Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Logical fallacy Critical Reasoning questions on the GMAT appear in standard formats such as resolve the paradox, strengthen, weaken, and assumption questions. However, beneath these familiar labels lies a single core skill: recognizing the logical fallacy in the argument, a skill that lies at the heart of solving these questions successfully. Such questions help you understand why an argument breaks down and how weak logic can lead to an unreliable conclusion. Careful practice with this question type is an essential part of any trusted GMAT preparation course. This page offers you an organized subtopic wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

This overview presents an important logic theme in GMAT Critical Reasoning: separating cause from effect. You will learn to test the direction of influence, watch for hidden third factors, and apply fast checks such as timelines, controlled comparisons, and counterexamples to judge causal claims across multiple CR question types. The video establishes the overall framework, while the article offers a concise checklist to support disciplined, sharp analysis. The video below walks through this approach, illustrates it clearly, and helps you put it to work in GMAT drills, sectional tests, and full-length GMAT simulations.

A correlation between two events does not automatically establish that one causes the other. In GMAT Critical Reasoning, every proposed causal link should be tested by reviewing the sequence of events, searching for alternative explanations, and asking whether the supposed effect could in fact be the cause. These checks help you decide whether to strengthen, weaken, or evaluate a causal claim. The video demonstrates this process in action, while the article provides a brief checklist and compact examples for targeted practice. The short video below gives a grounded view of this concept and illustrates how the GMAT can test it.

Comparative arguments frequently rest on unspoken assumptions about how groups started out. This overview presents the idea of a baseline equivalence check: before crediting a program or event for any change in outcomes, first verify that the groups were similar on the key initial conditions. Look carefully for prior patterns, selection effects, pre-test measures, and other confounding factors, and then assess the claim. The video introduces the central diagnostic tools, while the article provides practical examples and prompts for practice. The following short video supports a clear understanding of this idea and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

Analogies clarify arguments when the likenesses genuinely matter and stay proportional. This overview explains how GMAT Critical Reasoning judges analogical claims: pinpoint what is being compared, state which feature is carried across, and check whether the situations, mechanisms, and limits correspond. You will learn to tell strong parallels from shallow ones, preparing you for the video and the stepwise article that follow. This short video clearly explains this concept and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

GMAT Critical Reasoning questions built around faulty generalizations test whether a conclusion’s reach truly fits the support behind it. This overview shows how sweeping claims based on small, biased, or uncontrolled samples are spotted and refined by examining coverage, representativeness, and alternative explanations. You will learn to notice when a claim goes too far and to favor conclusions that match the data before you engage with the options. The brief video below walks you through this concept and demonstrates how it appears on the GMAT. In this concise video, the concept is explained and its typical GMAT testing pattern is illustrated.

This overview explains circular reasoning: arguments that quietly assume the very point they claim to prove, using the conclusion itself as support. On GMAT Critical Reasoning, you learn to map the premises, check whether any real independent evidence exists, and notice disguised restatements or self-referencing loops. The video walks you through quick checks, while the article offers crisp tests and examples you can rely on under time pressure. This quick video lesson clarifies the concept and highlights how it is tested on the GMAT.

On GMAT Critical Reasoning, the impressed by numbers fallacy leans on striking statistics to persuade without showing why they matter or offering firm support. This overview presents a careful way to read numerical information in Critical Reasoning. You will see how to interpret percentages, ratios, and comparative claims by checking context, scale, and relevance before tying any figure to a conclusion. We also preview quick protective questions that guard against unexamined numbers and help you evaluate arguments in strengthen, weaken, explanation, and evaluation tasks. The following video offers a short explanation of this concept and shows how it can feature on the GMAT.

Critical Reasoning often rewards steady attention to an argument’s central claim. This lesson shows you how to locate the main point, chart the supporting premises, and check whether answer choices truly address that claim instead of wandering toward side benefits or loose facts. You will practice sensing relevance in dialogues and ruling out options that sound sensible yet quietly avoid the core issue. This compact video breaks down the concept and illustrates how it is examined on the GMAT.

