Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

GMAT CR Method of Reasoning questions ask you to recognize the pattern of thought an argument uses, such as how it draws conclusions, uses evidence, responds to objections, or builds comparisons. These critical reasoning questions help you see not just what the argument says but how it is structured and why it works the way it does. Strong familiarity with this question type is an essential part of any comprehensive GMAT preparation course. This page offers you an organized subtopic wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient preparation of this concept.

Method-of-reasoning questions ask you to recognize how an argument is constructed. In GMAT Critical Reasoning, they form an important part of GMAT preparation because they test both your logical skills and your sensitivity to structure. Unlike strengthen, weaken, or inference questions, which focus on supporting or challenging a conclusion, method-of-reasoning questions require you to see how the author or speaker arranges the ideas and connects the steps in the argument. In the following short video, the method is laid out, shown on GMAT style questions, and readied for use in your drills, sectional tests, and full-length GMAT practice tests.

Similar Reasoning questions ask you to recognize and match the structure of an argument. Begin by reading the question stem, then break the argument into premise, assumption, and conclusion, and capture this pattern in a brief template before you look at the options. Next, compare each choice to see which one follows the same underlying skeleton while setting aside surface details. This overview presents a disciplined habit of analytical reading that supports GMAT preparation and also strengthens your ability to assess analogies in essays and interviews throughout the MBA admissions process. The short video below helps you settle this idea firmly and demonstrates how the GMAT may test it.

Flaw questions center on understanding why a conclusion fails to follow logically from its premises. This overview presents a structured way to approach them: read the question stem first, lay out the premise and conclusion, and then check for familiar error patterns such as weak analogy, false either–or choices, unsupported assumptions, treating correlation as causation, circular reasoning, and ignored alternatives. The video introduces quick diagnostic checks, while the article develops these ideas further with examples and guiding cues. The following short video presents this concept in a relaxed, clear style and shows how it can appear on the GMAT.

This section brings together a series of GMAT-style Critical Reasoning Method-of-Reasoning questions, each paired with a carefully unpacked explanation. Work through every stimulus at a steady pace and deliberately apply the analytical tools and patterns you have just studied on this page for understanding how an argument is constructed on the GMAT. At this stage, place greater weight on tracing the structure of the reasoning accurately than on simply picking an answer that appears plausible. After you select your response, use the explanation toggle to view the credited option and to review the full descriptive reasoning.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

