Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Number properties, or number systems, form the foundation of the quantitative section of standardized examinations such as the GMAT. Virtually half of the questions in quant are directly or indirectly built on number properties. When you are comfortable with numbers, you perform better not only across all quantitative section questions but also on the quant-based items in the data insights section. This comfort with numbers also makes your comprehension and computation quicker and sharper, and that improvement is visible in your overall performance on the GMAT. Number properties should therefore be among the very first topics you master in your GMAT preparation course, because they give you a solid grounding and a strong base for your preparation. At the same time, the topic is very interesting and relatively simple to start with, and it prepares you well for the concepts that follow in your study plan.

On the GMAT, every number you see is a real number, so you never work with complex numbers. These real numbers fall into two broad groups, rational and irrational. Rational numbers are those that can be written in the form P/Q, where P and Q are integers and Q is not zero. Irrational numbers, in contrast, can never be written in such a fractional form. From this point, rational numbers break down further into fractions and integers, and integers can be categorized as even or odd, prime or non-prime. Keeping these classifications clear in your mind helps you avoid mistakes on test day. The following video walks through the classification of numbers in a very simple, intuitive way within just a few minutes. Duly understand this basic classification as it will be handy in several problems you will come across in your GMAT drills, full-length GMAT mock tests, as well as the actual GMAT.

Some of the most familiar numbers in the GMAT quant section come with special cases that frequently puzzle test takers. The numbers 0, 1, and 2 look completely ordinary, yet each carries a specific status that can decide the result of a question. The number 0 is an even integer, although many students mistakenly think otherwise. The number 1 is not a prime, even though it is often treated as one. The number 2 is special because it is the only even prime number. These may feel like small points, but on the GMAT, such details can become turning points. The following short video explains these exceptions in a clear manner and shows how they can be tested on the GMAT.

On the GMAT, some of the simplest ideas often hide the most subtle traps. Consider the rules of even and odd numbers. They appear basic, almost too straightforward to deserve attention, yet when used skilfully in GMAT questions, they reveal layers that many test takers miss. The following video helps you understand this concept clearly and highlights the potential pitfalls within this extremely simple yet very engaging concept.

In GMAT Quant, some questions appear time-consuming at first glance. A long string of numbers being multiplied can seem impossible to handle. The usual reaction is to start expanding every term, and that is exactly where many students lose valuable time. In reality, you almost never need to carry out the full multiplication. What truly matters is the units digit. By paying attention only to the last digits of the numbers, you can predict how the product will end without touching the rest. This small change in approach saves time and also supports accuracy in the exam. Simple pattern awareness, such as noticing a 2 and a 5 together, immediately tells you that the final digit of the product must be 0. Developing this kind of number sense is what separates the steady, prepared test taker from the one who feels overwhelmed. The following short video presents this idea in a clear way and illustrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Last digit questions are among GMAT’s favorite types, and you must grow fully comfortable with them as your GMAT prep progresses. Some GMAT Quant problems are built to overwhelm you with their sheer size. A long product of large numbers can make it seem impossible to compute within the test’s time limits. Yet the GMAT does not expect you to multiply everything. It rewards keen observation and thoughtful shortcuts. When you are asked for the last two digits of a huge product, you do not need to expand all the numbers. The key is to track only the final two digits of each factor and notice the patterns that emerge.

At first sight, questions that ask for the last digit of a large power can seem almost impossible. Numbers such as 28729 may look overwhelming, yet the GMAT, of course, never expects you to work out the full value. What truly matters is your ability to break the task into calm, logical steps. The approach relies on two central ideas. First, only the units digit of the base is important. Second, units digits always repeat in cycles of four powers, so dividing the exponent by 4 becomes the real shortcut. Once you have the remainder, you simply raise the last digit to that power to find the answer. Even special situations, such as a remainder of 0 or a negative result after subtraction, can be handled easily when your concepts are clear. With steady practice, this style of reasoning begins to feel natural. The following video illustrates this concept in a simple manner and takes up some worked, GMAT-like examples…

As you prepare for the GMAT, mastering factor based questions is an important step in building real confidence. Instead of listing factors one by one, which is slow and invites mistakes, a wiser method is to rely on prime factorization. By expressing a number as a product of prime factors, adjusting the exponents, and then combining the results, you can find the total number of factors with both speed and accuracy. You need to ensure unique prime bases, add 1 to the power of each prime base, and multiple to get the number of factors. The following video explains this concept in a simple manner and takes up some worked problems…

As you prepare for the GMAT, getting comfortable with factorials reveals some beautiful number patterns. One particularly elegant use is determining the highest power of a given divisor contained within a factorial. Instead of worrying about the whole number, you break the divisor into its prime factors and count how many times each appears. With a bit of practice, this approach feels natural, fast, and very dependable. The brief video that follows sums up this concept clearly and illustrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

During your GMAT preparation, you will notice that the simplest concepts often have the deepest impact. Terminating fractions are a clear example of this. What may look like routine calculation begins to reveal rich patterns when you slow down and observe carefully. Deciding whether a fraction terminates or repeats is less about long computation and more about clear thinking. A decimal terminates when its denominator has no prime factor other than 2 and 5; else, it repeats. The following short video expresses this idea in a simple way and takes GMAT-like worked problems.

Understanding divisibility rules is key to improving both speed and accuracy, particularly for remainder questions on the GMAT. In this brief and engaging video, we cover the fundamental divisibility rules, show how to apply them effectively, and explain how these concepts appear on the GMAT.

As you move through your GMAT preparation, remainder problems offer a beautiful glimpse into how simple ideas can tame large expressions. Instead of carrying out heavy multiplication, you only need to follow the remainders and combine them thoughtfully. This way of working saves time, improves accuracy, and sharpens logical clarity. The short video below offers a simple walk-through of this concept and shows how it may be tested on the GMAT.

In these questions, the aim is to find the remainder of a large power both quickly and correctly. In your GMAT preparation course, you follow a clear routine. First, reduce the base by the divisor. Then try small powers of this reduced base until one produces a remainder of +1 or −1, and treat that exponent as the cycle length. Next, shrink the original exponent using this cycle and replace the big power with 1 or −1. If the result is −1, add the divisor to turn the remainder positive. For any extra factors, repeat the reduce and shrink steps. This keeps the numbers small and avoids heavy multiplication. The following short video shares a clear take on this concept and demonstrates how it is tested on the GMAT.

In your GMAT preparation, a very powerful habit is to write numbers in a neat, structured way. Remainder questions become simpler when you express a number as N = d × q + r and then observe how this form behaves as the divisor changes. This article focuses on a pattern the GMAT particularly likes: you are told that N leaves remainder r when divided by d, and you must find the remainder when N is divided by a factor or a multiple of d. We will reduce the large expression, cancel what vanishes, and track the smaller remainder carefully, step by step. The goal is clarity of thought, not heavy calculation. The short video below captures the essence of this concept and demonstrates how it can show up on the GMAT. The following brief video helps you feel at ease with this idea and shows how the GMAT can test it.