On GMAT Critical Reasoning, never assess numbers in isolation. Numerical statements need context: percentages require their reference bases, and absolute figures need a clear sense of scale. A striking percentage on a very small base may still be weak, while modest growth can win in overall totals. Always match like with like, watch for missing baselines or populations, and stay alert to unsupported jumps between different kinds of claims. This overview presents a steady lens for judging such statements, showing you how to align measures, confirm baselines and populations, and avoid turning rates into totals (or totals into rates) without support. The video introduces a checklist you can use across strengthen, weaken, evaluate, and explanation questions, reinforcing evidence-oriented habits developed in GMAT preparation and the quantitative reasoning valued in MBA admissions. In the short video here, you will see the concept explained and applied to GMAT style questions.

Self comparison in GMAT Critical Reasoning arises when an argument measures performance only against its own past or internal standards, and then draws conclusions without any outside benchmark. This overview explains why such claims need context in the form of bases, peer groups, and meaningful criteria. You will see how this flaw shows up in weaken, evaluate, and explanation questions, and how to test it by actively looking for comparable cases. This brief video tutorial explains the concept and demonstrates the way it can be tested on the GMAT.

Mistaking what is necessary for what is sufficient is a classic reasoning trap on GMAT Critical Reasoning. This piece explains how to separate conditions that are required from those that truly ensure a result, and how to use that clarity across common CR question types such as assumption, strengthen, weaken, and evaluation. You will preview simple diagnostic questions, symbolic hints, and short illustrative cases that the article develops in more detail later. The video below provides a quick explanation of this concept and shows how it is used in GMAT questions.

GMAT Critical Reasoning often checks whether you can tell sufficient conditions from necessary ones. This overview clarifies that distinction, shows how arguments wrongly trade one for the other, and introduces a practical test: locate the stated condition, ask whether it truly secures the outcome or only needs to be present, and then look for counterexamples. The video applies this perspective to strengthen, weaken, and evaluation questions. This short clip explains the idea in detail and illustrates how it can appear on the GMAT.

Critical Reasoning sometimes tests whether you can tell the difference between what may happen and what must happen. This overview explains the line between possibility and necessity, with a focus on subset and superset relationships, conditional patterns, and careful inference. You will see how this lens clarifies certain assumption, inference, and evaluation questions and protects you from drawing firm claims from optional conditions. After the video, you can use the article to formalize these checks and work through focused examples. In this short video explanation, the concept is unpacked and its GMAT applications are demonstrated.

Grasping subset and superset relationships is sometimes at the heart of Critical Reasoning. This overview explains how facts about a smaller group do not always carry over to the larger group, and how features of a whole do not automatically describe each individual within it. By sketching overlaps and boundaries before you judge any claim, you can avoid faulty inferences and see more clearly what must be true and what only might be true. The following brief video clarifies this concept and shows how the GMAT can test it.

In this section, you will practise a series of GMAT-style Critical Reasoning questions built around common logical fallacies, each accompanied by a careful, stepwise explanation. Take your time with every argument and consciously apply the ideas and techniques you have just studied on this page for spotting flawed reasoning on the GMAT. At this stage, give priority to using the fallacy framework accurately rather than simply arriving at the credited option. After you lock in your answer, use the explanation toggle to view the correct choice and to read the full descriptive reasoning.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

