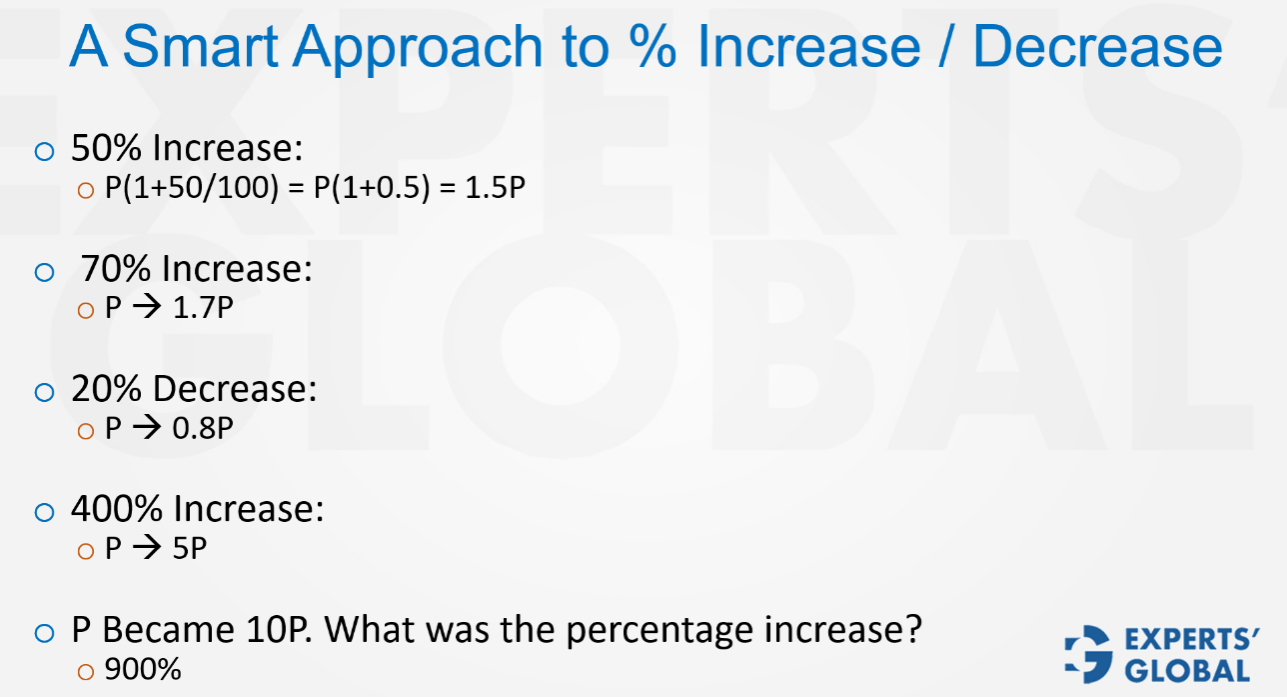

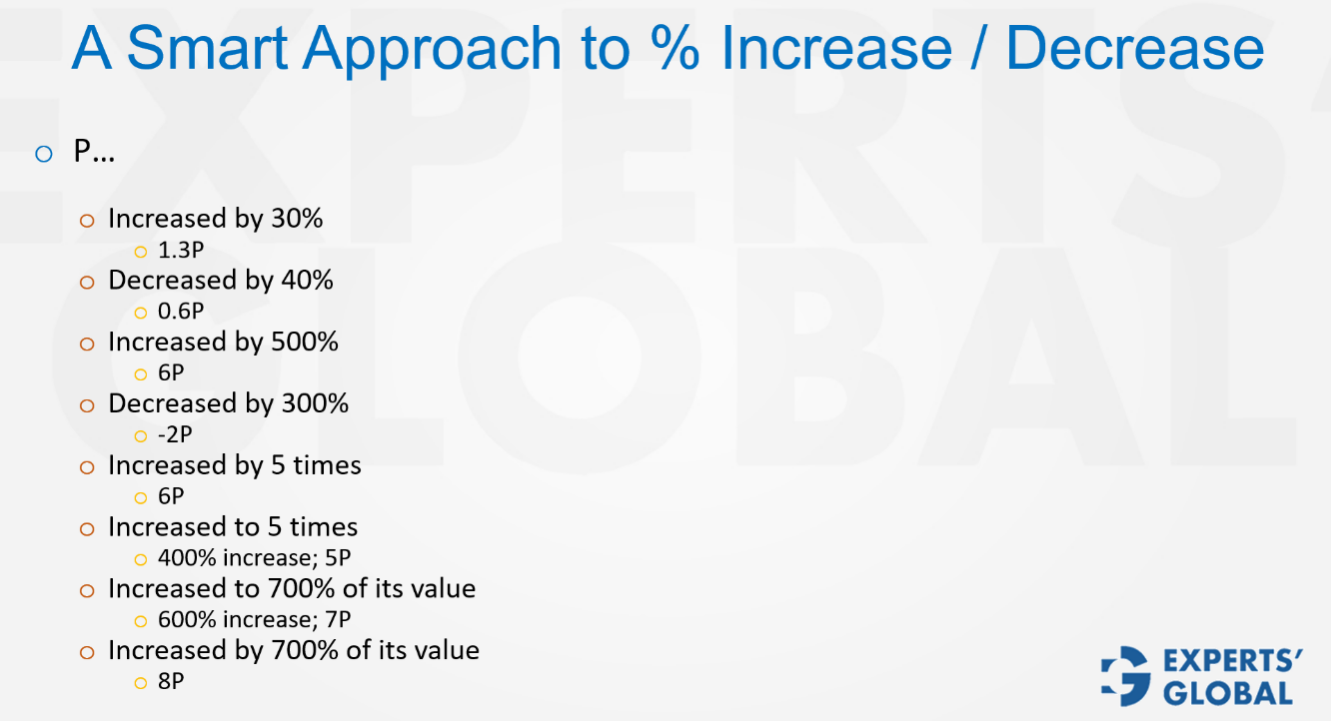

Percentage questions may look easy at first sight, yet many test takers lose marks because of small misunderstandings in interpretation. You can handle a percentage increase or decrease in just a few seconds when you use a direct method instead of stretching the work into long calculations. For example, a 50% increase does not need fractions or elaborate steps; it simply means the original quantity becomes 1.5 times its value. A 20% decrease means the quantity becomes 0.8 times the starting value. Once you see this pattern clearly, the entire topic shifts from confusing to natural. Just as important is the difference between “increase by” and “increase to,” a distinction that many test takers blur when exam pressure builds. This short video explains the method, shows it solving representative questions, and equips you to apply it in GMAT drills, sectional tests, and your full length GMAT practice tests.

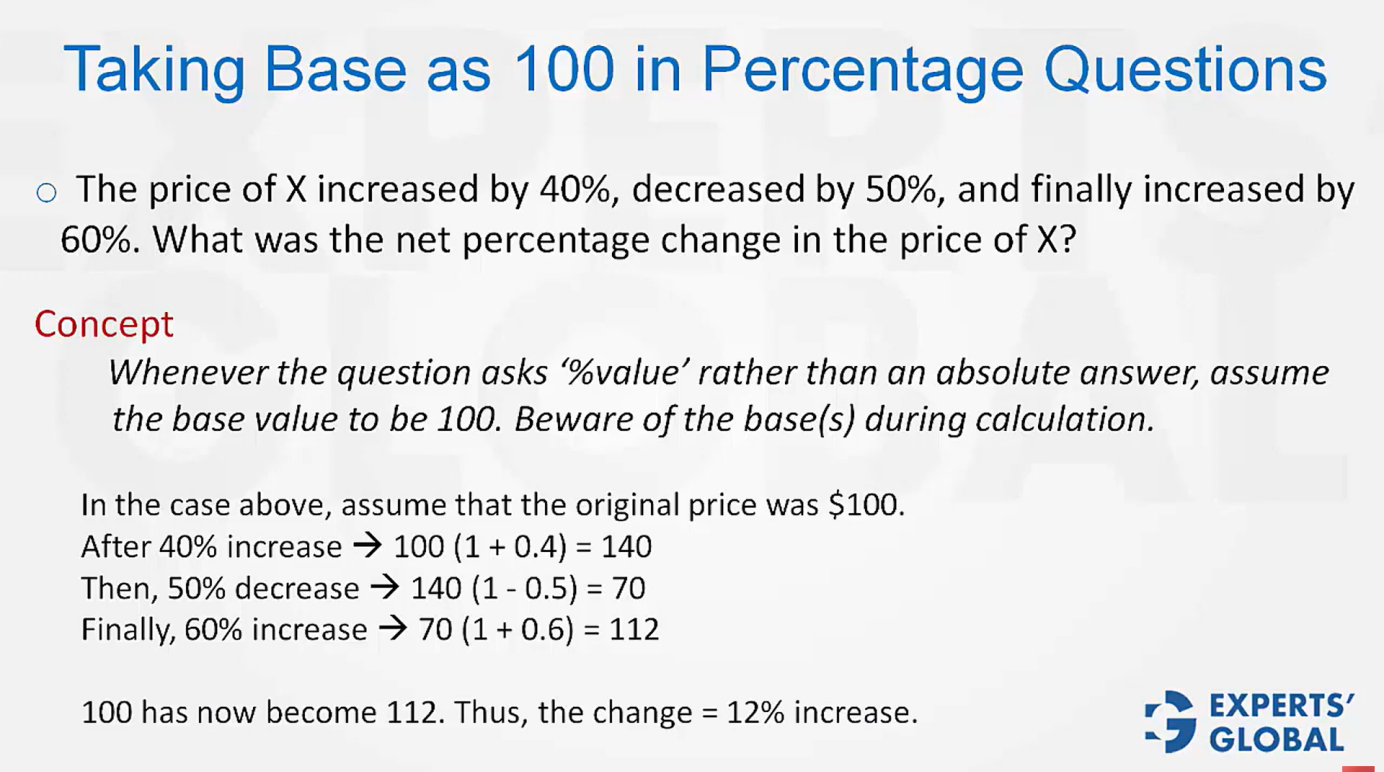

The real difficulty in percentage change questions lies not in the arithmetic but in the shifting base that each new percentage uses. A 40% increase followed by a 50% decrease is very different from simply subtracting 10%. Each percentage applies to the updated value, not to the original one. This is where many students slip, and this is exactly what the GMAT likes to test. An efficient approach is to assume a base value of 100. This keeps the numbers friendly and makes it easy to see how successive percentages build on one another. A 40% decrease after a 40% rise, for example, does not take you back to your starting point but to a smaller value instead (100 → 40% increase gives 140 → 40% decrease brings it down to 84). The following brief video walks you through this idea and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