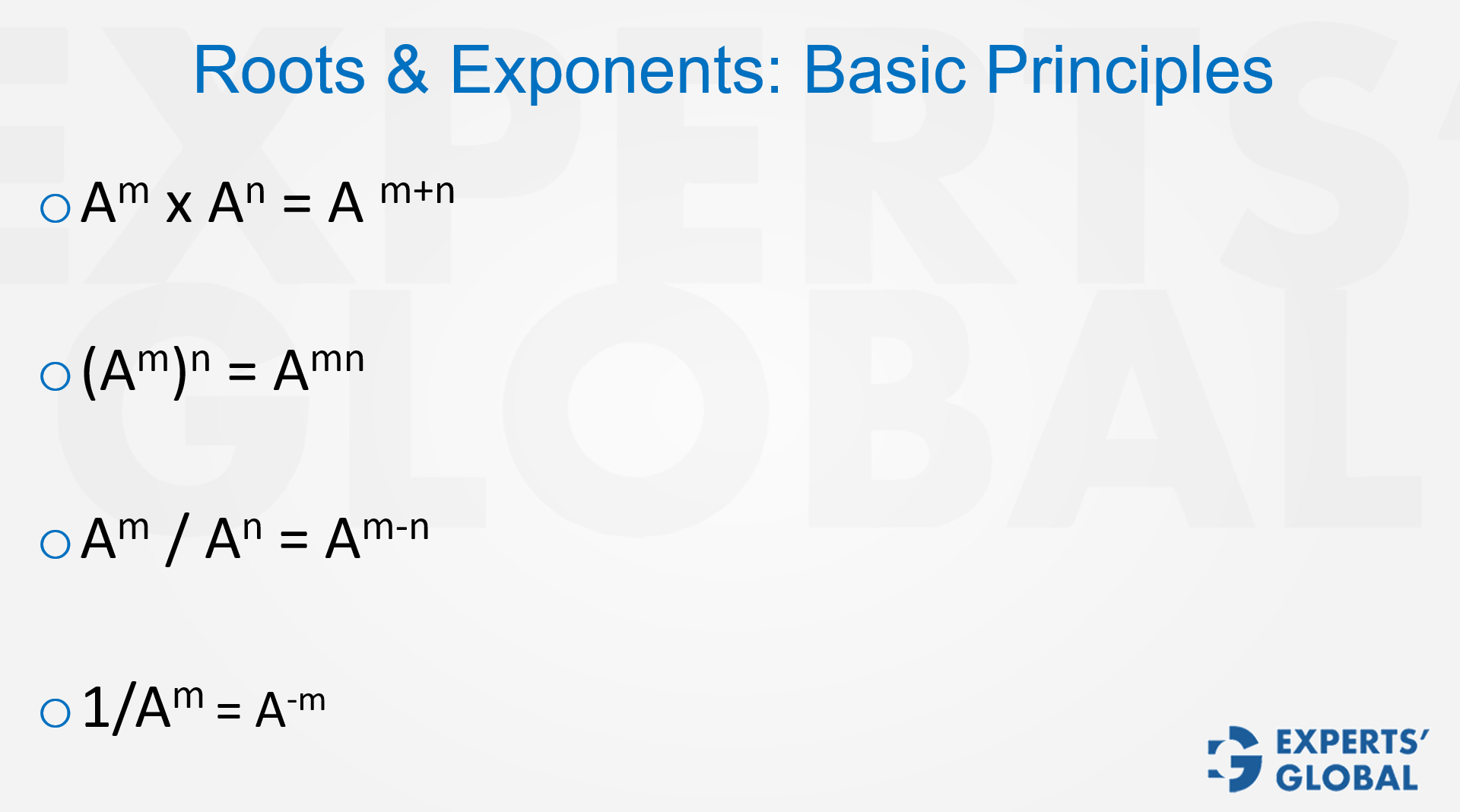

Roots and indices, also referred to as surds and indices, deal with expressing numbers as powers and their corresponding roots, such as square roots, cube roots, and higher order radicals. The following slide brings together the basic principles that govern roots and exponents. These rules work best when the bases of the terms involved are the same, and, in many questions, choosing or recognizing a prime base is especially helpful. Take a moment to brush up these principles, because they will be very useful when you solve higher difficulty GMAT questions involving roots, exponents, surds, and indices. A clear command of these basics will make advanced problems feel more structured and far easier to handle.

Looking for prompt GMAT prep? Check out our GMAT crash course

In your GMAT preparation, you will rely on a steady, trustworthy approach to exponents and roots: rewrite each expression as a power of the same prime base. Turn roots into fractional exponents, merge like powers, align the bases, and then set the exponents equal to solve for the variable. When coefficients show up, factor them out or express them in the same base whenever possible; if that is not convenient, move them carefully to the other side while keeping the bases matched. Always check that the domain makes sense and that you have not slipped in any extra, invalid steps. Through repeated, timed practice across GMAT diagnostic tests, you learn to recognize the base quickly, choose the right transformation, and avoid unnecessary calculation. The brief video below introduces this concept gently and illustrates how the GMAT may test it.

One of the GMAT’s favorite ways to check higher order thinking is by giving you intimidating expressions with very large powers. At first glance, these questions can seem slow and tiring, but the real move is to pause and search for what can be cancelled. The exam is not checking whether you can handle huge calculations; it is measuring how clearly you can see simplifications. Whenever you notice very high exponents in both the numerator and the denominator, the problem is often built so that the largest power can be factored out and removed. What first appears heavy then shrinks into something small and friendly. The short video below reinforces this idea and shows how it can appear in GMAT questions.

On the GMAT, rationalization means removing square roots from denominators by multiplying the top and bottom by a conjugate, which changes (a + √b) to (a − √b) and produces an equivalent fraction without radicals in the denominator. For instance, 1 ÷ (2 + √3) becomes 2 − √3 after multiplying numerator and denominator by (2 − √3). In this lesson, you see how rationalization turns awkward expressions with square roots in the denominator into cleaner, integer based forms, reveals useful structure, and supports calm, systematic manipulation of radicals that strengthens your overall algebra on the GMAT.

In this section, you will work with a curated set of genuine GMAT-style Number Properties questions, each paired with a clear, stepwise explanation. Move through the questions calmly and use the methods and ideas that you have just studied on this page for solving Number Properties questions on the GMAT. At this stage, give more importance to applying the strategy accurately than to simply arriving at the correct answer. After you complete each question, use the explanation toggle to view the correct response and to study the full reasoning behind it.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

