Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Probability describes the likelihood of an event happening, helping us quantify uncertainty and make sense of situations that involve chance. It provides a simple way to compare possible outcomes and evaluate how likely each one is. A clear understanding of probability is an essential part of any comprehensive GMAT preparation course. This page offers you an organized subtopic wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

Probability questions on the GMAT can look more daunting than they truly are, especially when several cases or overlapping conditions are involved. The heart of the topic lies in spotting patterns, complementary events, and independence, which turn even layered situations into clear, stepwise problems. In this article, together with the supporting video, we use the example of two shooters with different chances of hitting a target to show how scenarios such as both hitting, neither hitting, or exactly one hitting can be handled in a systematic way. The exercise highlights that probability is less about memorizing formulas and more about clean thinking and organized reasoning. Building this discipline is an important part of solid GMAT preparation, as it trains you to approach questions with structure instead of relying on guesswork. The short video that follows clarifies the approach, demonstrates its use, and prepares you to carry it into GMAT drills, sectional tests, and full-length GMAT simulations.

Probability is the language of uncertainty, offering a precise framework to express how likely events are to occur. On the GMAT, probability questions grow from the basic idea of favourable outcomes over total outcomes and often expand into multi layered situations with several conditions. This article and the accompanying video walk through the core ideas using clear, grounded examples, showing how to define the sample space and identify the set of favourable cases. Once this discipline is in place, even problems that appear complicated at first sight break down into simple, ordered steps. Developing such clarity should be a natural part of every GMAT preparation journey, because strengthening logical thinking and systematic reasoning lies at the heart of strong performance. The brief video that follows walks you gently through this idea and illustrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Independent events are those where the occurrence of one does not affect the likelihood of the other. In GMAT probability, it helps to think in small, clear blocks. For the probability that both events occur, treat each one separately and multiply their individual chances. For the probability that neither occurs, multiply their failure probabilities, and then use 1 minus this value to find the chance that at least one happens. The same structure leads to the probability of exactly one event occurring, without the need for long case-by-case listing. Before you start calculating, always check whether independence is mentioned; if it is not stated, do not assume it. During your GMAT preparation, keep practicing how to convert short verbal statements into neat algebraic expressions. The short video below gives you a clear handle on this idea and shows how the GMAT may test it.

Probability often becomes more approachable when you lean on clear logic instead of brute force. Imagine a dartboard question where the chance of hitting the bullseye in a single throw is one half, and you are asked how many throws are needed to push the probability of at least one bullseye above 90%. A common misstep is to start listing every possible outcome over multiple throws, which quickly becomes messy. A cleaner method is to first find the probability of missing the bullseye every time, and then subtract that value from one to get the chance of hitting it at least once. This approach is not only quicker but also easier to extend to a larger number of attempts. Such clarity in reasoning is vital on the GMAT, where efficiency under time pressure matters greatly. The following short video simplifies this concept and demonstrates how it can show up on the GMAT.

Probability on the GMAT often appears through set theory questions, where overlapping groups and layered conditions must be read very carefully. A frequent mistake is to treat these as mere number problems, when in truth they are logical puzzles shaped by Venn diagram ideas. Your real task is to see through the intersections, separate exact categories, and avoid counting the same people more than once. For example, a question may ask about those who belong to exactly two sets, or those who do not belong to any. The challenge is to break the information into clear regions and then identify the favourable cases against the overall total. The brief video that follows brings this idea into focus and shows how it can be tested in GMAT questions.

Permutation and combination questions in GMAT preparation are especially rewarding because they show how careful counting connects directly to probability. In P&C based probability, the numerator represents the favourable cases and the denominator represents the total cases. When you first define all possible arrangements and then layer on the restrictions, each scenario becomes transparent. At times the focus is on forming groups, at other times on avoiding overlaps, and sometimes on using complements, but every such variation strengthens your logical thinking. The short video below covers this concept in a concise way and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

Conditional probability is one of the most engaging and practically useful ideas in mathematics. The key change is that the sample space is no longer the full set of outcomes, but only those that satisfy a stated condition. This narrowing of the universe affects both the denominator and the way we count favourable cases. On the GMAT, this concept is used to test not just familiarity with formulas but also sharpness of thinking. The real challenge is to read the condition carefully, reshape the sample space accordingly, and only then begin the calculation. You will see this approach in card problems, dice questions, and word based scenarios where the condition is quietly woven into the language. The following short video explains this idea with care and demonstrates how it may appear on the GMAT.