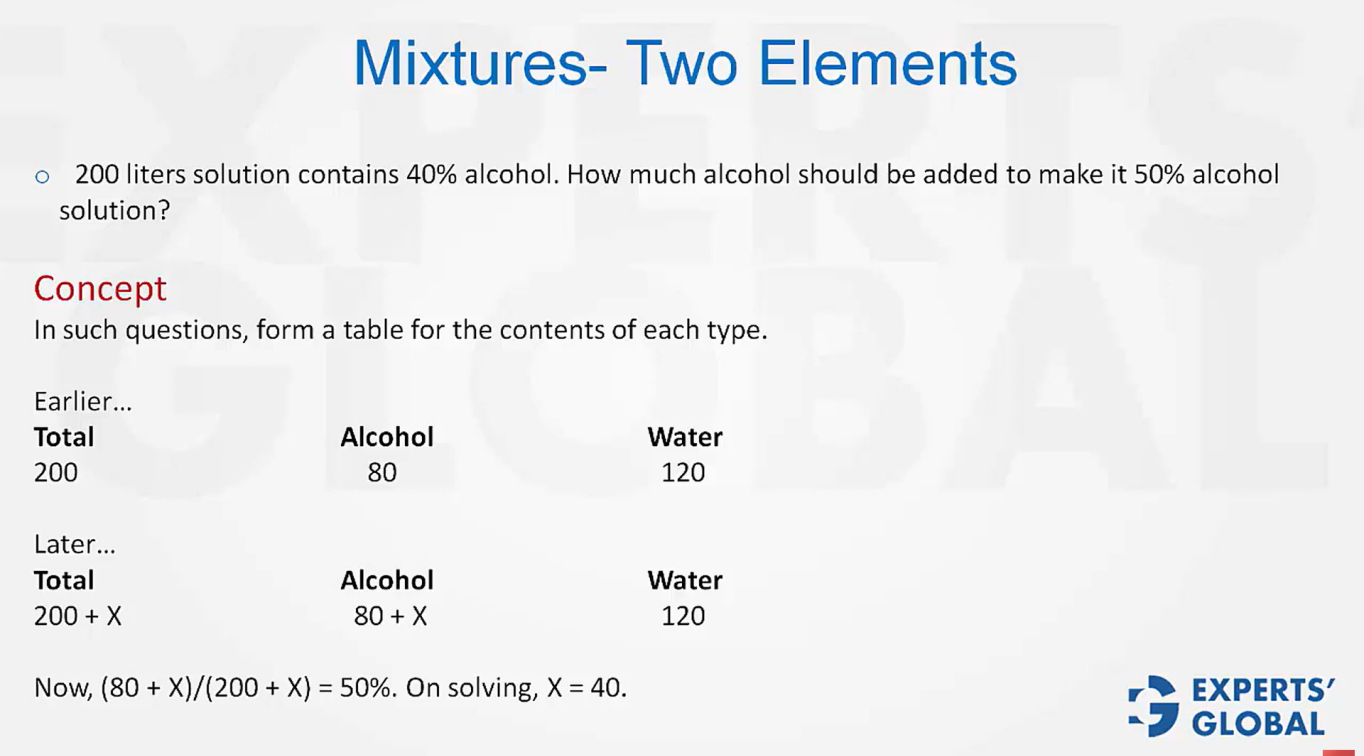

Mixture and solution questions are a staple of aptitude tests and GMAT style quantitative reasoning, and they deserve a firm place in your GMAT prep. They test how well you balance percentages, proportions, and overall structure. The main difficulty is that when you add or remove one ingredient, the total quantity changes, and the percentage composition shifts with it. If you miss this, you step straight into the trap of wrong options. A clear and dependable way to handle these problems is to set up a simple table that captures the amount of each component. The short video below clarifies this idea and shows how the GMAT can test it.

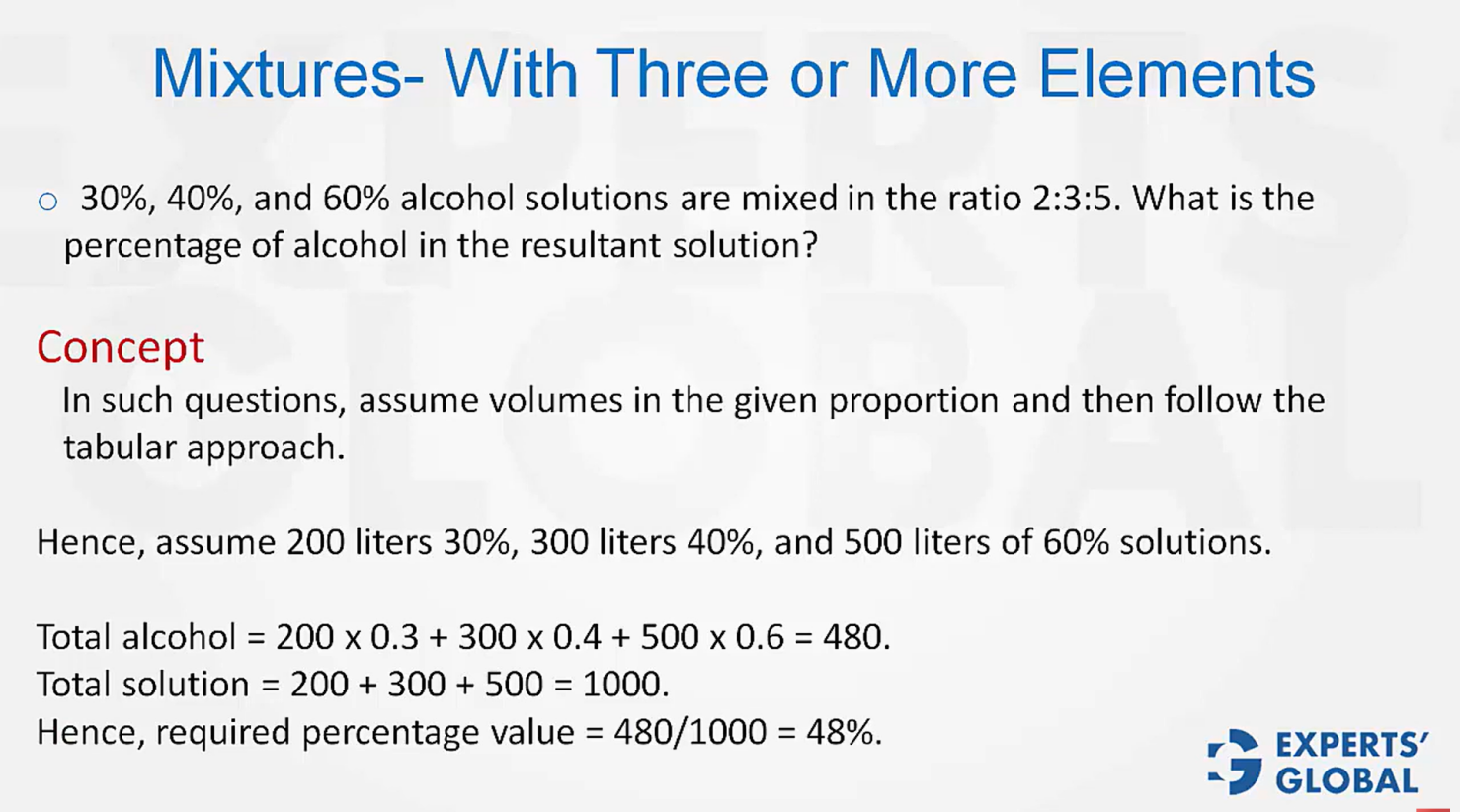

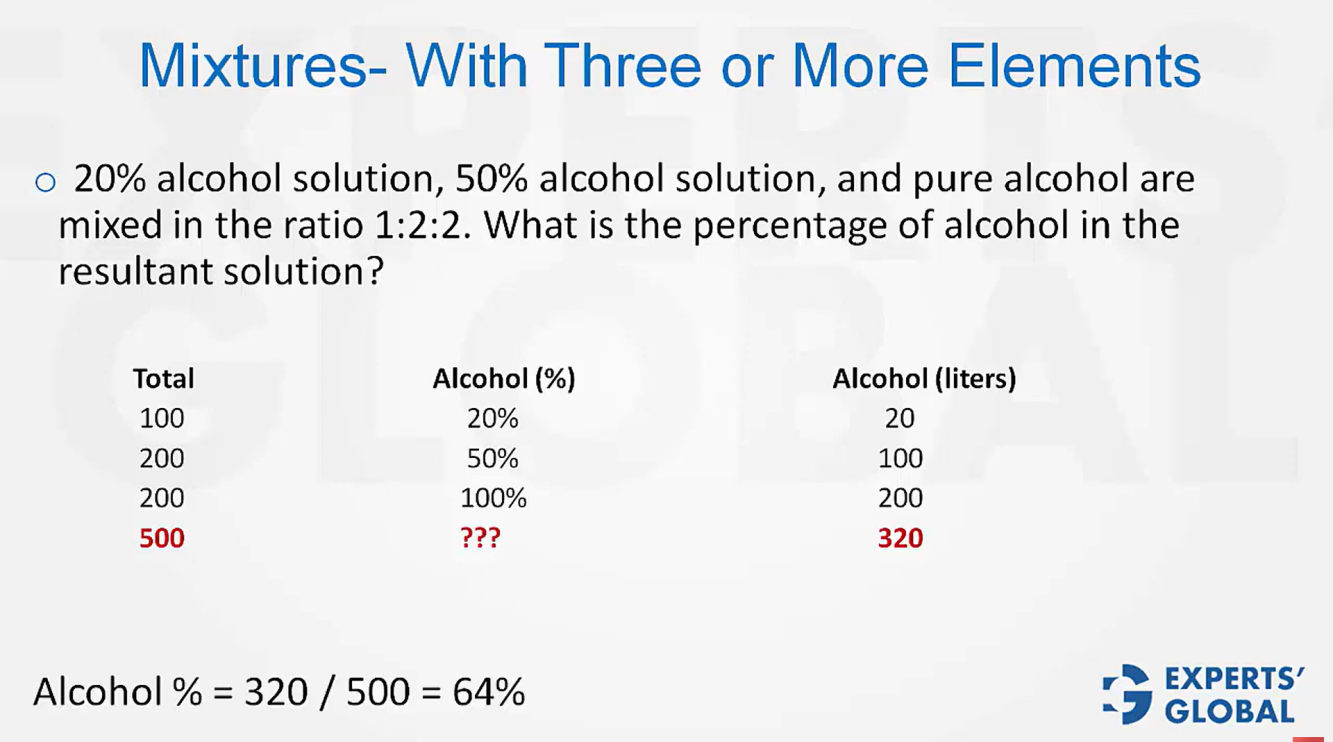

Mixture and ratio-based solution questions often look easy at first, yet they can quickly confuse you if you work without a clear structure. The safest method is to assume convenient numbers for the given ratios and then use a simple table to track total volume, alcohol content, and water content. This habit reduces errors and keeps each step transparent. For example, when three solutions mix in the ratio 2:3:5, it helps to assume volumes of 200, 300, and 500 liters, respectively. Once these values are set, applying the given percentage concentrations becomes straightforward, and you can calculate the absolute amounts of alcohol. Add these quantities and divide by the total volume to get the overall concentration directly. In this way, such problems train you to handle ratios, percentages, and weighted averages in a calm, structured manner. The following short video makes this idea easy to follow and shows the ways it can be tested on the GMAT.