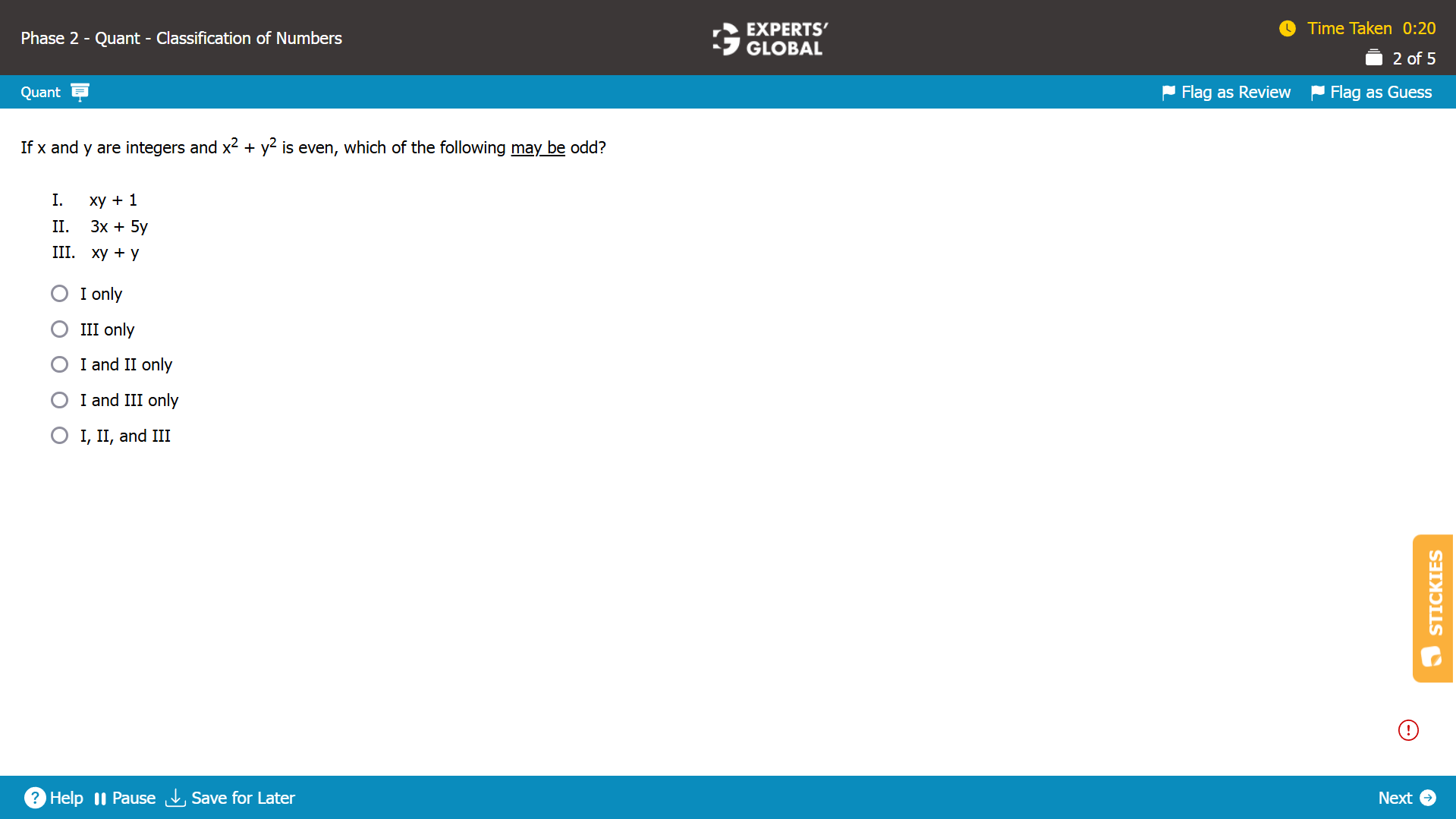

x2 + y2 is even.

There are the following two possibilities.

Possibility 1: x is even and y is even.

For example, x = 2 and y = 4; x2 + y2 = 4 + 16 = 20 is even.

Possibility 2: x is odd and y is odd.

For example, x = 3 and y = 5; x2 + y2 = 9 + 25 = 34 is even.

Let’s determine the even-odd status of (xy + 1).

In Possibility 1…

xy + 1 = (2 X 4) + 1 = 9 is odd.

In Possibility 2…

xy + 1 = (3 X 5) + 1 = 16 is even.

(xy + 1) may be odd.

Let’s determine the even-odd status of (3x + 5y).

In Possibility 1…

3x + 5y = (3 X 2) + (5 X 4) = 26 is even.

In Possibility 2…

3x + 5y = (3 X 3) + (5 X 5) = 34 is even.

(3x + 5y) cannot be odd.

Let’s determine the even-odd status of (xy + y).

In Possibility 1…

xy + y = (2 X 4) + 4 = 12 is even.

In Possibility 2…

xy + y = (3 X 5) + 5 = 20 is even.

(xy + y) cannot be odd.

The only function that may be odd is (xy + 1).

A is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

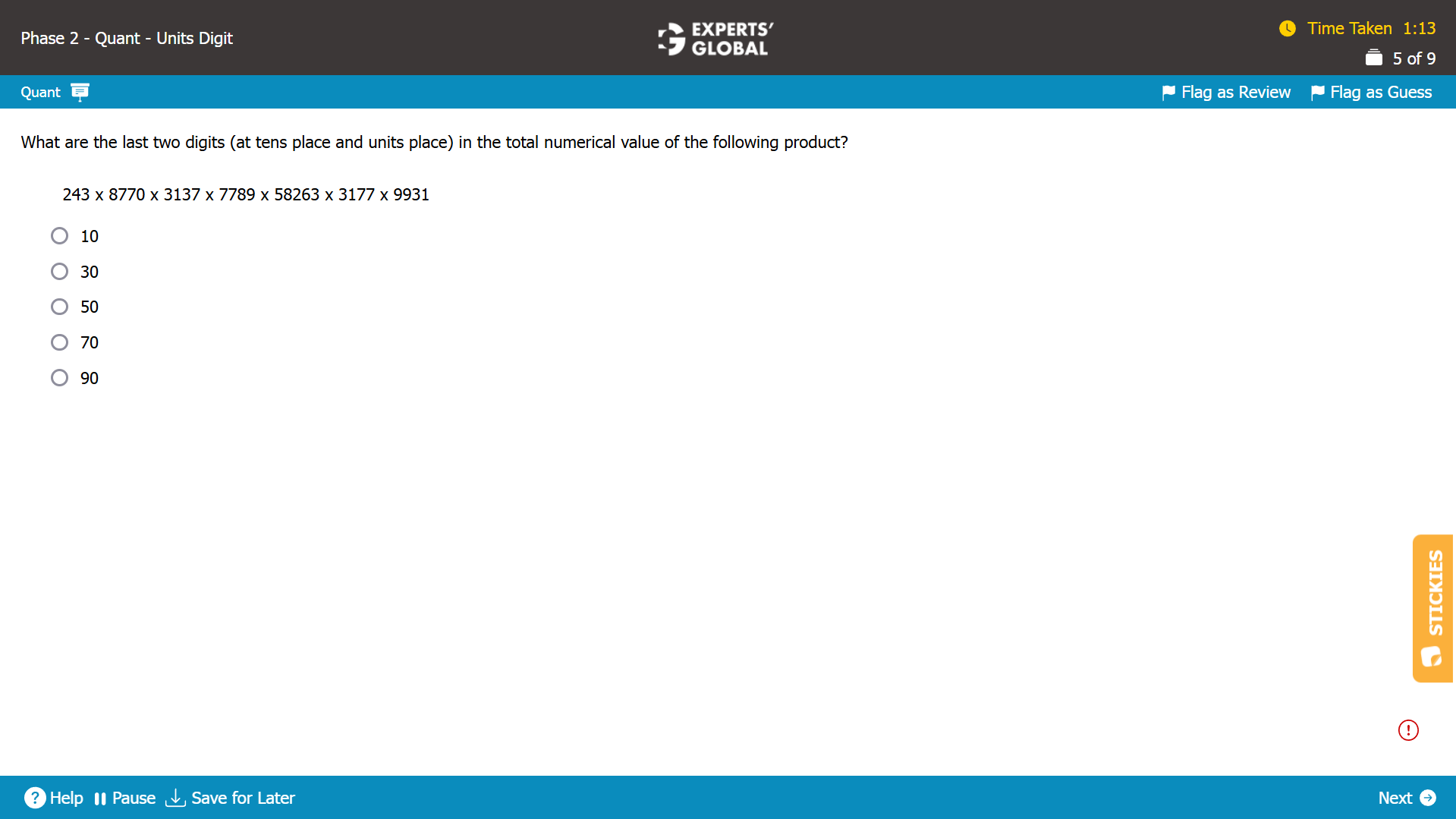

The product (243 x 8770 x 3137 x 7789 x 58263 x 3177 x 9931) is a multiple of 8770. So, the units digit of the product will be 0.

The tens digit of the product will be the units digit of (243 x 877 x 3137 x 7789 x 58263 x 3177 x 9931)

Units digit of (243 x 877 x 3137 x 7789 x 58263 x 3177 x 9931)

= Units digit of the product of the units digits of individual terms

= units digit of (3 X 7 X 7 X 9 X 3 X 7 X 1)

= units digit of (21 X 7 X 9 X 3 X 7 X 1) = units digit of (1 X 7 X 9 X 3 X 7 X 1)

= units digit of (7 X 9 X 3 X 7 X 1)

= units digit of (63 X 3 X 7 X 1) = units digit of (3 X 3 X 7 X 1)

= units digit of (9 X 7 X 1)

= units digit of (63 X 7 X 1) = units digit of (3 X 1)

= 3

So, the last two digits of the product will be 30.