Areal probability is one of the most natural ways to think about probability, because it links an abstract idea to simple geometric pictures. The central thought is that probability can be viewed as a ratio of areas: the area of the favourable region divided by the area of the entire region. GMAT questions that use this idea may draw on basic geometry or coordinate geometry, where a condition such as a point lying within a triangle or x being greater than y defines the favourable zone. The real task is not heavy computation but a clear mental picture of the figure and an accurate sense of the boundaries. Once that is in place, the required probability becomes a comparison of areas that can often be found with straightforward mathematics. The brief video that follows lays this concept out clearly and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

This segment brings together a set of GMAT-style Probability questions, each supported by a thorough, stepwise explanation. Work through every item slowly and thoughtfully, drawing on the methods and ideas you have just studied on this page for solving Probability questions on the GMAT. At this point, give priority to applying the reasoning framework in a precise and disciplined way rather than only aiming for a correct answer. After you complete each question, use the explanation toggle to reveal the official answer and to read the full, descriptive solution.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

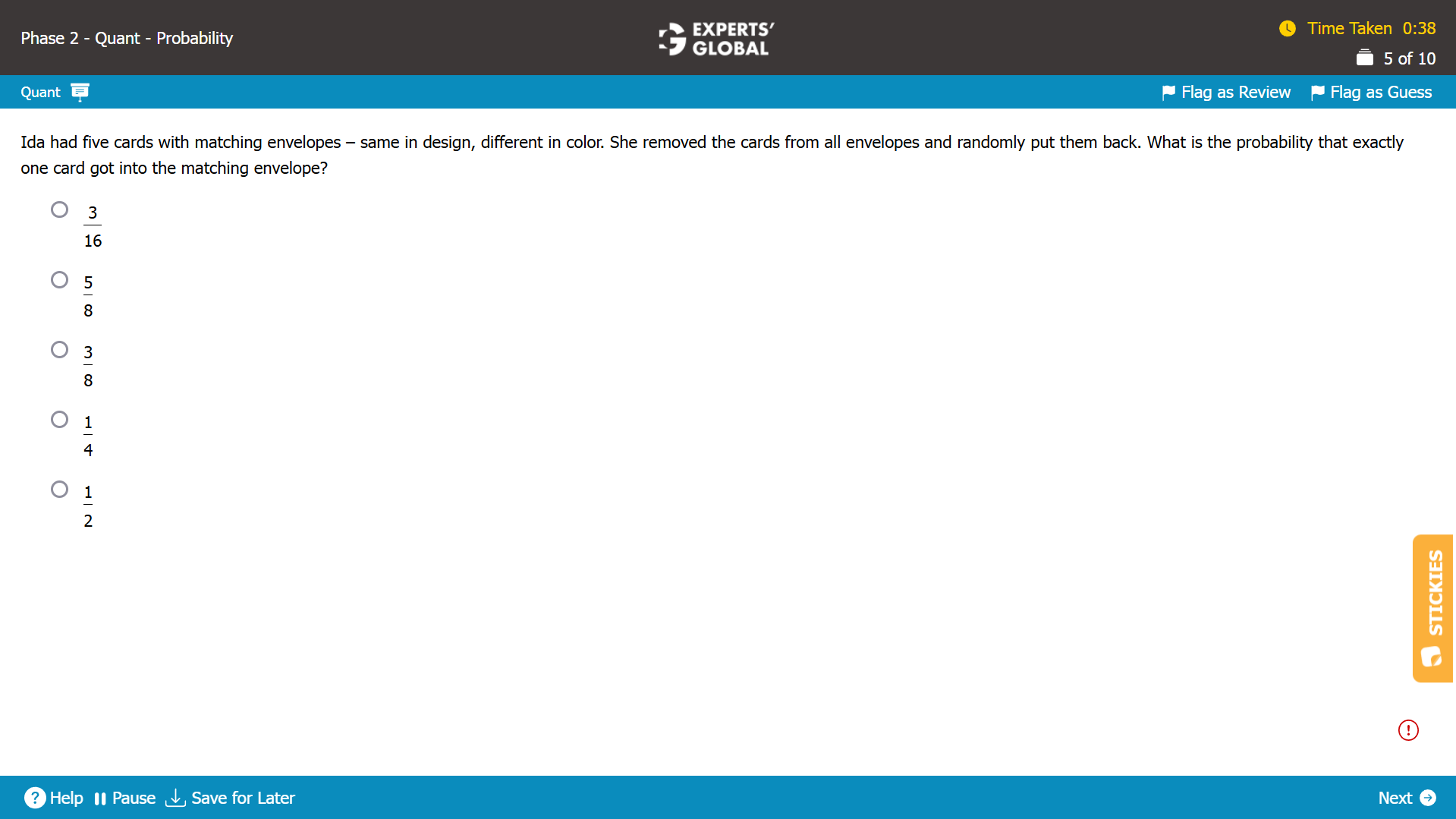

Among 5 combinations of card and envelop, there are 5 ways in which one card goes in the correct envelope.

Among the other 4 cards, none goes in the correct envelope.

So, number of derangements of 4 cards = 4! X (1 – 1/1! + 1/2! – 1/3! + 1/4!) = 9.

Number of cases in which exactly one card got into the matching envelope = 5 X 9 = 45

Total number of cases of 5 cards going in 5 envelopes = 5!

Probability of exactly one card going into the matching envelope = 45 / 5! = 3 / 8.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

The probability that event A will occur = p

The probability that event B will occur = p

The probability that neither event will occur = (1 – p) × (1 – p) = (1 – p)2

The probability that at least one of these events will occur = 1 – The probability that neither event will occur = 1 – (1 – p)2

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

For the product of two integers to be even, at least one of them has to be even.

So, we need to find the probability that, from the two integers that were picked up for multiplication, at least one integer was even.

Probability (at least one integer was even) = 1 – probability (no integer was even) = 1 – probability (both integers were odd)