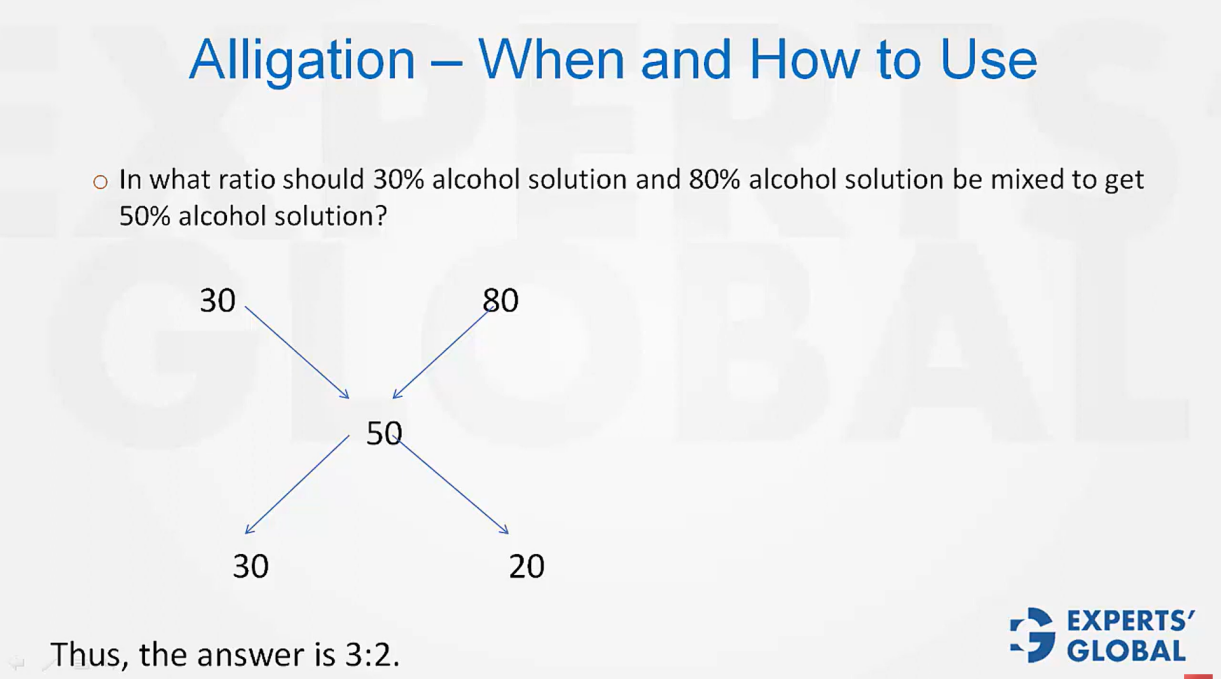

Many students feel confident with weighted average problems on mixtures, but they start to struggle when the question flips: instead of asking for the final concentration, it asks what ratio two components must be mixed in to reach a desired concentration. This is exactly where alligation becomes powerful. Alligation is a structured technique that removes the need for trial and error. It lets you place the two given concentrations and the target concentration in a simple layout, take the differences, and move straight to the required mixing ratio. For example, if a 30% solution and an 80% solution blend to create a 50% solution, alligation shows the ratio as 3:2 almost instantly, without long calculations. The brief video that follows explains this idea clearly and shows how it might be tested on the GMAT.

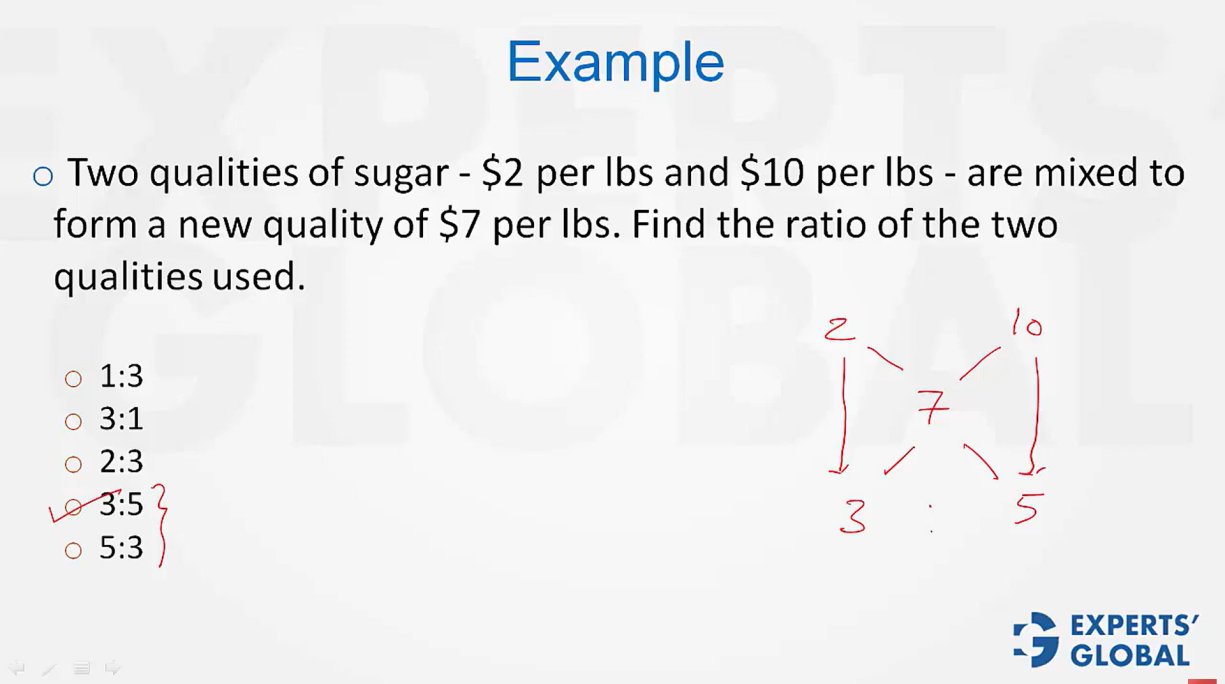

Alligation helps you find the required ratio right away when two different strengths blend to produce a specific final strength. The idea is simple: place the two given values on either side, write the desired value in between, and then take the diagonal differences. These differences directly give the ratio of the two components. For example, if the original values are 2 and 10 and the target is 7, the differences are 5 and 3, which give the ratio 3:5. Approaching problems this way brings clarity and helps you avoid careless slips, especially when exam pressure is high. The short video below breaks this idea down and shows how it can appear on the GMAT.

Ratios compare two quantities. Proportion describes the relationship between two equal ratios or between a part and the whole. Variation explains how one quantity changes when another changes. A proper understanding of these concepts is an essential part of any comprehensive GMAT preparation course. This page offers an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for steady preparation of this concept.

Proportion questions sometimes unsettle students because they look simple on the surface, yet one small hidden idea changes everything. The key insight is that a ratio such as A:B = 2:5 does not say that A is 2 and B is 5. It says that A and B keep this relationship through common multiples, whether the values are large or small, positive or negative. Seeing this clearly is the starting point for handling proportion-based questions with speed and accuracy. A common GMAT pattern changes A and B by certain amounts and then sets them equal to a new ratio. When you express each term in relation to a single constant, these questions open up in a clean, straightforward way. The short video below presents this approach, shows how it works on real GMAT questions.

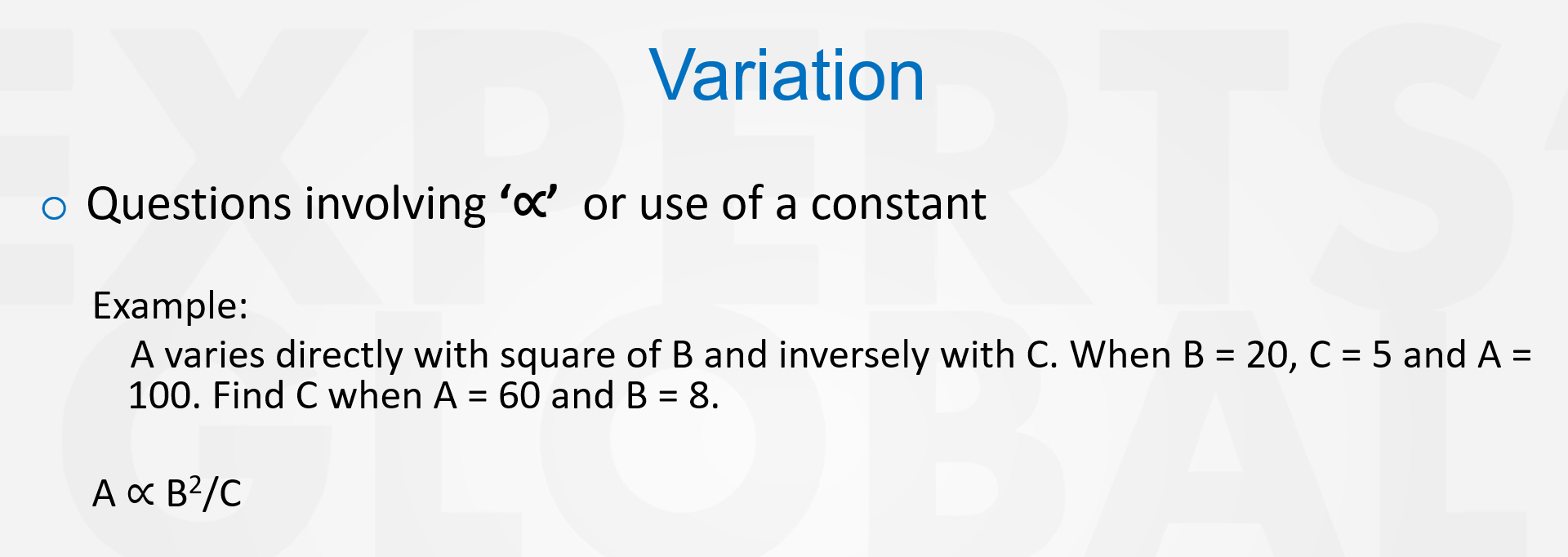

Variation questions on the GMAT grow naturally out of ratio and proportion problems, but they ask for a deeper sense of how quantities relate to one another. Instead of working only with simple ratios, you now work with the ideas of constants and proportionality. A quantity may change directly with one variable, inversely with another, or through a blend of both. The central task is to turn these worded relationships into clear mathematical statements and then solve them calmly, step by step. For example, if A varies directly as the square of B and inversely as C, you write this as A ∝ (B² / C). When you replace the proportionality sign, a constant enters the equation, and you can plug in values to find unknowns. The brief video that follows explains this idea step by step and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

The concept of profit and loss explains how the value of a transaction changes between cost price and selling price, while interest refers to the extra amount earned or paid when money is borrowed or invested over time. These two ideas form a central part of commercial arithmetic and appear often in quantitative reasoning. This section offers you a clear, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, to help you prepare for this concept with confidence and ease.

Profit and loss questions require due understanding of the fine differences between terms such as cost price, marked price, selling price, profit percentage, and profit margin. Cost price is the actual expense borne by the seller, while marked price is the amount printed or displayed on the product. Selling price, however, is what the buyer actually pays. Mark up percentage is always calculated on cost price, discounts apply to marked price, and profit comes from the gap between selling price and cost price. A common source of error is mixing up profit percentage and profit margin. The following short video explains the profit and loss concepts, walks through examples, and prepares you to apply it on the GMAT.