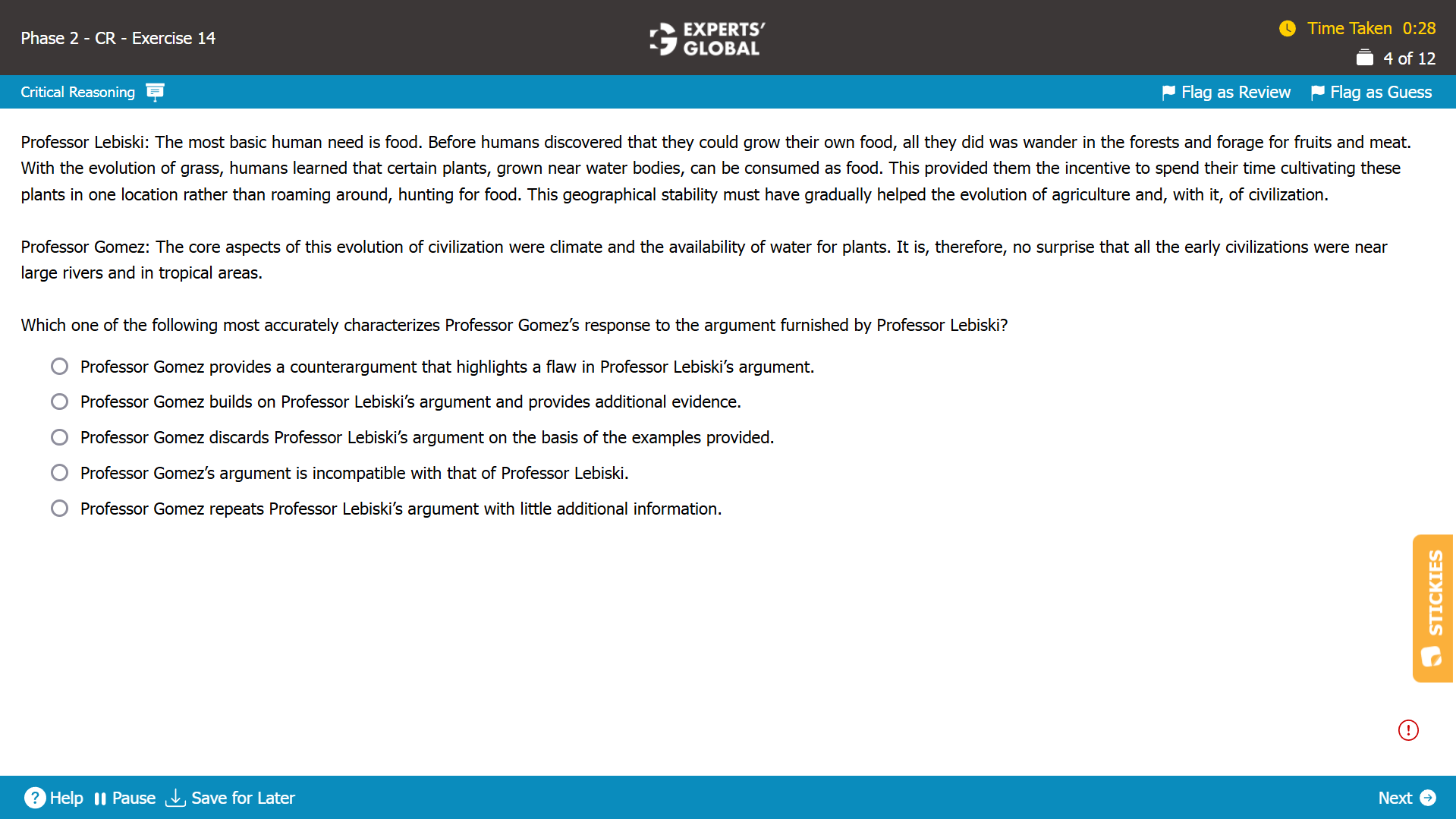

Mind-map: Professor L: food is the basic human need → after evolution of grass, humans learned to eat grass as food → humans incentivized to cultivate plants in one location → geographical stability helped evolution of agriculture and civilization→ Professor G: climate and water were important for evolution of civilization → it is not surprising that early civilizations were near tropical water bodies

Missing-link: Not needed

Expectation from the correct answer choice: Something on the lines of Professor G developing Professor L’s argument further by offering more information

A. Professor Lebiski provides information about the evolution of agriculture and civilization and Professor Gomez provides more information about the evolution of civilization; Professor Gomez builds on, rather than criticizes, Professor Lebiski’s argument; so, it is incorrect to state that Professor Gomez provides a counterargument and highlights a flaw in Professor Lebiski’s argument, as the answer choice mentions. Because this answer choice does not characterize Professor Gomez’s response to Professor Lebiski’s argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

B. Correct. Professor Lebiski provides information about the evolution of civilization, and Professor Gomez provides more information – that climate and water were important for the evolution of civilization; it can be inferred that Professor Gomez builds on Professor Lebiski’s argument and provides additional information, as the answer choice mentions. Because this answer choice characterizes Professor Gomez’s response to Professor Lebiski’s argument, this answer choice is correct.

C. Professor Lebiski provides information about the evolution of agriculture and civilization and Professor Gomez provides more information about the evolution of civilization; Professor Gomez builds on, rather than criticizes, Professor Lebiski’s argument; so, it is incorrect to state that Professor Gomez “discards” Professor Lebiski’s argument on the basis of the examples provided, as the answer choice mentions. Because this answer choice does not characterize Professor Gomez’s response to Professor Lebiski’s argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