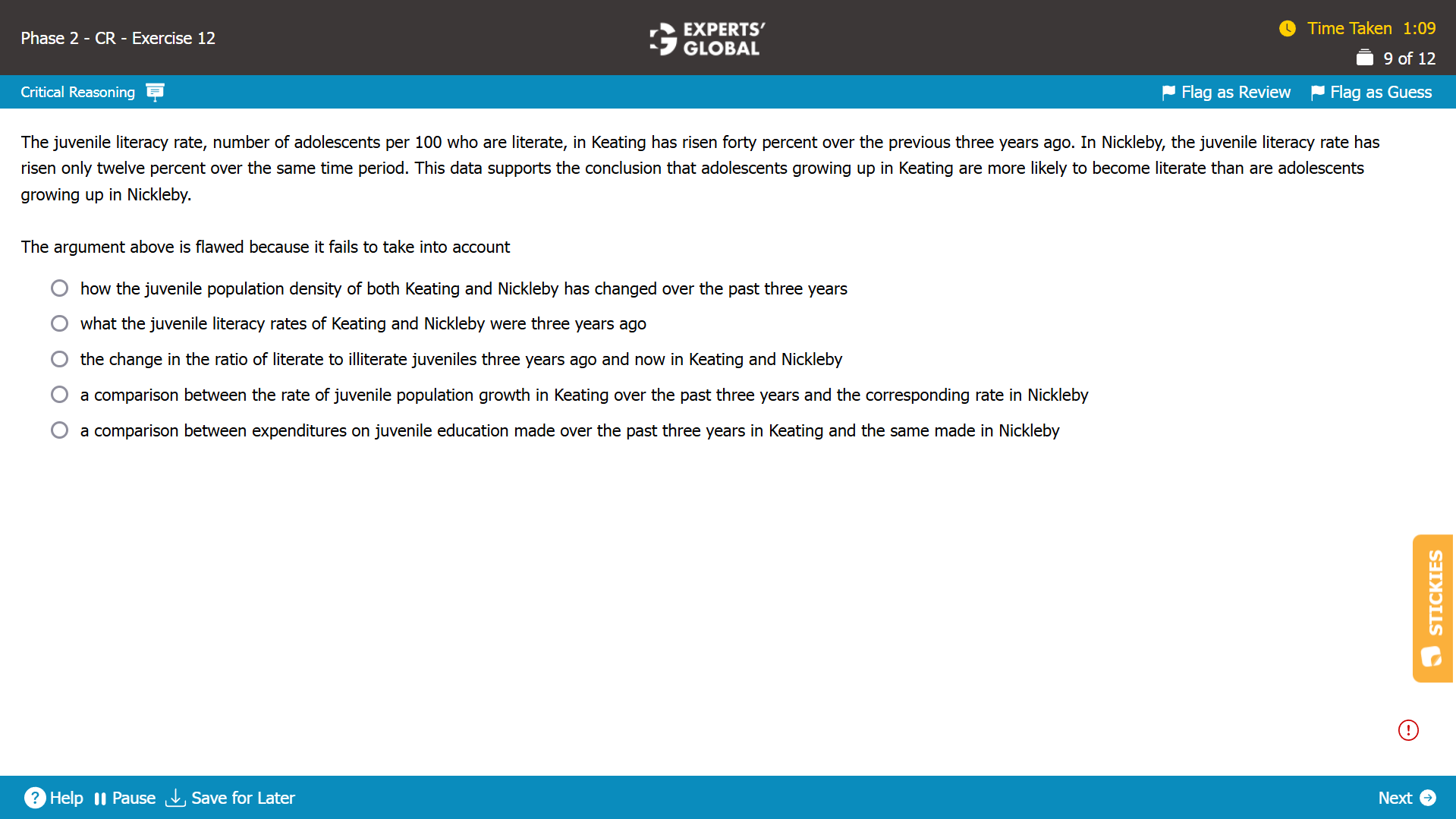

Mind-map: Juvenile literacy rate in Keating increased forty percent in three years → that in Nickleby increased twelve percent → Keating adolescents are more likely to become literate than Nickleby adolescents (conclusion)

Missing-link: Between all the information presented and the conclusion that Keating adolescents are more likely to become literate than Nickleby adolescents

Expectation from the correct answer choice: Something on the lines of assuming that literacy rates in the two cities were similar three years ago

Note: This question tests the classic GMAT error of assuming that two similar entities are comparable; in this argument, before making a conclusion about whether juvenile literacy rates between Juvenile and Nickleby today, one must evaluate whether their literacy rates were similar three years ago. Additionally, please be extra careful when you see numbers/percentages/proportions in CR questions; often, the key lies in the numbers.