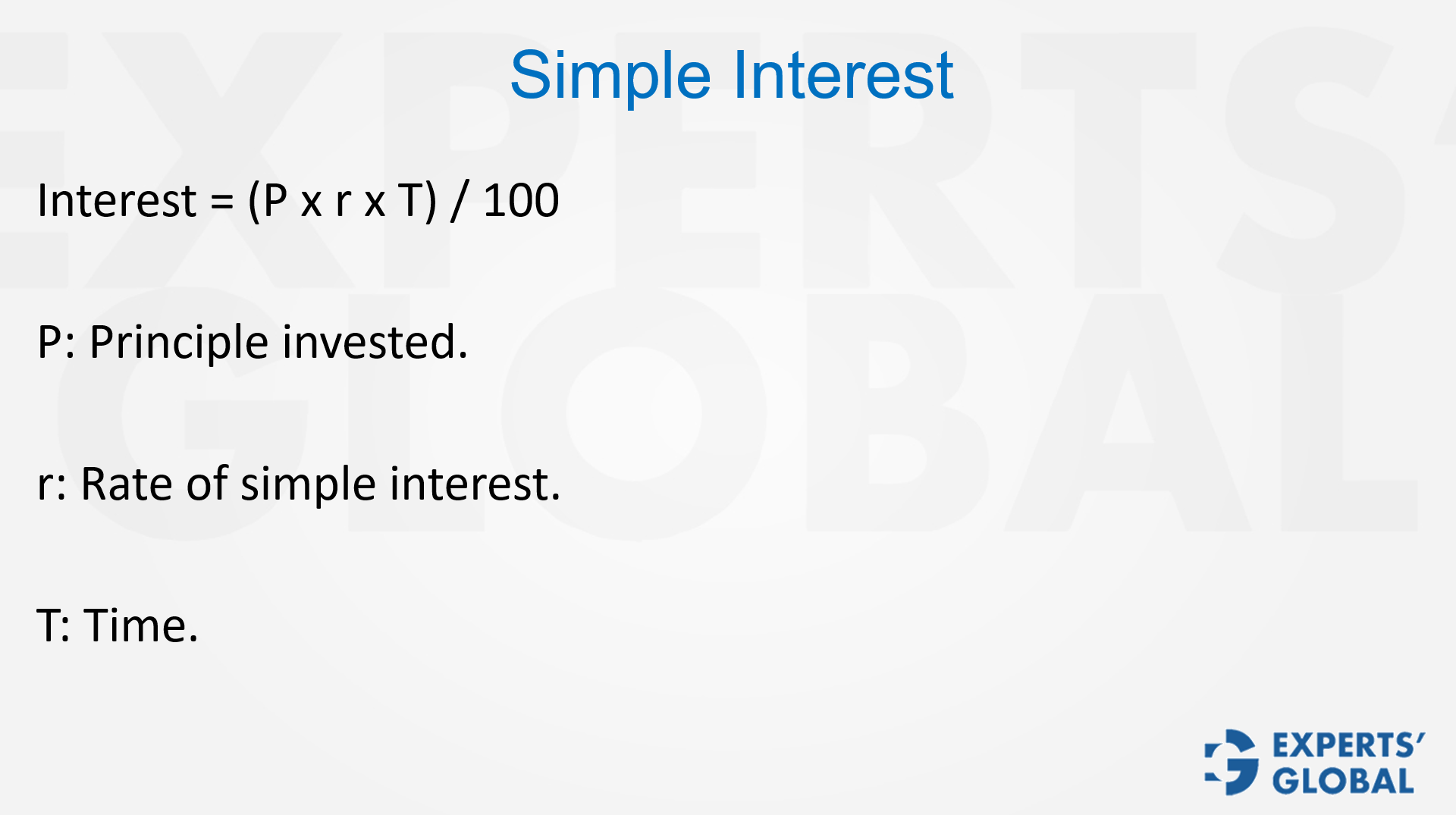

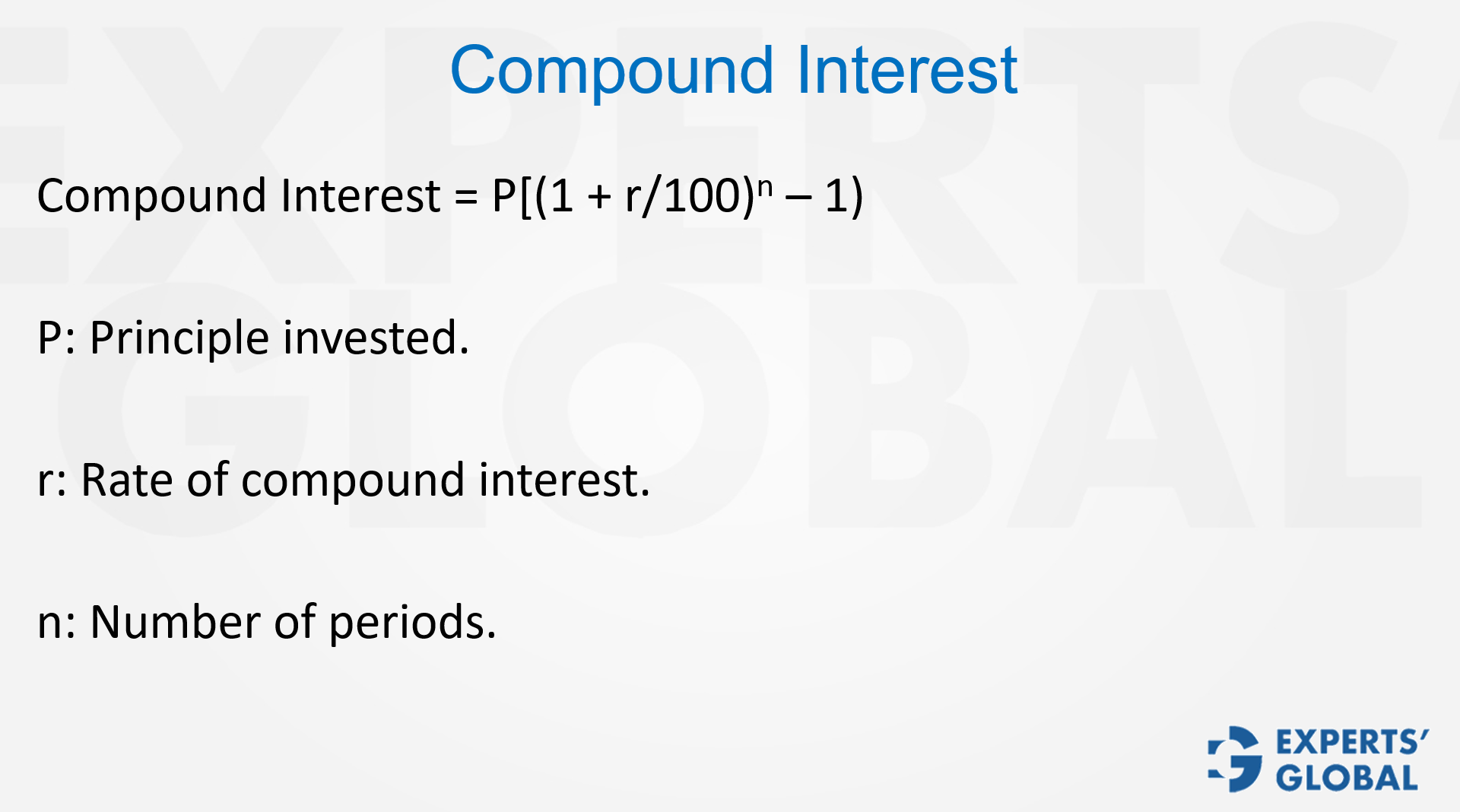

Interest-based problems appear often in aptitude exams, and they assess much more than your comfort with arithmetic. They reflect how clear your concepts are and how well you use them when the clock is ticking. The two central types are simple interest and compound interest. Although both depend on the same basic elements of principal, rate, and time, their calculation methods and final results differ sharply. Simple interest grows in a straight line and follows the formula (P × r × T) / 100. Compound interest grows at an increasing pace and is captured by the expression P[(1 + r/100)ⁿ – 1], where interest is periodically added back to the principal. The real challenge lies not in memorizing these formulas, but in applying them correctly to real situations. Compounding frequency, for instance, can change the outcome significantly, as seen in semi annual or quarterly compounding. The short video that follows offers a clear explanation of this idea and shows how the GMAT may test it.

Mean, or average, gives the central value of a set of numbers, median identifies the middle value when the numbers are arranged in order, and mode highlights the value that occurs most often. Range measures the spread between the highest and lowest values, variance captures how far the numbers sit from the average, and standard deviation expresses this spread in a more interpretable form. These concepts work together to describe data in a clear and structured way, and proper coverage of them is an essential part of a comprehensive GMAT preparation course. This page offers an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

The average, or arithmetic mean, is calculated by dividing the sum of all observations by the total number of observations. While the concept itself is straightforward, it serves as the foundation for some brilliant, intricate, and thought-provoking questions. This engaging video explores the concept in depth, highlighting its applications and demonstrating the most common ways it is tested on the GMAT.

Among the three measures of central tendency, mean, median, and mode, the mode is often the easiest to understand yet the least explored. While the mean reflects balance and the median marks the middle, the mode focuses on repetition. It identifies the value that appears most frequently in a data set. This makes it especially useful when studying test scores, customer choices, or patterns where repeated outcomes matter. For example, in a list of exam scores, the score that occurs most often is the mode. If two or more values share the same highest frequency, the data has multiple modes. This possibility of more than one mode often surprises students, but it is a completely natural situation in quantitative analysis. The short video below presents the concept and gives examples of how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Among the three central measures of data, mean, median, and mode, the median plays a distinct role. While the mean reflects the overall balance of the list, the median identifies the middle value, dividing the data into two equal halves. To find it, first arrange the numbers in order. If there is an odd number of terms, select the single middle value; if there is an even number of terms, take the average of the two central values. In this concise video, you see the concept explained and illustrated through GMAT style testing.