D. Professor Lebiski provides information about the evolution of agriculture and civilization and Professor Gomez provides more information about the evolution of civilization along the lines of what Professor Lebiski provided; Professor Gomez builds on Professor Lebiski’s argument; it can be inferred that the arguments made by the two professors are compatible with each other, contrary to what the answer choice mentions. Because this answer choice does not characterize Professor Gomez’s response to Professor Lebiski’s argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

E. Professor Lebiski provides information about the evolution of civilization and Professor Gomez provides more information – that climate and water were important for the evolution of civilization; so, it is incorrect to state that Professor Gomez “simply repeats” Professor Lebiski’s argument with “little additional information”, as the answer choice mentions. Because this answer choice does not characterize Professor Gomez’s response to Professor Lebiski’s argument, this answer choice is incorrect.

B is the best choice.

Facing difficulty with such problems? Click here

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

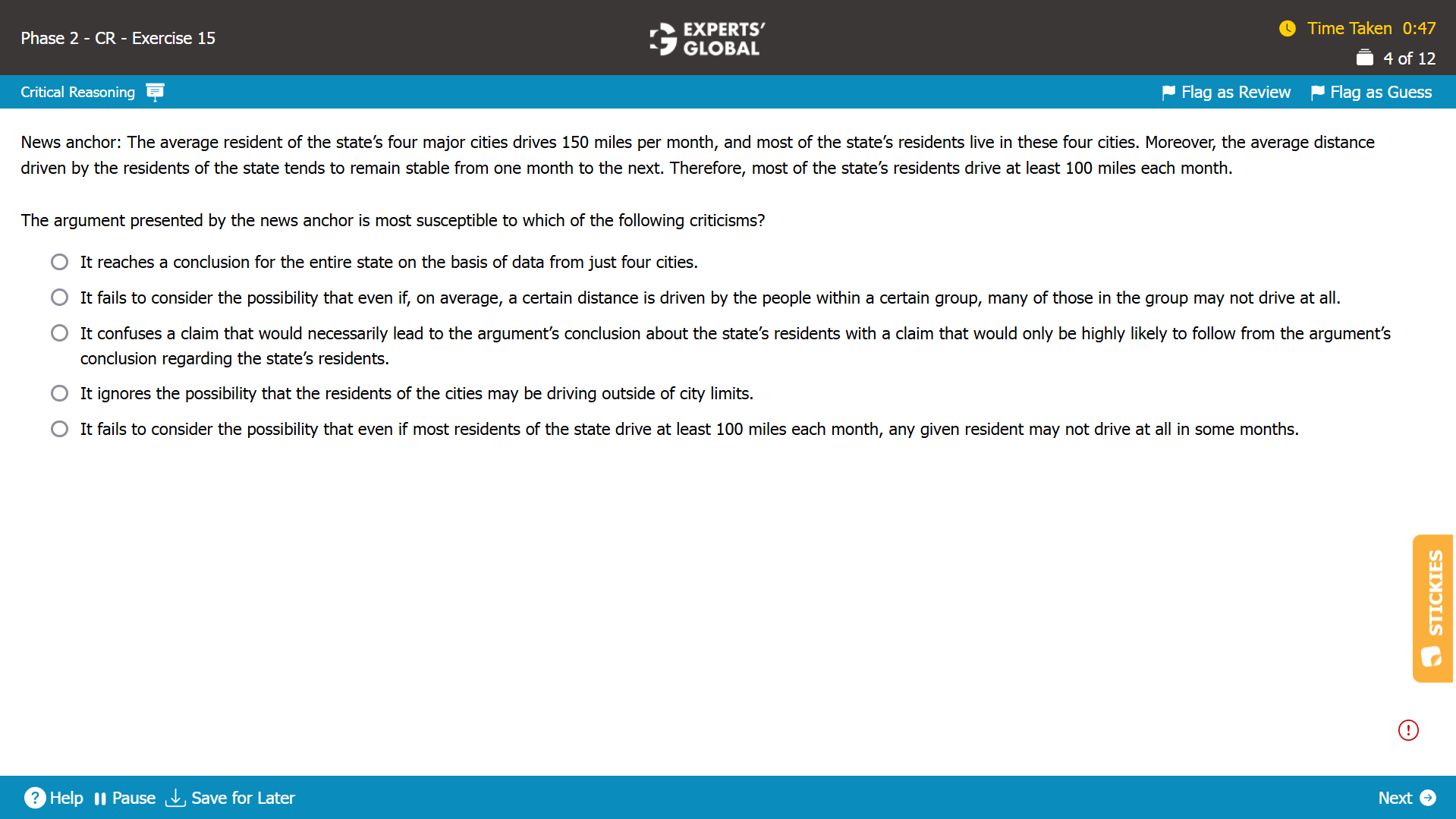

Mind-map: Average resident of four cities drives 150 miles per month → most of the state’s residents reside in these four cities → average distance driven by residents does not change → most of the state’s residents drive at least 100 miles each month (conclusion)

Missing-link: Between all the information presented and the conclusion that most of the state’s residents drive at least 100 miles each month

Expectation from the correct answer choice: Something on the lines of ignoring that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents

Note: This answer choice commits the classic GMAT error of generalization – the idea of reaching a conclusion for a superset on the basis of observations on a subset; the argument cites information about the average mileage of four major cities, a subset, and draws a conclusion about the minimum mileage contributed by most residents of the state, a superset. Besides, please be extra careful when you see numbers/percentages/proportions in CR questions; often, the key lies in the numbers.

A. Trap. The argument mentions that most of the state’s residents reside in the four major cities; so, the average distance driven by the residents of the state is likely to be close to the average distance driven by the residents of these four cities; hence, reaching a conclusion for the entire state on the basis of data from just four cities is not the flaw in the argument. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of a very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. This answer choice can stay after the first glance but shall eventually make way for a better, stronger answer choice; we have a more convincing answer choice in B.