B is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

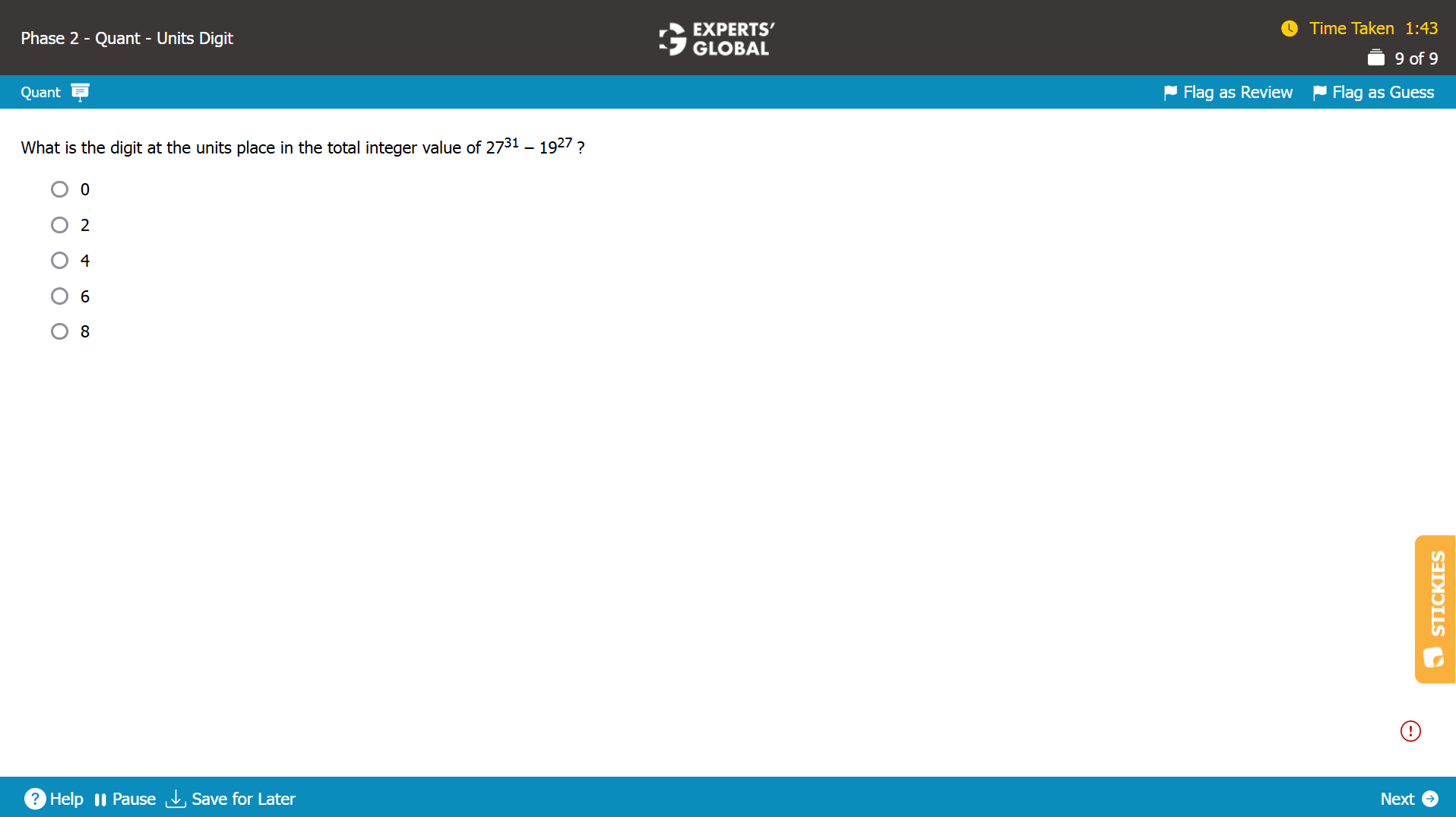

2731 has a greater base and a greater power than 1927.

So, 2731 > 1927.

Hence, units digit in the total integer value of 2731 – 1927 = units digit in 2731 – units digit in 1927.

Units digit in 2731 = units digit in 731.

71 = 7 has last digit 7.

72 will have last digit of 7 X 7 = last digit of 49 = 9.

73 will have last digit of 9 X 7 = last digit of 63 = 3.

74 will have last digit of 3 X 7 = last digit of 21 = 1.

75 will have last digit of 1 X 7 = last digit of 7 = 7.

From the 5th power onwards, the last digits will repeat in the {7, 9, 3, 1} cycle with 4 terms.

31 = 4 X 7 + 3; so, 31 leaves the remainder of 3 in the cycle of 4.

So, the 31 – 3 = 28th power will complete 7 cycles of {7, 9, 3, 1}, and the 31st power will have the units digit of 3, the third term in the cycle.

So, units digit in 2731 = 3.

Units digit in 1927 = units digit in 927.

91 = 9 has last digit 9.

92 will have last digit of 9 X 9 = last digit of 81 = 1.

93 will have last digit of 1 X 9 = last digit of 9 = 9.

From the 3rd power onwards, the last digits will repeat in the {9, 1} cycle with 2 terms.

27 = 2 X 13 + 1; so, 27 leaves the remainder of 1 in the cycle of 2.

So, the 27 – 1 = 26th power will complete 13 cycles of {9, 1}, and the 27th power will have the units digit of 9, the first term in the cycle.

So, units digit in 1927 = 9.

Overall.

Units digit in the total integer value of 2731 – 1927 = units digit in 2931 – units digit in 1927 = 3 – 9

Please note that because 9 is greater than 3 and because the last digit cannot be negative, there will be a carry that needs to be borrowed in this subtraction. In other words, the units digit will be the units digit of (13 – 9), rather than (3 – 9).

So, units digit in the total integer value of 2731 – 1927 = 13 – 9 = 4.

Units digit in the total integer value of 2731 – 1927 will be 4.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