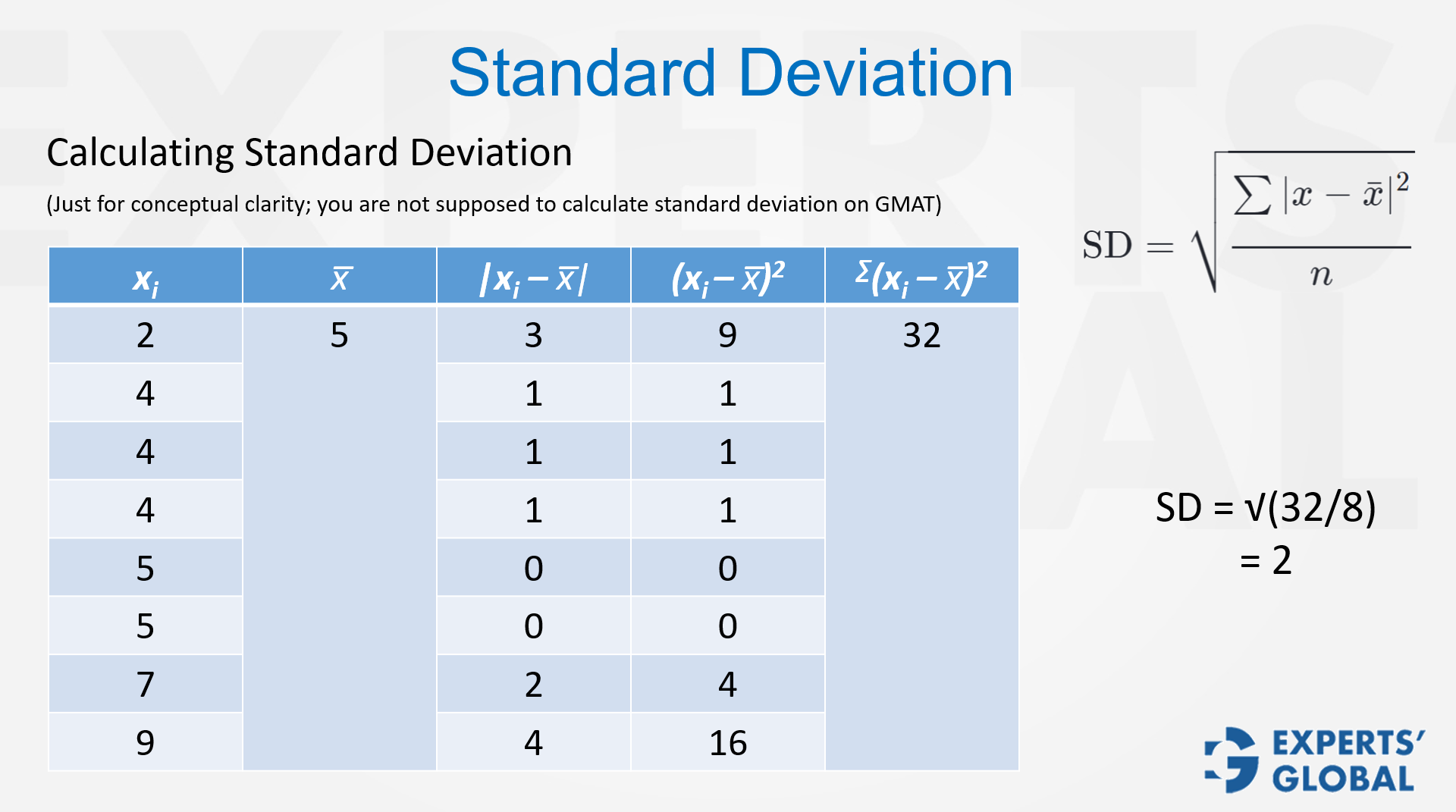

Standard deviation is one of the main measures of variability in statistics, and it often appears in both GMAT Quantitative Reasoning and GMAT Data Insights questions. The GMAT does not ask you to do long, detailed computations to find the standard deviation of a data set, but you must clearly understand how it behaves and how it changes when the data set changes. The exam checks whether you can think about the spread of data, not only work with averages. For example, a set with a higher standard deviation has values that sit farther from the mean, while a lower standard deviation shows that the values stay close together. You also need to be clear on how simple operations, such as adding, subtracting, multiplying, or dividing every element by a constant, affect the standard deviation. The following short video walks through this idea and shows exactly how it may be tested on the GMAT.

Understanding how data is distributed is central to both Quantitative Reasoning and Data Insights on the GMAT. Two of the simplest tools for seeing this spread are range and variance. Range is the most basic measure of variability, showing the gap between the largest and smallest values in a set. Variance, which is the square of the standard deviation, gives a richer picture of how all the values spread across the data set. While range is quick to calculate, variance provides a deeper mathematical sense of diversity. The short video that follows presents this idea in a straightforward way and shows how the GMAT can test it.

Linear equations, or simple equations, describe relationships where variables change at a constant rate, while quadratic equations describe relationships where variables change in a squared or curved pattern. Together, they form a core part of algebra and support many problem-solving situations on the test. This section of the page offers an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

One of the powerful time-saving habits on the GMAT is knowing when to reduce the number of variables in a question. Many students automatically introduce several unknowns for simple relationships, which only stretches the work and raises the chance of slips. A cleaner, faster method is to express everything in terms of a single variable whenever possible. This approach not only keeps calculations lighter but also reduces confusion and keeps the solution well organized. The video below explains this approach step by step, and shows how it works in practice on the GMAT.

Quadratic equations start to feel surprisingly graceful once you see the pattern underneath. On the GMAT, they test how well you recognize structure and break a problem down efficiently. One of the most dependable ways to solve a quadratic equation is factorization, where you split the middle term into two parts whose product matches the product of the first and last coefficients. The following short video introduces this concept gently and shows how it might appear on the GMAT.

Inequalities express relationships where one quantity is greater than, less than, greater than or equal to, or less than or equal to another, often asking you to identify the range of possible values instead of one fixed answer. They appear in many GMAT algebra problems and show up frequently on the exam. This page gives you a well-organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, to help you prepare for this concept efficiently.

Absolute value, or modulus, inequalities show up often on the GMAT. The key idea is that any modulus expression naturally divides into two cases, one positive and one negative. If you miss either case, you quietly miss part of the solution set. The short video below explains the method, walks through it step by step, and helps you apply it on GMAT questions.

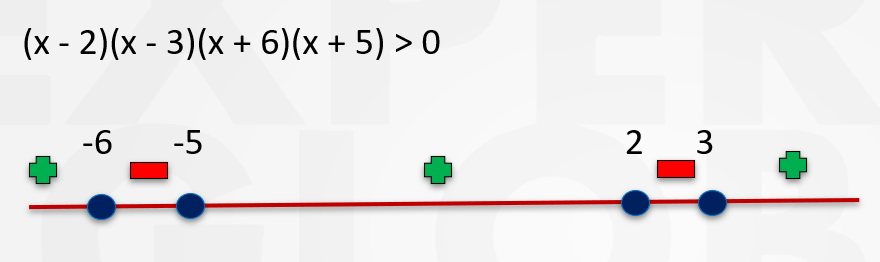

Polynomial inequalities can be feel complex but when approached methodically, are easy to solve. The Wavy Curve Method for solving such inequalities centers on factorization and on observing how the polynomial behaves near its critical points. The short video below explains the concept and shows the typical GMAT question forms.

Knowing how positive and negative numbers behave under multiplication and exponents is one of the simplest yet most powerful ideas in mathematics. In the GMAT Quant section, this understanding becomes essential in inequality questions and number properties problems. One small sign mistake can reverse the entire answer, which makes these questions feel sensitive. The key rules seem easy at first: positive times positive stays positive, negative times negative becomes positive, and so on. However, once exponents and inequalities appear together, the situations become more layered. For example, a negative number raised to an odd power versus an even power produces completely different results, and spotting that difference makes all the impact. This short video lesson explains the concept and shows how the GMAT generally tests it.

Many GMAT questions on inequalities and functions demand a sharp feel for how numbers act in different ranges. Patterns that seem obvious for larger values can flip completely when you test numbers between −1 and 1. For example, you may expect 1/x to get smaller as x increases, but the opposite happens when x lies between 0 and 1. In the same way, squaring a small fraction makes it smaller, while taking its square root makes it larger. Similar reversals occur with negative numbers, where the behavior shifts again. These fine changes sit at the heart of several higher level inequality problems. In the following conceptual video, the idea is explained step by step, along with how it can show up on the GMAT.

Some of the most complex GMAT questions use phrases such as “may be true,” “can be true,” or “must be true.” These are not about routine equation solving. They focus on testing conditions logically, and deciding whether a statement works in at least one situation or whether it holds in every possible case. In may be true or can be true problems, your job is not to prove a rule forever, but to find one example that makes the statement work. If even one case fits, that option is acceptable. In must be true or always true questions, the requirement flips: if you find even one situation where the statement fails, you must eliminate that choice. This following conceptual video explains the idea and shows how GMAT questions often build around it.

Work-rate problems focus on how fast a task gets completed when one or more agents work on it, connecting the amount of work done to the time taken and the speed of each contributor. They help you build a clear sense of how individual or combined effort turns into total output. This page offers you a well-organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

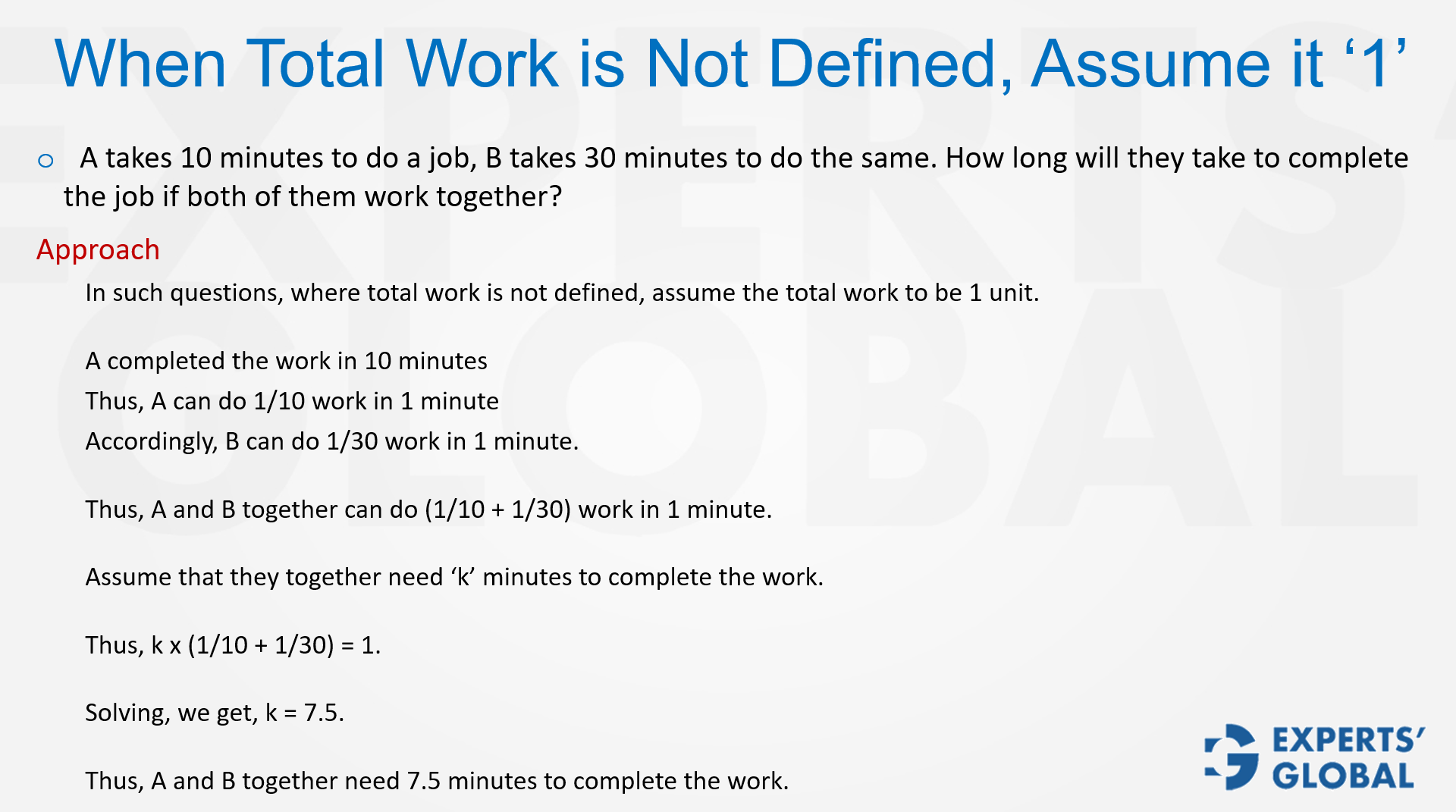

Work and time questions rank among the most classic problem types in aptitude tests, including the GMAT. They are straightforward, but you need a clear, structured method if you want to solve them quickly and correctly. One of the most practical approaches is to treat the entire task as one complete unit, and then find what fraction of that work each person completes in a given time. This short video explains the approach, shows it in action through problems, and helps you apply it on GMAT problems.