Number of odd integers in the set = 4

Number of ways in which 2 odd integers can be picked = 4C2 = 6.

Number of integers in the set = 10

Number of ways in which 2 integers can be picked from the set = 10C2= 45.

So, probability (both integers were odd) = 6 / 45 = 2 / 15.

Overall, the probability (at least one integer was even) = 1 – probability (both integers were odd) = 1 – (2 / 15) = 13 / 15.

The probability that the product was even is 13 / 15.

E is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

f(x) = x2 – 7x – 18.

Let’s find the value of x where f(x) = 0.

x2 – 7x – 18 = 0

(x – 9) (x + 2) = 18

x = 9 or x = –2.

x belongs to the range 0 to 15, both inclusive. So, x cannot be –2.

x = 9.

For any value of x lower than x = 9, f(x) will be negative. So, f(x) will be negative for {0, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8}, or for 9 integers.

The value of x can be any integer between 0 and 15, both inclusive.

So, there are 16 possible values of x.

Probability of f(x) being negative = 9 / 16.

A is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

Let’s consider an arrangement in which everybody in the five couples is sitting adjacent to their partners.

Relative to the first couple in a circular table, number of ways in which five couples can sit = (5 – 1)! = 24 ways.

The two individuals in a couple can sit in 2 different orders: husband-wife or wife-husband.

Number of ways in which the two individuals in a couple can sit adjacent to each other = 2.

The same applies to all five couples.

So, total number of required arrangements = number of ways in which five couples can sit X (number of ways in which the two individuals in a couple can sit adjacent to each other)5

Total number of required arrangements = 24 X (2)5 = 24 X 32 = 768.

Total number of arrangements in which 10 persons sit around a circular table without any restriction = (10 – 1)! = 9!

Probability that everybody in the five couples sits adjacent to his or her partner = 768 / 9!

E is the correct answer choice.

High quality Probability questions are not available in large numbers. Among the limited, genuinely strong sources are the official practice materials released by GMAC and the Experts’ Global GMAT course. Within the Experts’ Global GMAT online preparation course, every Probability problem appears on an exact GMAT like user interface that includes all the real exam tools and features. You work through more than 75 Probability questions in quizzes and also take 15 full-length GMAT mock tests that include several Probability questions in roughly the same spread and proportion in which they appear on the actual GMAT.

All the best!