A. Trap. The argument is concerned with juvenile literacy “rate” per 100 adolescents; so, the change in juvenile population density, meaning population per unit area, is just additional consideration and has no bearing on the argument. Because this answer choice does not indicate the information failing to account for which leads to a flaw in the argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

B. Correct. When the literacy rates in two cities are compared, a greater literacy rate increase in one city over a period of time leads to greater literacy in that city if the two cities had a similar literacy rate at the beginning of the period; in other words, without comparing the original juvenile literacy rates in Keating and Nickleby three years ago, no comparison between their literacy rates “now” can be obtained based on the increase in the literacy rate in the last three years; the argument fails to consider the piece of information mentioned in this answer choice and is thus flawed. Because this answer choice indicates the information failing to account for which leads to a flaw in the argument, this answer choice is correct.

C. Trap. The argument considers the increase in literacy rate per 100 adolescents in Keating and Nickleby over three years, suggesting that the change in the ratio of literate to illiterate juveniles in the two cities is considered in the argument. Because this answer choice does not indicate the information failing to account for which leads to a flaw in the argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

D. Trap. The argument is concerned with juvenile literacy rate “per 100 adolescents”; so, the change in “population” is just additional consideration and has no bearing on the argument. Because this answer choice does not indicate the information failing to account for which leads to a flaw in the argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

E. The argument is concerned with juvenile literacy “rate” in the two cities and not with any reason for the change in the rate; so, comparison between expenditures on juvenile education in the two cities is out of scope. Because this answer choice does not indicate the information failing to account for which leads to a flaw in the argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