Work rate questions test how well you break a situation into simple parts and figure out how long a task takes when multiple people or teams work together. The key move is to express the total work in man-hours or man-days, depending on how the question is set up. This helps you translate the efforts of men, women, or groups with different efficiencies into one common measure. For example, if 10 men working 12 hours a day finish a job in 20 days, the total work equals 10 × 20 × 12 man-hours. Any new mix of workers must match this same total work. The following conceptual video explains this idea clearly and shows how it can be applied on GMAT questions.

Many GMAT work problems include actions that either move the job forward or undo part of it. Treat forward actions as positive work and reversing actions as negative work, then combine these signed rates using one unit, such as jobs per minute or jobs per hour. The following short video explains the idea in simple language and shows how the GMAT can test it.

Time, speed, and distance describe how far something travels, how quickly it moves, and how long the motion lasts. In relative speed questions, they also describe how one body moves compared with another, both when they move in the same direction and when they move in opposite directions. These ideas help you understand motion, pacing, and rate-based scenarios with clarity. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

Average speed always equals total distance divided by total time. When the same distance is traveled at two different speeds, you must not use the plain arithmetic mean. You need to account for the entire trip. Train yourself to rewrite every situation as total distance over total time, whether it involves multiple legs, uphill and downhill stretches, or shifting speeds. In the short video below, the approach is explained step by step, shown through questions, and prepared for use on GMAT problems.

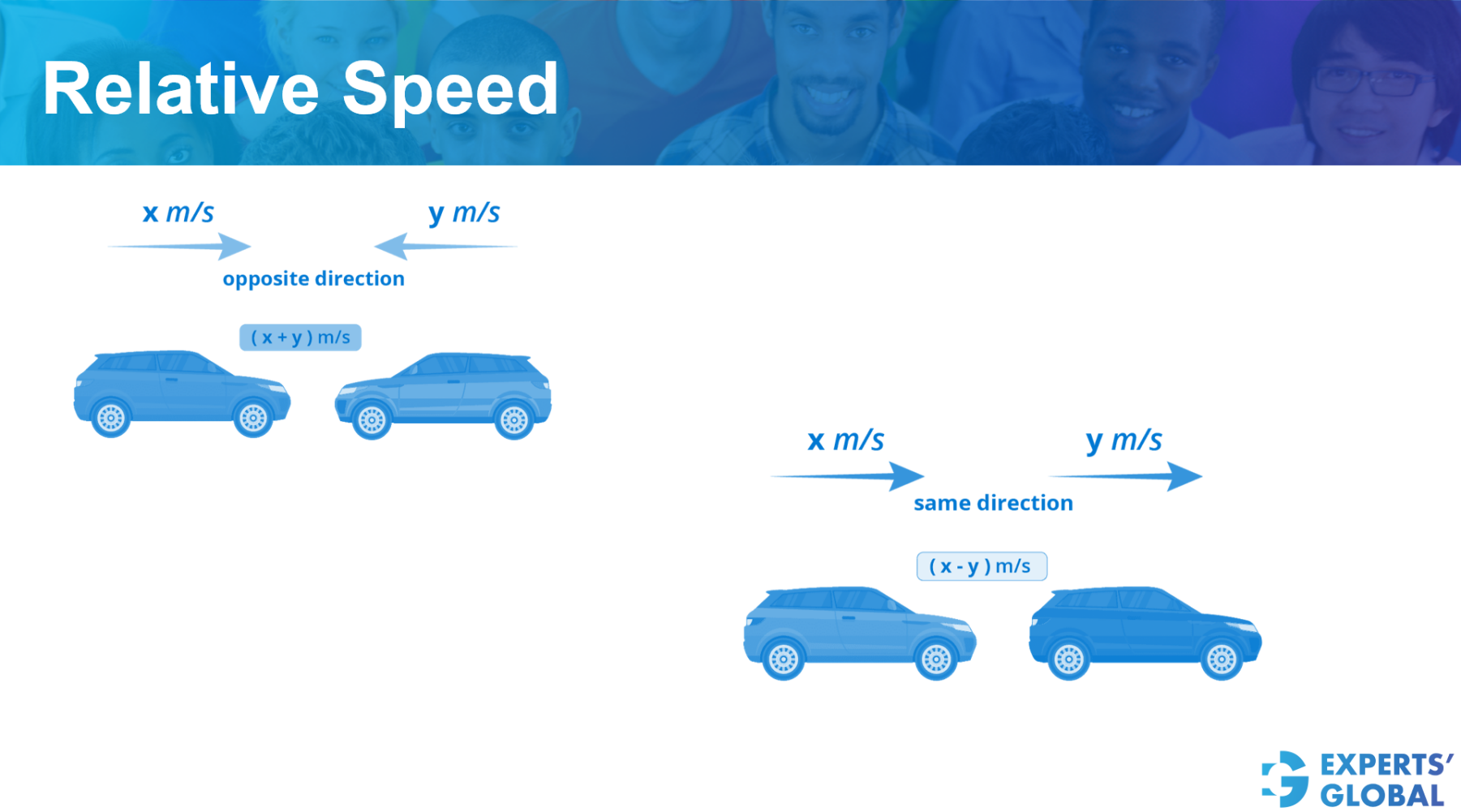

The core idea of relative speed is: when two objects move in opposite directions, their speeds add, and when they move in the same direction, their speeds subtract. This single rule supports many GMAT questions that appear complicated on the surface. The video lesson below makes the concept easy to understand and shows how the GMAT can test it.

Coordinate geometry explains how you represent points, lines, and shapes on a plane using pairs of numbers, so you can study location, distance, and simple geometric patterns through algebra. It blends visual reasoning with numerical thinking in a very approachable way. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

The coordinate axes, also called the xy plane, are one of the most foundational ideas in mathematics, and they sit at the center of many GMAT questions. The axes split the plane into four quadrants, and each quadrant is defined by the signs of x and y. The rule is simple but extremely useful: to the right of the y axis, x is positive, and to the left, x is negative. In the same way, above the x axis, y is positive, and below it, y is negative. The short video below introduces the idea, explains it, demonstrates it, and prepares you to apply it on GMAT.

In coordinate geometry, one essential skill is calculating the distance between two points. It is the straight-line length joining the two points, often called the Euclidean distance. For example, the distance between (2, 3) and (4, 6) is √13, which is the exact length of the line segment connecting them. The short video below explains the concept clearly and shows how it may be tested on the GMAT.

Knowing how to write the equation of a line is a key skill in coordinate geometry, and it supports a wide range of problem solving in your GMAT preparation. A line can be written in different forms depending on the information you have, and comfort with these forms helps you spot patterns in questions quickly. The most common is the slope-intercept form, y = mx + c, where m is the slope and c is the y-intercept. Another useful form is the intercept form, x/a + y/c = 1, where a is the x-intercept and c is the y-intercept, especially helpful when both intercepts are known. Also, when you know a line passes through two points (x₁, y₁) and (x₂, y₂), you can write its equation using the two-point form: (x – x₁)/(x₂ – x₁) = (y – y₁)/(y₂ – y₁). The short video below explains this idea step by step and shows how the GMAT can test it.

Slope sits at the center of understanding straight lines on the coordinate plane. At its core, slope tells you how quickly a line rises or falls as you move from left to right. It is defined as the ratio of the change in the vertical direction (y) to the change in the horizontal direction (x). A slope of zero represents a perfectly horizontal line, a positive slope describes a line that goes upward, and a negative slope describes a line that goes downward. Slope is not just a number. It captures direction, steepness, and overall orientation, which makes it a key tool for reasoning in coordinate geometry. The short video below helps you see the concept with more clarity and shows how the GMAT may test it.

Parallel lines never intersect, no matter how far you extend them, and they always have the same slope. This makes it much easier to find or write equations when one line is already known. Perpendicular lines, on the other hand, meet at right angles, and the product of their slopes equals -1. The short video below explains the idea simply and demonstrates how it appears on the GMAT.

The length of the perpendicular from a point to a line gives the shortest possible distance, and it often unlocks the logic in coordinate geometry based problems. In the same way, knowing how to calculate the perpendicular distance between two parallel lines helps you read spatial relationships with clarity and confidence. Both concepts are precise, systematic, and tested often in aptitude exams. The short video below places the idea in context and shows how the GMAT can test it.

The standard equation of a circle rests on two simple ideas: the center of the circle and its radius. Once you know these, you can write the circle in standard form and use it to decide whether a point lies inside, outside, or exactly on the circle. The short video below walks through the idea and shows how it can be tested in GMAT questions.

Permutations tell you how many ways you can arrange items when order matters, while combinations tell you how many ways you can choose items when order does not matter. Together, they make structured counting feel clear and logical. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation in combinatorics.

When you face counting problems, many students either make simple mistakes or make the task harder by jumping straight to formulas instead of using clear reasoning. Your aim is to think step by step, ask how many choices exist at each stage, and then multiply those choices together. This way of thinking works whether you arrange people in seats, select items, or handle independent events. Consider a simple case. If 10 boys sit in a row of 10 chairs, the first boy has 10 choices, the second has 9, the third has 8, and so on, until the last boy has only 1 choice. This gives 10 factorial, written as 10!, total arrangements. The same idea carries naturally into more complex situations, such as partial arrangements or problems with multiple independent outcomes. The following conceptual video explains the method, shows it solving representative questions, and equips you to apply it on GMAT problems.

The key difference depends on whether the order of arrangement matters. When order matters, you use permutations. When order does not matter, you use combinations. For example, arranging students in a row is a permutations situation because the sequence matters. In contrast, choosing a group of students for a project team is a combinations situation because the order of selection does not matter. The short video below explains the idea in a natural way and shows how it may appear on the GMAT.

Many students feel unsure about when to use permutations and when to use combinations. The formulas can look similar, but the reasoning behind them is quite different. The central step is to check whether order matters. If order matters, you are working with permutations. If order does not matter, it is a combination. To understand this clearly, it helps to think through everyday examples, such as arranging children in a row or selecting a team from a larger group. Each situation follows a clear logic that points you toward using nPr or nCr. The short video below breaks the concept into simple steps, uses examples to clarify it, and shows how the GMAT can test it.

The following concise video demonstrates the application of permutations and combinations formulas through clear examples, explaining how to effectively apply these concepts to GMAT problems.

Permutations and combinations connect closely in counting. A combination focuses on selecting items when the order of selection does not matter, while a permutation builds on that by counting how many different arrangements you can make from the items you selected. Seeing this link matters in GMAT preparation because it shows how one idea naturally leads to the other and why their formulas connect. For example, selecting a group is a combinations situation, and then arranging that same group in different orders becomes a permutations situation. The short video below explains this connection neatly and shows how it can appear on the GMAT.

Permutations and combinations become truly clear when you see them play out across different kinds of situations. One setup can branch into several outcomes, each shaped by its own restrictions or groupings. In the explanatory video that follows, we study eight engaging scenarios that show how results change as the conditions change. Working through these variations is an important part of a focused GMAT preparation course, because it strengthens conceptual understanding and sharpens logical precision. Enjoy solving this interesting set!

Combinations sit at the center of many counting problems because they describe situations where order does not matter. The following explanatory video walks through eight carefully chosen examples that show how small details such as inclusions, exclusions, or minimum requirements can change the final count in meaningful ways. Happy solving!

Circular arrangements are a special type of permutation problem because what matters is how people sit relative to one another, not their exact positions. Unlike seating in a line, moving the entire circle does not create a new arrangement, which is why the number of distinct seatings equals (n − 1)!. In the following explanatory video, we explore several thoughtful variations built on this idea, including cases where certain people sit together, where some must or must not sit next to each other, and how numbered seats change the counting. The conceptual video below guides you through the variations carefully and shows how they can be tested on the GMAT.