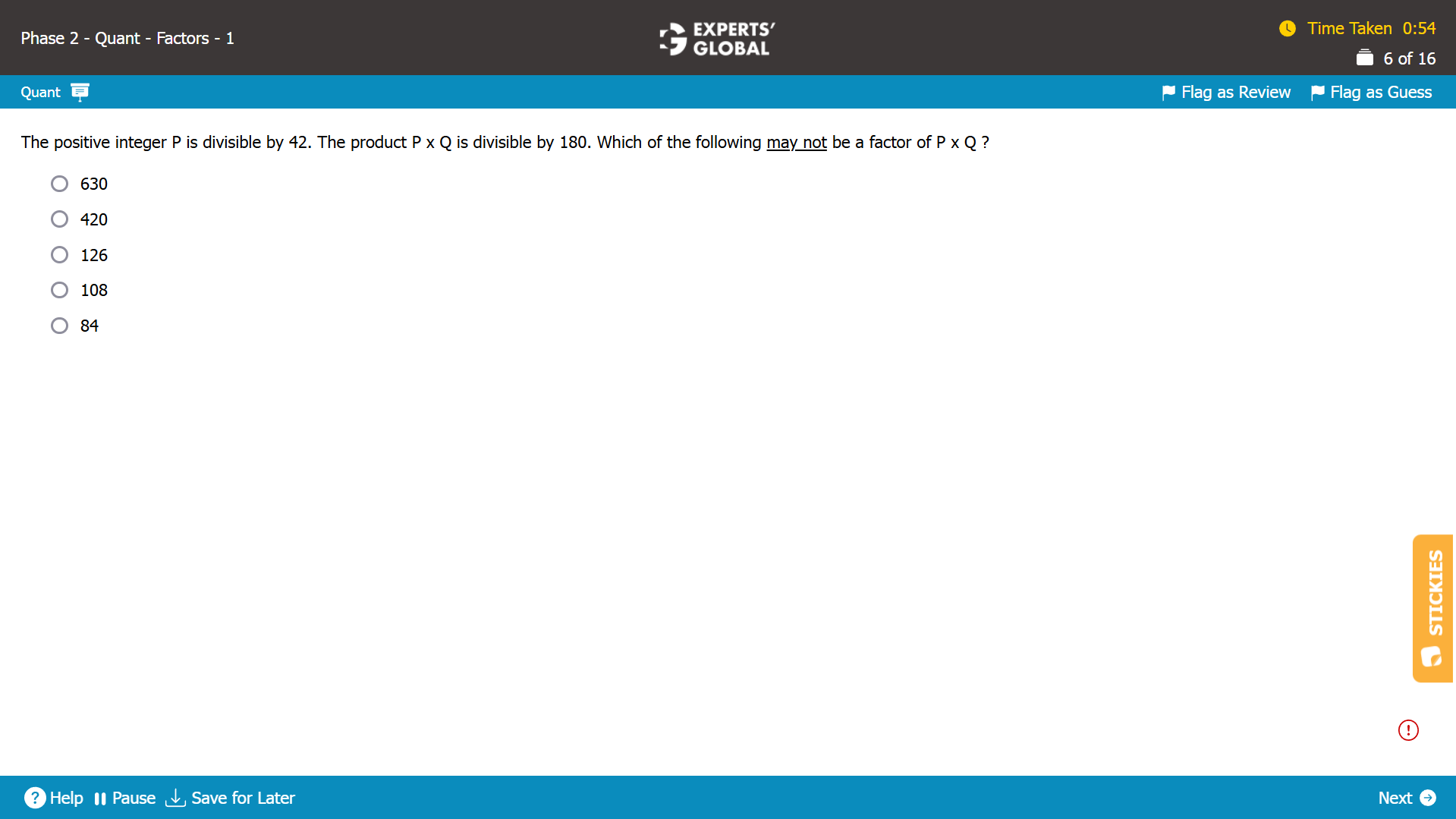

Written Explanation

42 = 2 X 3 X 7

P is divisible by 42.

So, P is divisible by 2, 3, and 7 … (Statement I)

180 = 2 X 2 X 3 X 3 X 5

For (P X Q) to be divisible by 180, (P X Q) needs to have 2 2s, 2 3s, and one 5.

One 2 and one 3 can be provided by P.

One 5 cannot be provided by P.

So, Q must have the other 2, the other 3, and one 5.

So, Q must be divisible by 2, 3, and 5 … (Statement II)

630 = 2 X 3 X 3 X 5 X 7

630 needs one 2, 2 3s, one 5, and one 7.

From Statement I and Statement II, it can be inferred that…

(P X Q) will have at least 2 2s, at least 2 3s, at least one 5, and at least one 7. So, one 2, 2 3s, one 5, and one 7 required for 630 exist in (P X Q).

So, 630 must be a factor of (P X Q).

420 = 2 X 2 X 3 X 5 X 7

420 needs 2 2s, one 3, one 5, and one 7.

From Statement I and Statement II, it can be inferred that…

(P X Q) will have at least 2 2s, at least 2 3s, at least one 5, and at least one 7. So, 2 2s, one 3, one 5, and one 7 required for 420 exist in (P X Q).

So, 420 must be a factor of (P X Q).

126 = 2 X 3 X 3 X 7

128 needs one 2, 2 3s, and one 7.

From Statement I and Statement II, it can be inferred that…

(P X Q) will have at least 2 2s, at least 2 3s, at least one 5, and at least one 7. So, one 2, 2 3s, and one 7 required for 126 exist in (P X Q).

So, 126 must be a factor of (P X Q).

108 = 2 X 2 X 3 X 3 X 3

108 needs 2 2s and 3 3s.

From Statement I and Statement II, it can be inferred that…

(P X Q) will have at least 2 2s and at least 2 3s.

Whether (P X Q) will have 3 3s cannot be determined.

So, 108 may not be a factor of (P X Q).

84 = 2 X 2 X 3 X 7

84 needs 2 2s, one 3, and one 7.

From Statement I and Statement II, it can be inferred that…

(P X Q) will have at least 2 2s, at least 2 3s, at least one 5, and at least one 7. So, 2 2s, one 3, and one 7 required for 84 exist in (P X Q).

So, 84 must be a factor of (P X Q).

D is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

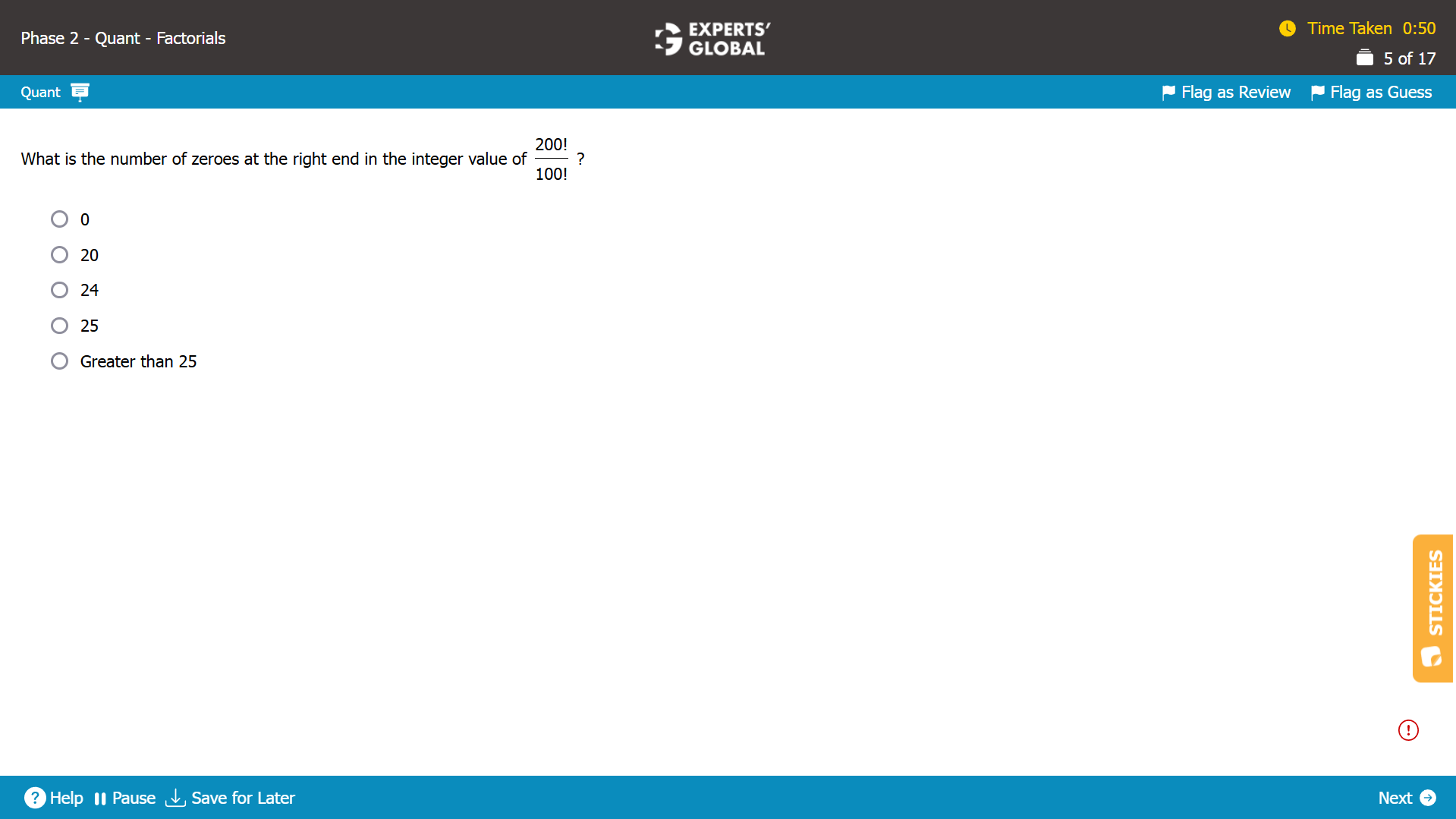

200! = 100! X (101 X 102 X 103 ..199 X 200)

So, (200! / 100!) = (101 X 102 X 103 ..199 X 200) = X, say.

The number of zeroes at the right end of X = number of 10s in X = number of (2 X 5) products in X.

Because 2s occur more frequently than 5s, there will be more 2s than 5s in X!.

So, the number of zeroes at the right end of X will be determined by the number of 5s in X.

Multiples of 5 between 101 and 200 = multiples of 5 in a range of 100 = 100 / 5 = 20.

Each of these multiples will have a 5 as a factor.

So far, number of 5s in X = 20.