B is the best choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

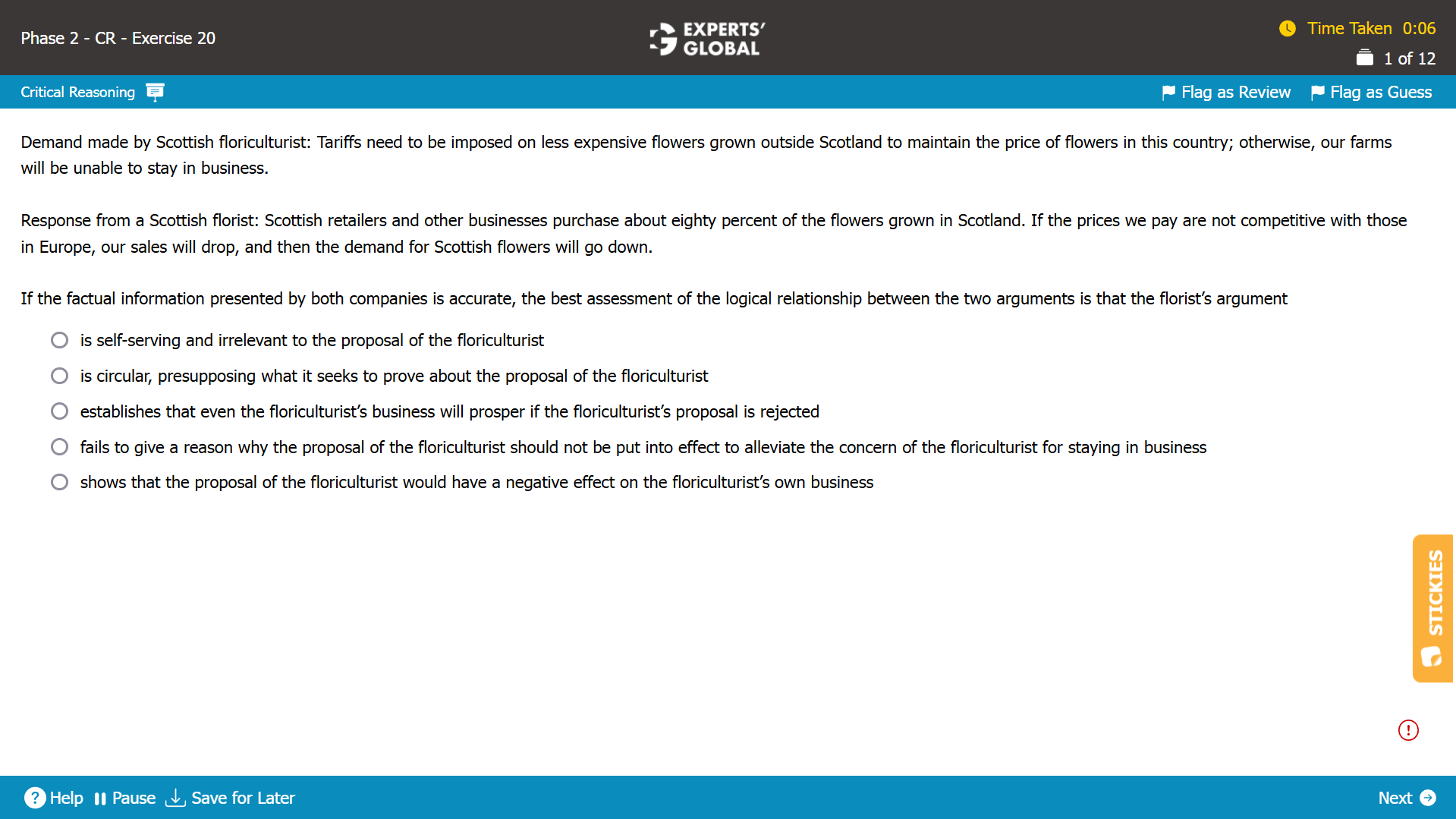

Mind-map: Floriculturist: tariffs to be implemented on inexpensive flowers from outside country → flower prices in country will be maintained → without maintaining prices, farms cannot stay in business → Florist: retailers purchase most flowers grown in country → if we don’t pay prices competitive with those elsewhere → our sales will fall → demand for flowers will go down

Missing-link: Not needed

Expectation from the correct answer choice: Something on the lines of florist arguing that if the floriculturist’s proposal to maintain flower prices is implemented, it will hurt the florist’s and the floriculturist’s businesses

A. The florist argues that if the floriculturist’s proposal to maintain flower prices is implemented, it will hurt the florist’s and the floriculturist’s businesses; so, the florist’s argument indicates a negative consequence of the floriculturist’s proposal and thus, it is incorrect to state that florist’s argument is self-serving or irrelevant to the floriculturist’s proposal. Because this answer choice does not correctly assess the logical relationship between the two arguments, this answer choice is incorrect.

B. Trap. Circular reasoning is the idea of proving a conclusion by stating/assuming that the conclusion is true; the florist argues that if the floriculturist’s proposal to maintain flower prices is implemented, it will hurt the florist’s and the floriculturist’s businesses; so, the florist’s argument indicates a negative consequence of the floriculturist’s proposal and does not involve any circular reasoning. Because this answer choice does not correctly assess the logical relationship between the two arguments, this answer choice is incorrect.

C. The florist argues that if the floriculturist’s proposal to maintain flower prices is implemented, it will hurt the florist’s and the floriculturist’s businesses; although the florist indicates the consequences of “implementing” the proposal, it makes no suggestion regarding the consequences of “rejecting” the proposal; in other words, it is incorrect to state that the florist establishes that even the floriculturist ‘s business will prosper if the floriculturist’s proposal is rejected. Because this answer choice does not correctly assess the logical relationship between the two arguments, this answer choice is incorrect.

D. Trap. The florist argues that if the floriculturist’s proposal to maintain flower prices is implemented, it will hurt the florist’s and the floriculturist’s businesses, thus indicating a negative consequence of the floriculturist’s proposal and suggesting a reason for not implementing the proposal; so, it is incorrect to state that the florist’s argument “fails” to give a reason why the proposal of the floriculturist should not be put into effect. Because this answer choice does not correctly assess the logical relationship between the two arguments, this answer choice is incorrect.