Multiset permutations, also called repetitive arrangements, arise when some elements are identical while others are different, which makes the counting more delicate than in basic permutation cases. Instead of treating every item as distinct, you must account for repetition so that you do not overcount. The short video below highlights the idea and shows how it can appear in GMAT problems.

Distributive arrangements in combinatorics focus on how objects get shared among different groups, with the method changing based on whether the items are distinct or identical, and whether any restrictions apply. The following conceptual video explains the concept and equips you to handle this variation on the GMAT.

The following insightful video presents two high-difficulty distributive arrangement problems, offering detailed explanations to help you master this challenging question type. By engaging with these problems and their solutions, you will build the essential skills needed to tackle such questions on the GMAT. As one of the most complex problem types on the exam, mastering these concepts will greatly strengthen your overall quantitative preparation, with a particular focus on combinatorics.

Teaming questions in combinatorics focus on how you form smaller groups from a larger pool, with the real challenge depending on whether the teams count as identical or distinct. When teams are identical in size and status, you need extra care to correct for overcounting. When teams differ in size or carry specific roles, each distinct assignment becomes a separate arrangement. These small shifts demand thoughtful reasoning and show clearly why simple factorials alone do not always produce the correct answer. The conceptual video below makes this idea feel very manageable and shows how it may appear on the GMAT.

Derangements are a special kind of permutation where no element stays in its original position, and they represent an important idea in combinatorics. The following video below deepens your understanding of this concept and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

Probability measures how likely an event is to happen, helping you quantify uncertainty and understand situations that involve chance. It gives you a simple way to compare possible outcomes and judge how likely each one is. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

Logical probability is applied when you determine the required probability through logical reasoning rather than a mathematical formula. In probability, you calculate the number of favorable outcomes divided by the total possible outcomes. When this calculation is done based on logic and reasoning alone, without relying on a formula, it becomes logical probability. The short video below explains the approach, demonstrates how it works, and prepares you to apply it on GMAT.

Probability is the language of uncertainty, giving you a precise way to express how likely events are to occur. On the GMAT, probability questions begin with the simple idea of favourable outcomes over total outcomes, and they often grow into multi-layered situations with several conditions. The accompanying video explains the core ideas through clear, grounded examples, showing how to define the sample space and identify the set of favourable cases.

Independent events are those where one event happening does not change how likely the other event is. In GMAT probability, it helps to think in small, clear blocks. To find the probability that both events happen, handle each event separately and multiply their individual chances. To find the probability that neither happens, multiply their failure probabilities, then use 1 minus that result to get the probability that at least one happens. The same structure also leads to the probability that exactly one event happens, without long case-by-case listing. The video below helps you get a clear handle on this idea and shows how the GMAT may test it.

The complementary method for finding probability involves calculating the probability of the opposite event and subtracting it from 1. For example, if the probability of rain tomorrow is 0.3, the probability of no rain (complementary event) is 1 – 0.3 = 0.7. Complex and intriguing problems can be developed around this concept. The following short video explains the concept and illustrates how it may appear on the GMAT.

On the GMAT, probability often appears through set theory, where overlapping groups and layered conditions require very careful reading. A common mistake is to treat these as simple number problems, when they are really logical puzzles built on Venn diagram thinking. Your real job is to understand the intersections, separate exact categories, and avoid counting the same people more than once. The conceptual video below sharpens this idea and shows how it can be tested in GMAT questions.

Permutation and combination questions in GMAT preparation feel especially rewarding because they show how careful counting connects directly to probability. In P&C-based probability, the numerator stands for the favourable cases and the denominator stands for the total cases. When you first define all possible arrangements and then add the restrictions, each scenario becomes clear. Sometimes the focus is on forming groups, sometimes on avoiding overlaps, and sometimes on using complements, but every variation strengthens your logical thinking. The short video below explains this concept concisely and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

Conditional probability is the probability of an event occurring given that another event has already happened. For example, if there are 10 students in a class and 4 of them like math, the probability that a randomly selected student likes math is 4 out of 10. If you know the student is wearing glasses, and 2 out of the 4 math students wear glasses, the probability changes to 2 out of 4. The following video explains this concept and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

The central idea of areal probability is that probability can be seen as a ratio of areas: the area of the favourable region divided by the area of the entire region. For example, if a dartboard has 100 square units and the red area occupies 25 of those units, the probability of a dart landing on the red area is 25 out of 100. The following video explains this concept and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Functions describe how one quantity depends on another by assigning each input a single, well-defined output, which lets you study patterns, relationships, and changes in a clear, structured way. They create an important bridge between algebraic reasoning and real-world situations. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

Algebraic functions rank among the most central ideas in mathematics, and on the GMAT they carry real depth. At the core, a function is a rule that takes the variable x and replaces it with a specific input. Once the input itself becomes another function, or when you apply functions repeatedly through composition, richer patterns begin to appear. One expression can expand into an entire chain of transformations. It may look complex, but the guiding idea stays the same: substitute the input accurately and simplify with care. Becoming comfortable with this steady, step-by-step substitution gives you the clarity you need even for more advanced questions. In the short video below, the method is explained, shown in action, and applied to GMAT-like examples.

Although the GMAT may feature a wide variety of functions, some are more commonly tested. These include the greatest integer function, the least integer function, and the factorial function, among others. This informative video clearly explains these key GMAT functions and demonstrates how they may appear in the exam.

Two-variable functions involve functions with two inputs, where the output depends on both variables. Nested functions occur when one function is inside another, with the output of the inner function becoming the input for the outer function. The following conceptual video explains these functional clearly and equips you to handle these variations on the GMAT.

Recursive functions are functions where the output of one step is used as the input for the next step. In other words, the function refers to itself in its definition. This type of function often appears on the GMAT. The following video explains recursive functions in a simple way and helps you understand how to tackle them on the exam.

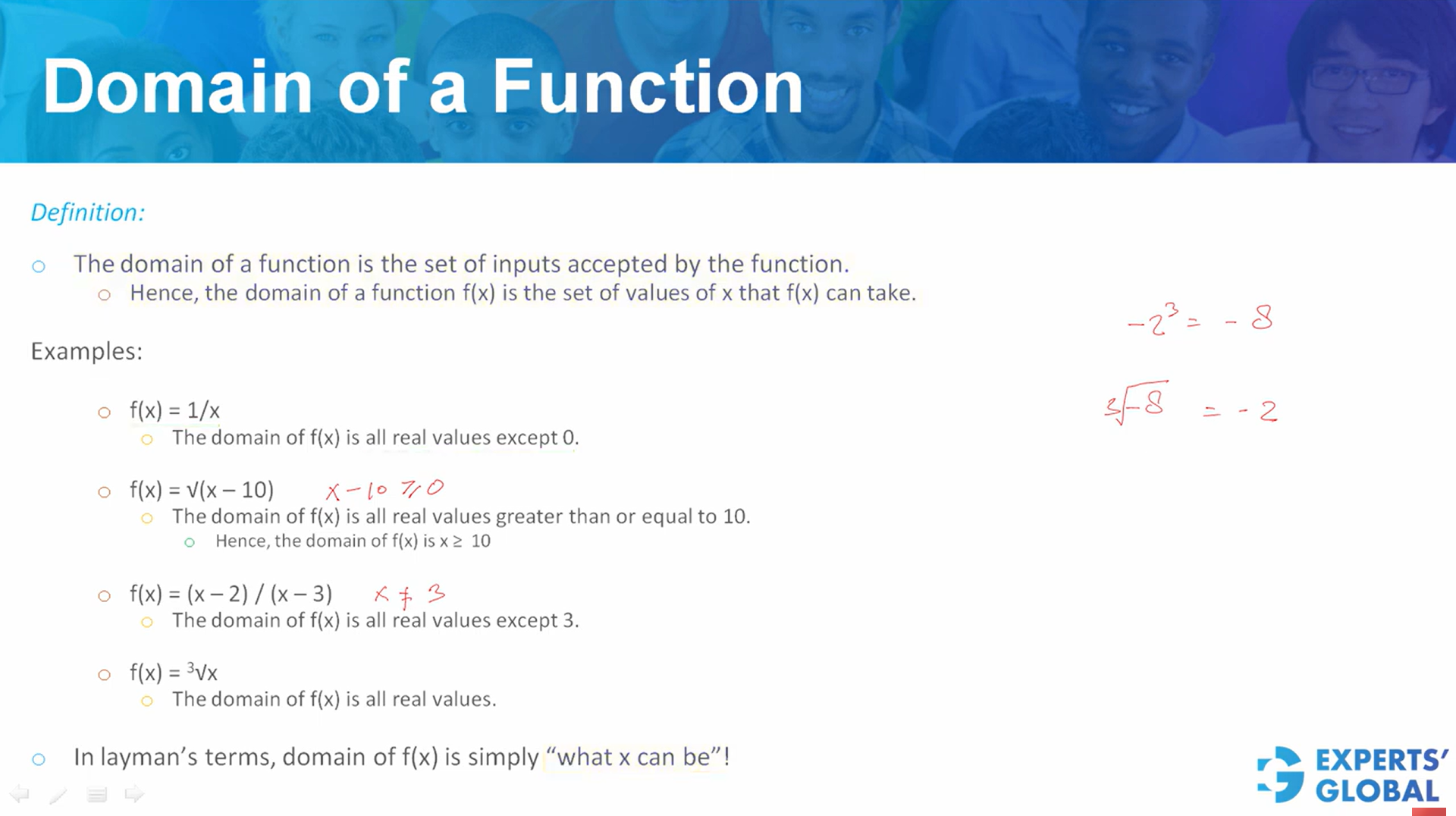

The domain of a function refers to all the possible input values for which the function is defined. In other words, it’s the set of values that you can plug into the function without causing any errors. For example, if f(x) = x², you can plug in any real number, so the domain is all real numbers. If g(x) = 1/x, you cannot divide by zero, so the domain includes every real number except x = 0. The following video explains the domain of a function clearly and helps you understand how to approach related questions on the exam.