Multiples of 52 = 25 between 101 and 200 = multiples of 25 in a range of 100 = 100 / 25 = 4.

Each of these multiples will have a 5 as a factor.

The first of the 5s is already counted because a multiple of 52 is also a multiple of 5.

There are 4 new 5s to be counted.

So far, number of 5s in X = 20 + 4 = 24.

Multiples of 53 = 125 between 101 and 200 = 1.

Each of these multiples will have a 5 as a factor.

The first of the 5s is already counted because a multiple of 52 is also a multiple of 5.

The second of the 5s is already counted because a multiple of 53 is also a multiple of 52.

There is 1 new 5 to be counted.

So far, number of 5s in X = 25 + 1 = 25.

There are no multiples of 54 between 101 and 200.

Overall, total number of 5s in between 101 and 200 = 25.

There will be 25 zeroes at the right end of (200! / 100!).

D is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

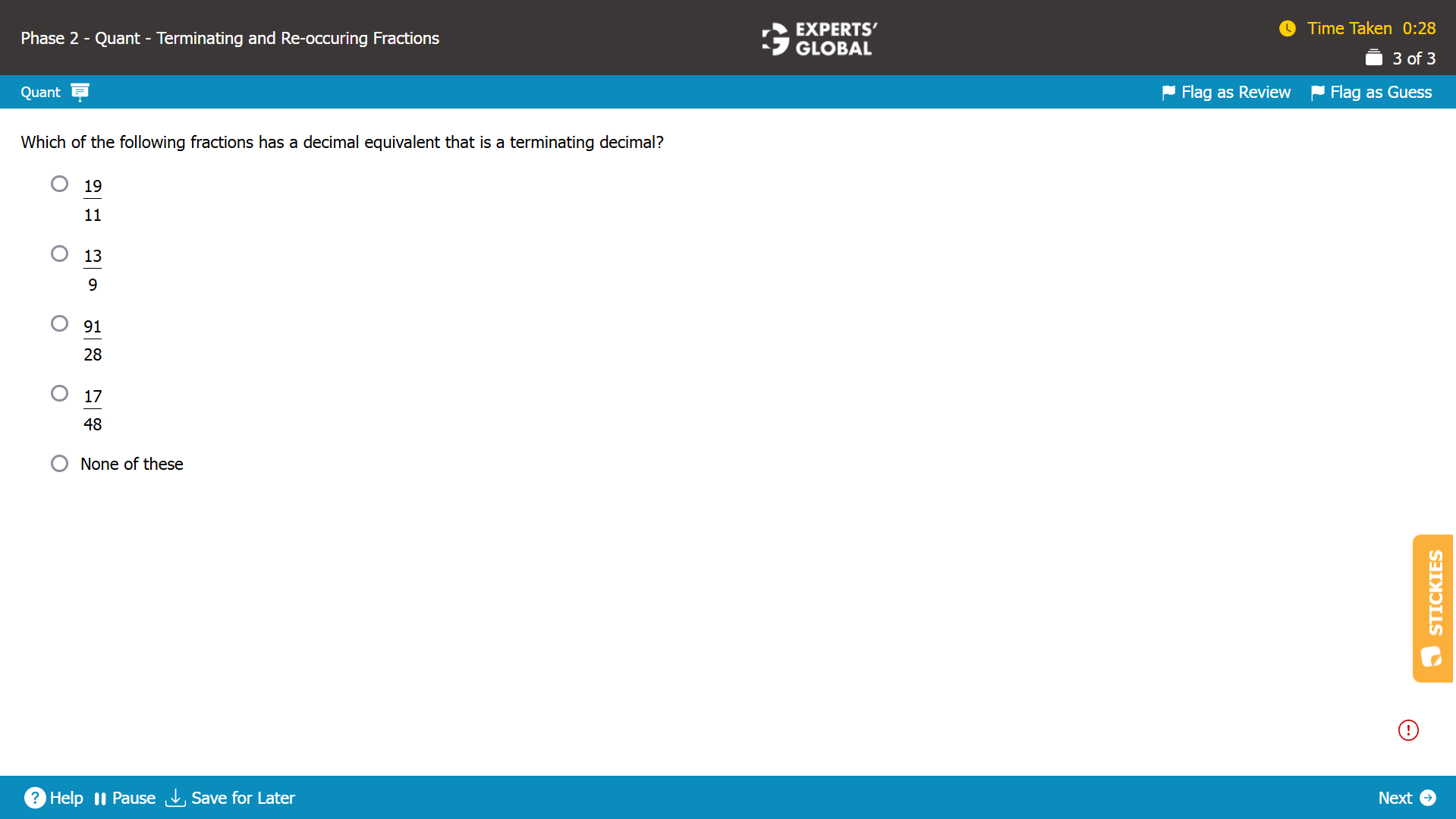

A fraction would be a terminating decimal if its denominator has 2 and 5 as the only prime factors.

A. The denominator = 11, a prime number.

There is no 11 in the factors of numerator = 19. So, the 11 in the denominator will remain.

Overall, 19 / 11 has a denominator that does not have 2 and 5 as the only prime factors. So, the fraction will not terminate.

B. The denominator = 9 = 3 X 3 = {3}

There is no 3 in the factors of numerator = 13. So, the 3 in the denominator will remain.

Overall, 13 / 9 has a denominator that does not have 2 and 5 as the only prime factors. So, the fraction will not terminate.

C. The denominator = 28 = 2 X 2 X 7 = {2,7}

There is a 7 in the factors of the numerator = 91 = 7 X 13. So, the 7 in the denominator will not remain.

Overall, 91 / 28 has a denominator that has 2 as the only prime factor. The fraction will terminate.

D. The denominator = 48 = 2 X 2 X 2 X 2 X 3 = {2, 3}

There is no 3 in the factors of numerator = 17. So, the 3 in the denominator will remain.

Overall, 17/ 48 has a denominator that does not have 2 and 5 as the only prime factors. So, the fraction will not terminate.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