E. Correct. The florist argues that if the floriculturist’s proposal to maintain flower prices is implemented, it will hurt the florist’s and the floriculturist’s business; in other words, the florist’s argument shows that the proposal of the floriculturist would have a negative effect on the floriculturist’s own business, as the answer choice mentions. Because this answer choice correctly assesses the logical relationship between the two arguments, this answer choice is correct.

E is the best choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

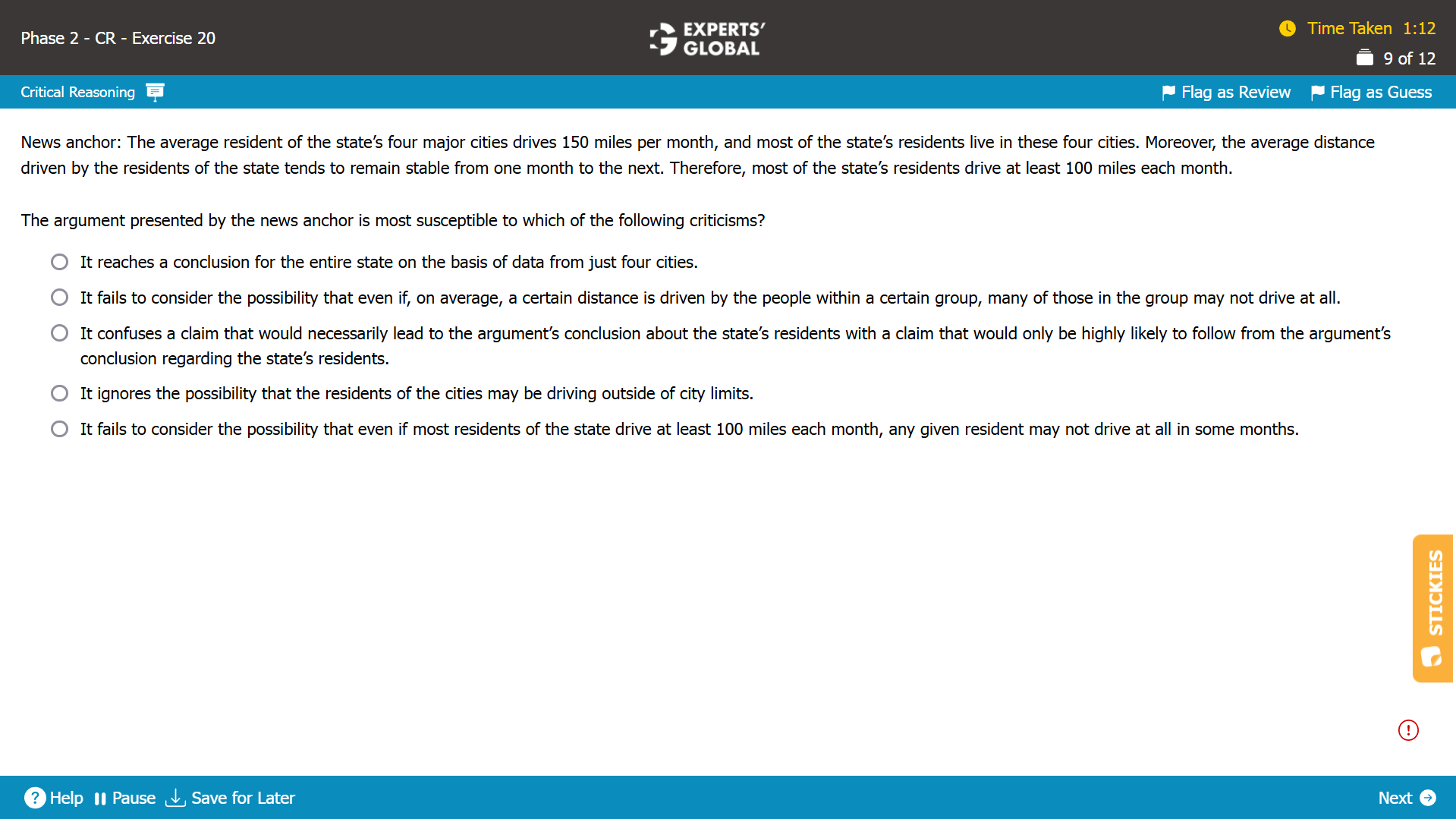

Mind-map: Average resident of four cities drives 150 miles per month → most of the state’s residents reside in these four cities → average distance driven by residents does not change → most of the state’s residents drive at least 100 miles each month (conclusion)