Sequences are ordered lists of numbers that follow a clear pattern, while a series is the sum of the terms in such a list. These ideas help you recognize structure, repetition, and growth in a very intuitive way. This page offers you an organized, subtopic-wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

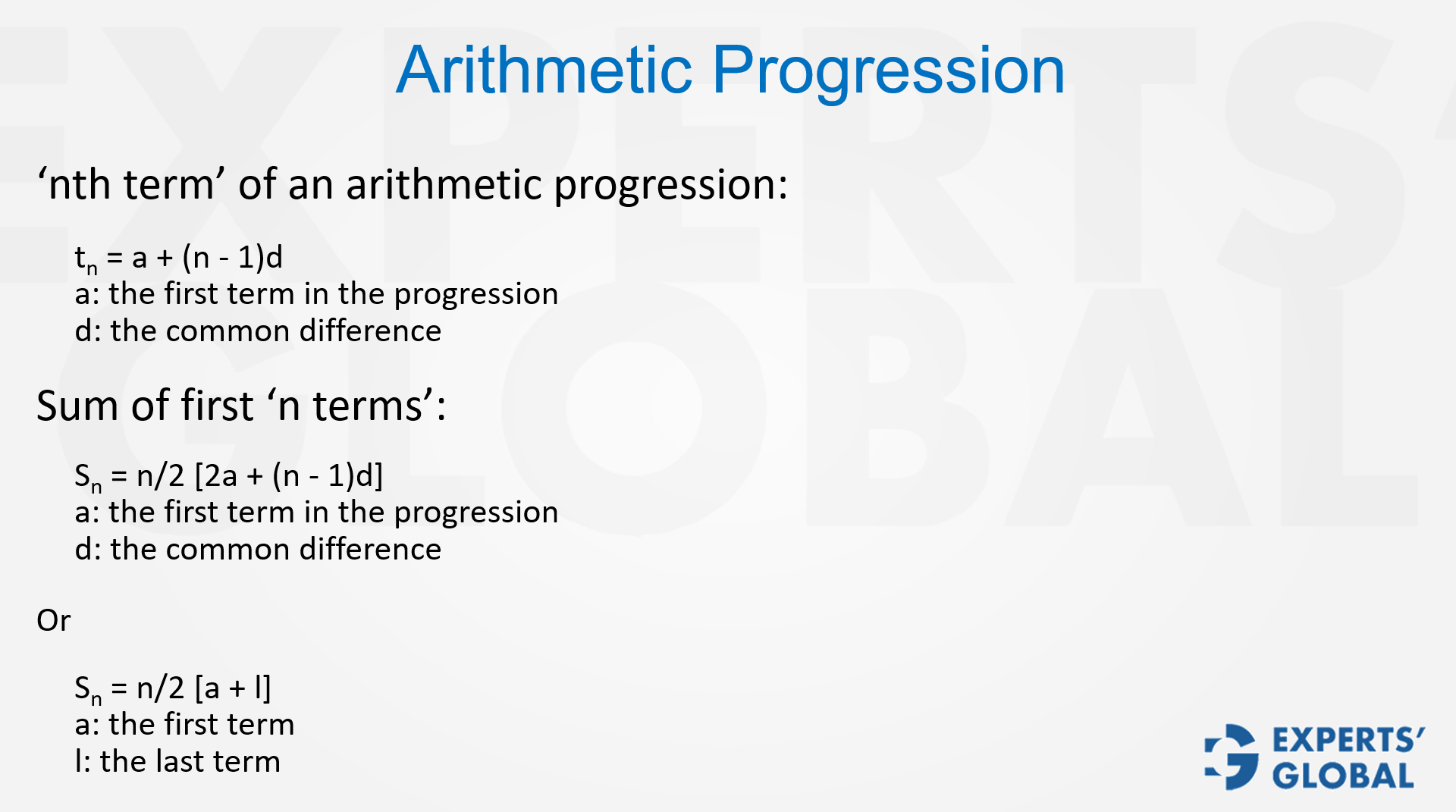

An arithmetic progression is a sequence of numbers where the difference between consecutive terms is constant. For example, 2, 5, 8, 11 has a common difference of 3. The nth term can be found using the formula Tn = a + (n – 1) * d, and the sum of the first n terms is Sn = n/2 * [2a + (n – 1) * d]. The following video explains these concepts and helps you solve related GMAT problems.

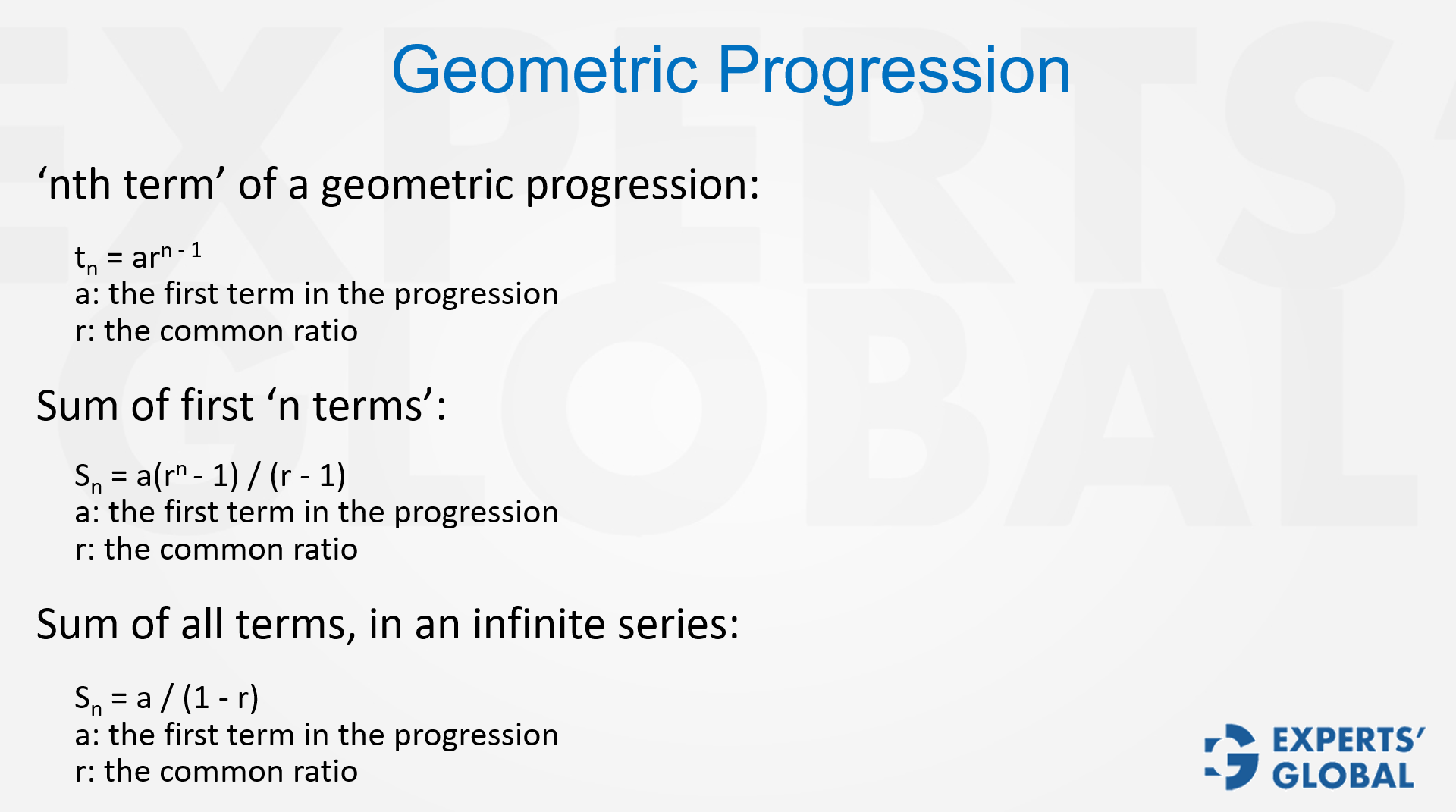

A geometric progression is a sequence of numbers where each term is found by multiplying the previous term by a constant ratio. For example, 3, 6, 12, 24 has a common ratio of 2. The nth term is given by Tn = a * r(n – 1), and the sum of the first n terms is Sn = a * (1 – rn) / (1 – r) for r ≠ 1. For an indefinite geometric progression (when n approaches infinity), the sum is given by S = a / (1 – r), where |r| < 1. The following video explains these concepts and helps you solve related GMAT problems.

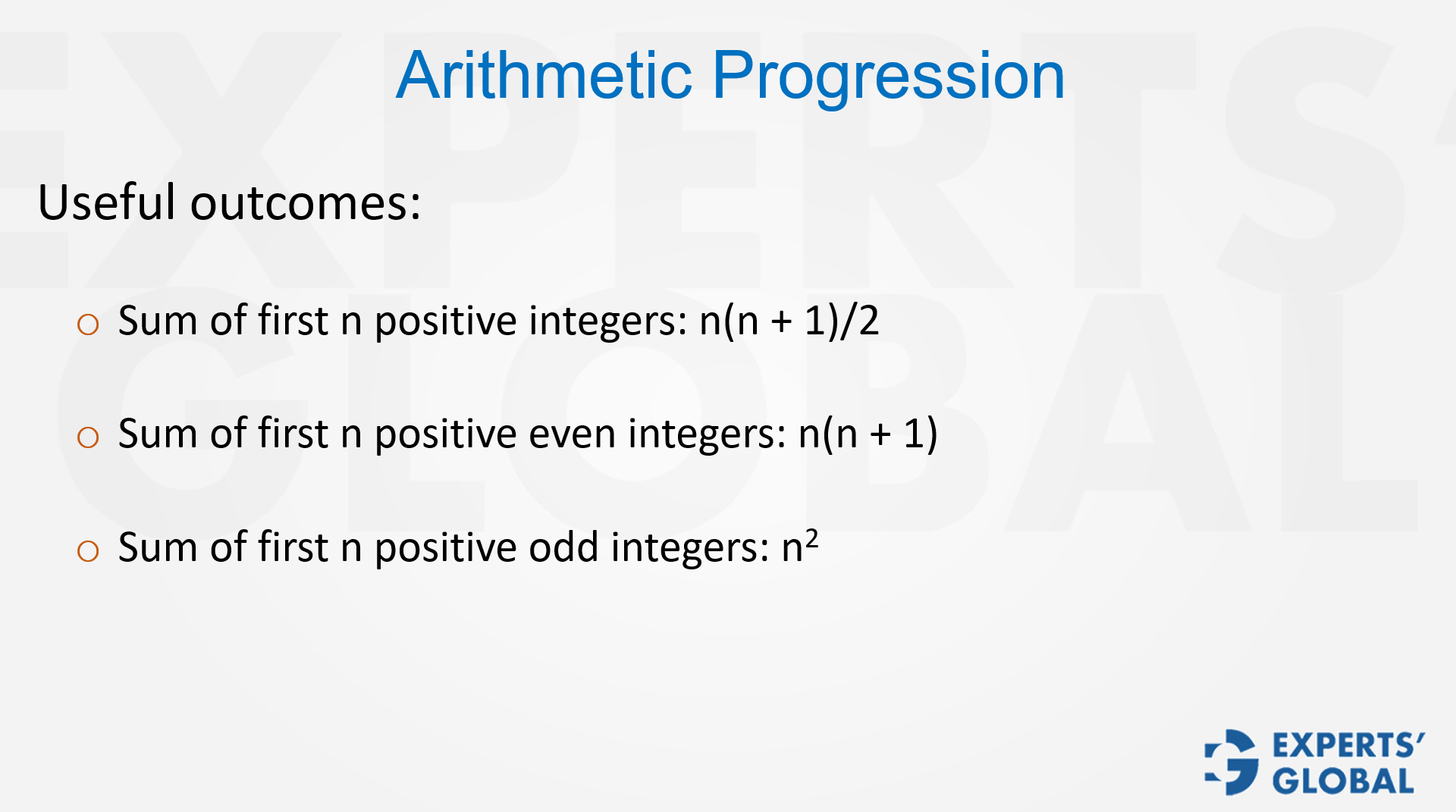

Summation formulas are used to find the sum of a series of numbers. For the sum of the first n integers, the formula is S = n(n + 1) / 2. For the sum of the squares of the first n integers, the formula is S = n(n + 1)(2n + 1) / 6, and for the sum of the cubes, the formula is S = [n(n + 1) / 2]². The following video explains these formulas and helps you solve related GMAT problems.

15 full-length GMAT practice tests (includes a free test)

End-to-end GMAT prep course online (includes 7-day free trial)

GMAT Prep + Admission Consulting Bundle