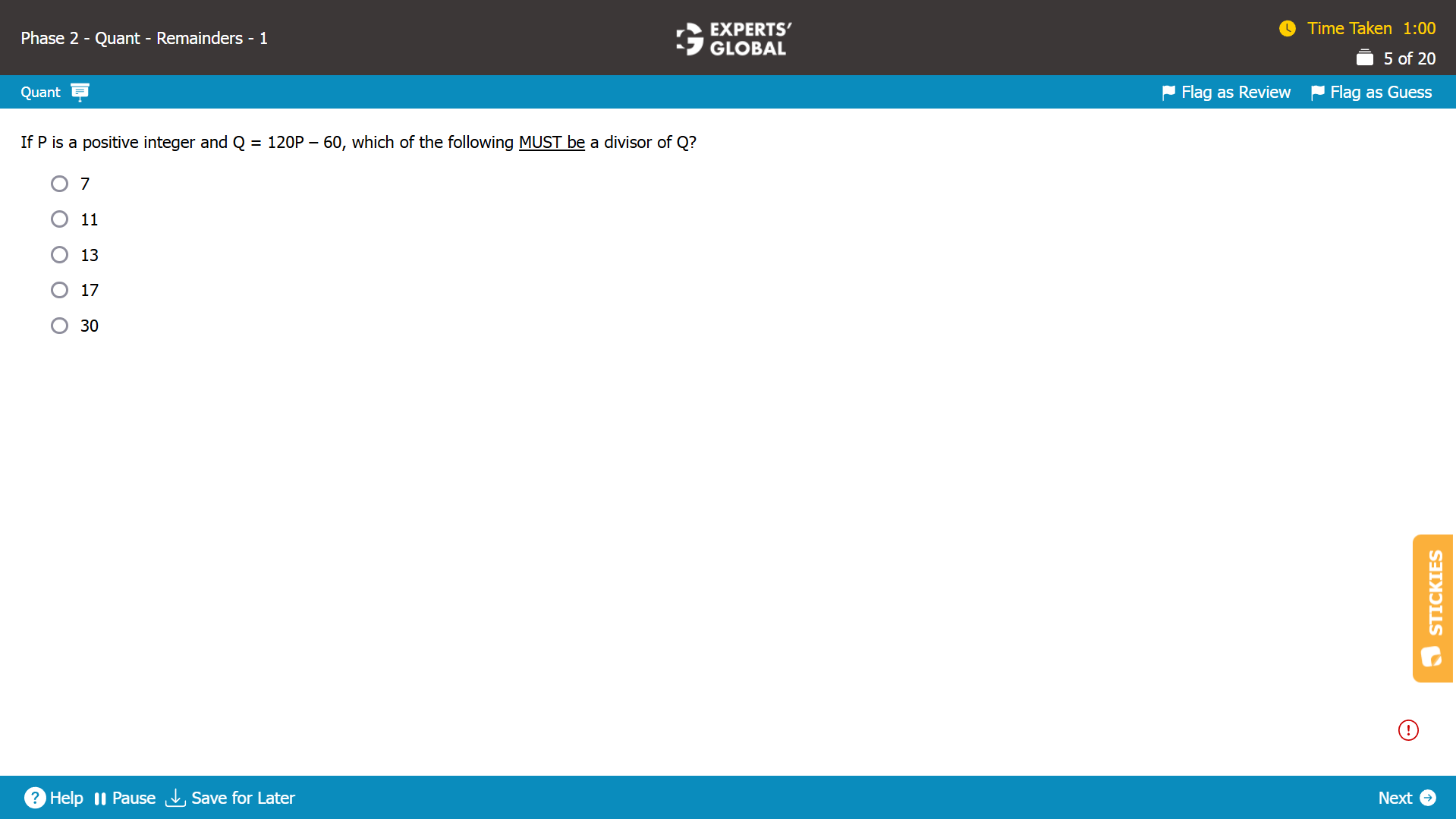

P is a positive integer.

So, 120P is a multiple of 120, 60, 30, 15, 5, 3, and 2.

60 is a multiple of 30, 15, 5, 3, and 2.

The common set of divisors is {30, 15, 5, 3, 2}.

So, Q = (120P – 60) will be a multiple of 30, 15, 5, 3, and 2.

From the given answer choice, 30 is the only number that must divide Q.

E is the correct answer choice.

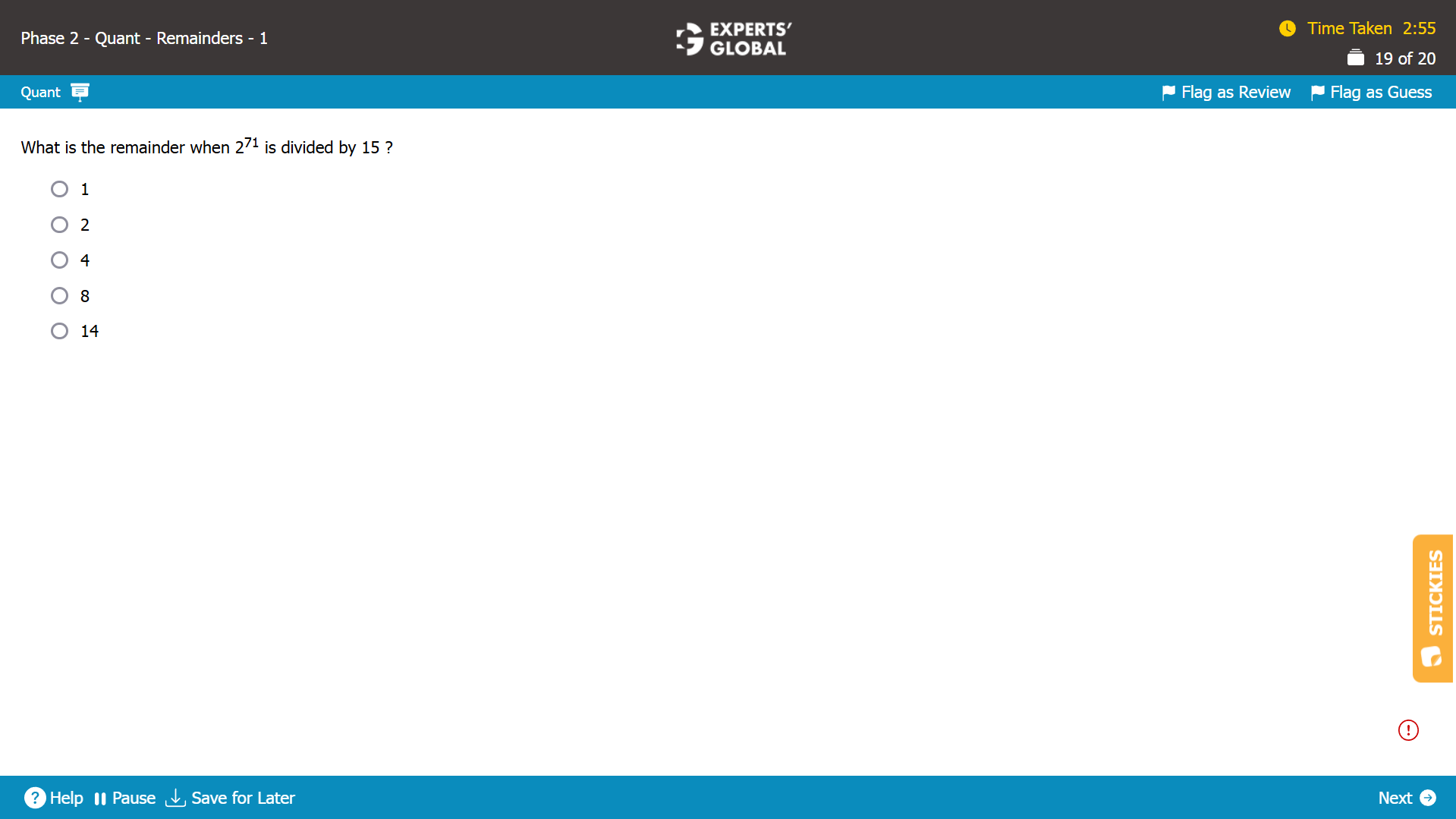

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

271 = (24)17 X 23 = 1617 X 8.

Remainder when 271 is divided by 15 = remainder when (1617 X 8) is divided by 15

= (remainder when 16 is divided by 15)17 X (remainder when 8 is divided by 15)

= 117 X 8

= 8

So, the remainder when 271 is divided by 15 is 8.

D is the correct answer choice.