Missing-link: Between all the information presented and the conclusion that most of the state’s residents drive at least 100 miles each month

Expectation from the correct answer choice: Something on the lines of ignoring that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents

Note: This answer choice commits the classic GMAT error of generalization – the idea of reaching a conclusion for a superset on the basis of observations on a subset; the argument cites information about the average mileage of four major cities, a subset, and draws a conclusion about the minimum mileage contributed by most residents of the state, a superset. Besides, please be extra careful when you see numbers/percentages/proportions in CR questions; often, the key lies in the numbers.

A. Trap. The argument mentions that most of the state’s residents reside in the four major cities; so, the average distance driven by the residents of the state is likely to be close to the average distance driven by the residents of these four cities; hence, reaching a conclusion for the entire state on the basis of data from just four cities is not the flaw in the argument. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of a very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. This answer choice can stay after the first glance but shall eventually make way for a better, stronger answer choice; we have a more convincing answer choice in B.

B. Correct. The argument cites average mileage in four cities and draws a conclusion that most residents of the state are contributing by driving “at least 100 miles”; the argument ignores the possibility that the average mileage in four cities may be due to a small proportion of city residents driving a very high number of miles and other city residents driving very low number of miles or not at all; in other words, it is possible that the average resident of four cities drives 150 miles per month even if most of the state’s residents drive less than 100 miles each month; ignoring this possibility weakens the conclusion; so, the argument can be criticized on the basis of the failure to consider the possibility stated in this answer choice. Because this answer choice indicates the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is correct.

C. Trap. The argument makes neither a claim that would necessarily lead to the argument’s conclusion nor a claim that would only be highly likely to follow from the argument’s conclusion; so, it is incorrect to state that the argument confuses between these two claims, as the answer choice mentions; so, the argument cannot be criticized on the basis of the confusion stated in the answer choice. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. Because this answer choice does not indicate the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is incorrect.

D. The argument is concerned with the average distance driven by residents of the cities; where the driving takes place is just additional detail and has no bearing on the argument; so, the argument cannot be criticized on the basis of the failure to consider the possibility stated in this answer choice. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. Because this answer choice does not indicate the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is incorrect.

E. Trap. The conclusion is that most of the state’s residents drive at least 100 miles each month; it is likely that some residents drive less than 100 miles each month and that some residents do not drive at all; so, the possibility stated in this answer choice has already been accounted for in the argument; hence, the argument cannot be criticized on the basis of the failure to consider the possibility stated in the answer choice. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. Because this answer choice does not indicate the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is incorrect.

B is the best choice.

Real practice for Logical Fallacy questions begins when you solve them on a software simulation that closely matches the official GMAT interface. You need a platform that presents the flawed argument, the question stem, and the answer choices in a GMAT like layout, lets you work with the reasoning and options naturally, and provides all the on screen tools and functionalities that you will see on the actual exam. Without this kind of experience, it is difficult to feel fully prepared for test day. High quality Logical Fallacy questions are not available in large numbers. Among the limited, genuinely strong sources are the official practice materials released by GMAC and the Experts’ Global GMAT course.

Within the Experts’ Global GMAT online preparation course, every Logical Fallacy question appears on an exact GMAT like user interface that includes all the real exam tools and features. You work through more than 40 Logical Fallacy questions in quizzes and also take 15 full-length GMAT mock tests that include several Logical Fallacy questions in roughly the same spread and proportion in which they appear on the actual GMAT.

All the best!