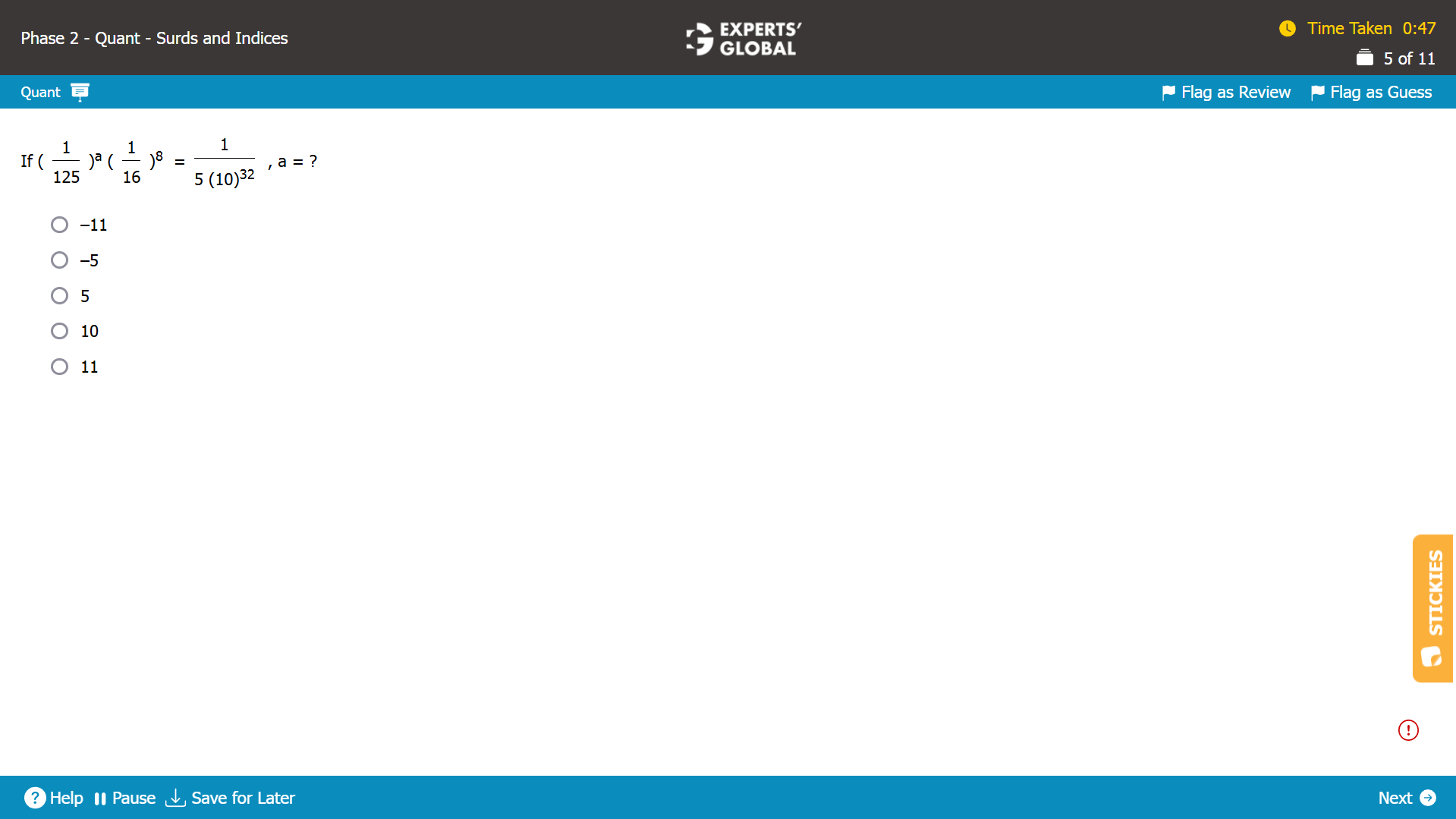

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

( 1 / 125 )a ( 1 / 16 )8 = 1 / 5 (10)32 … (Equation I)

Let’s get all the terms in prime numbers.

(1 / 125 )a = (1 / (53))a = 1 / 53a

(1 / 16 )8 = (1 / 24 )8 = 1 / 232

1 / 5 (10)32 = 1 / (5 X 232 X 532) = 1 / (232 X 533)

Substituting these terms in Equation I…

(1 / 53a) X (1 / 232) = 1 / (232 X 533)

53a = 533

3a = 33

a = 11

E is the correct answer choice.

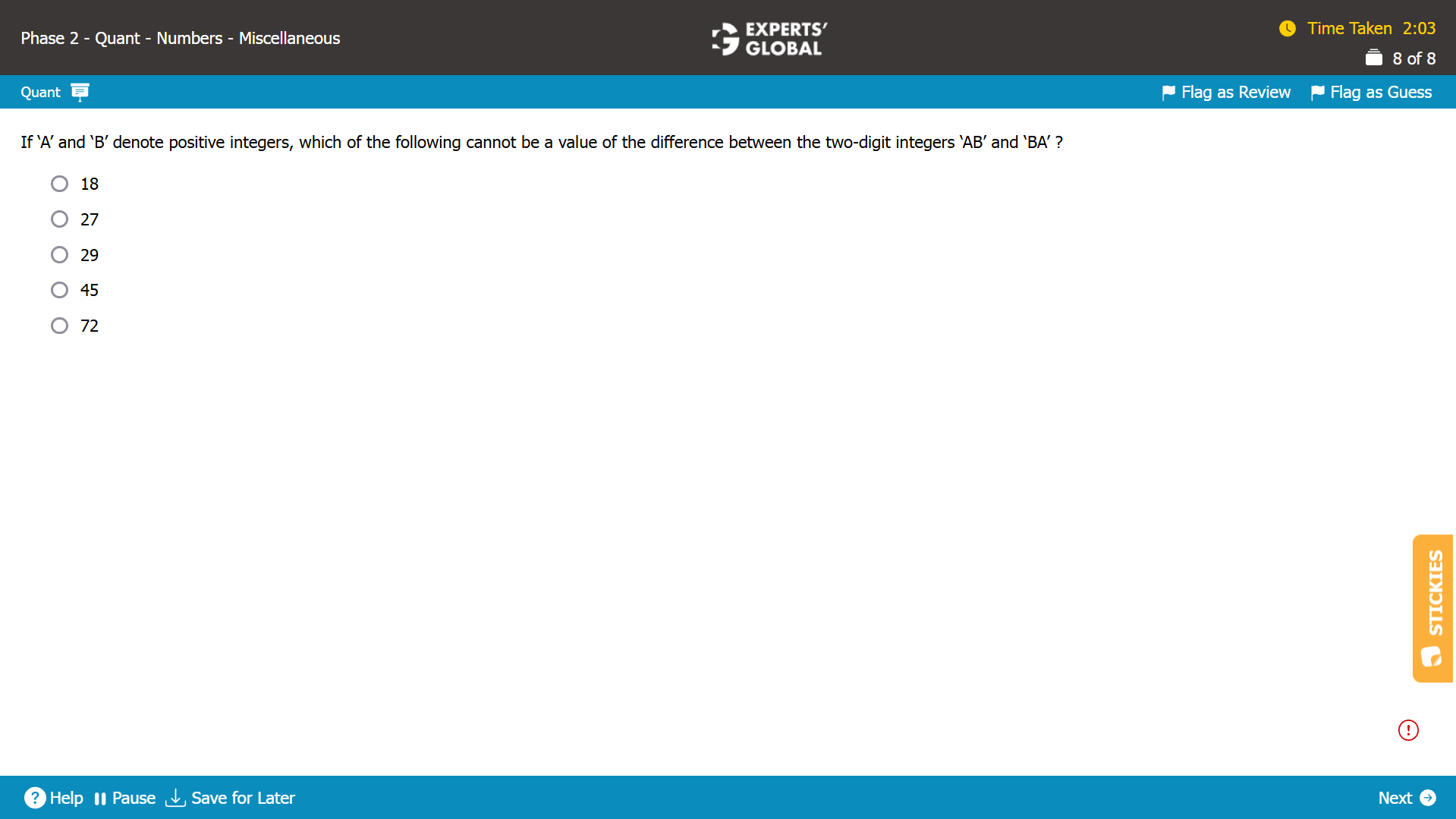

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

“AB” = 10A + B

“BA” = 10B + A

“AB” – “BA” = (10A + B) – (10B + A) = 9A – 9B = 9 (A – B).

So, the difference between “AB” and “BA” will be a multiple of 9.

From the given answer choices, 29 is the only answer choice that is NOT a multiple of 9.

29 cannot be a value of the difference between the two-digit integers “AB” and “BA”.

C is the correct answer choice.

Real practice for Number Systems problems begins when you solve them on a software platform that closely mirrors the official GMAT interface. You need a setup that presents the question stem and answer choices in a GMAT like layout, lets you work smoothly with the given information, and offers all the on screen tools and functions that appear on the actual test. Without this kind of environment, it is difficult to feel completely ready for exam day. High quality Number Systems questions are also not available in great volume. Among the limited, truly reliable sources are the official practice materials released by GMAC and the Experts’ Global GMAT course.

Within the Experts’ Global GMAT online preparation course, every Number Systems problem appears on an exact GMAT like interface that includes all the real exam tools and features. You solve more than 250 Number Systems questions through quizzes and also take 15 full-length GMAT mock tests that include several Number Systems questions in roughly the same distribution and proportion in which they appear on the actual GMAT.

All the best!