B. Correct. The argument cites average mileage in four cities and draws a conclusion that most residents of the state are contributing by driving “at least 100 miles”; the argument ignores the possibility that the average mileage in four cities may be due to a small proportion of city residents driving a very high number of miles and other city residents driving very low number of miles or not at all; in other words, it is possible that the average resident of four cities drives 150 miles per month even if most of the state’s residents drive less than 100 miles each month; ignoring this possibility weakens the conclusion; so, the argument can be criticized on the basis of the failure to consider the possibility stated in this answer choice. Because this answer choice indicates the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is correct.

C. Trap. The argument makes neither a claim that would necessarily lead to the argument’s conclusion nor a claim that would only be highly likely to follow from the argument’s conclusion; so, it is incorrect to state that the argument confuses between these two claims, as the answer choice mentions; so, the argument cannot be criticized on the basis of the confusion stated in the answer choice. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. Because this answer choice does not indicate the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is incorrect.

D. The argument is concerned with the average distance driven by residents of the cities; where the driving takes place is just additional detail and has no bearing on the argument; so, the argument cannot be criticized on the basis of the failure to consider the possibility stated in this answer choice. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. Because this answer choice does not indicate the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is incorrect.

E. Trap. The conclusion is that most of the state’s residents drive at least 100 miles each month; it is likely that some residents drive less than 100 miles each month and that some residents do not drive at all; so, the possibility stated in this answer choice has already been accounted for in the argument; hence, the argument cannot be criticized on the basis of the failure to consider the possibility stated in the answer choice. Furthermore, the key flaw in the argument is that it ignores the possibility that the average mileage of four cities may be high because of very high mileage of only a small proportion of city residents; we need an answer choice on similar lines. Because this answer choice does not indicate the criticism that the argument is most susceptible to, this answer choice is incorrect.

B is the best choice.

Real practice for Functions problems begins when you solve them on a software simulation that closely matches the official GMAT interface. You need a platform that presents the question stem and the function definition or expression in a GMAT like layout, lets you work with the inputs, outputs, and answer choices naturally, and provides all the on screen tools and functionalities that you will see on the actual exam. Without this kind of experience, it is difficult to feel fully prepared for test day. High quality Functions questions are not available in large numbers. Among the limited, genuinely strong sources are the official practice materials released by GMAC and the Experts’ Global GMAT course.

Within the Experts’ Global GMAT online preparation course, every Functions problem appears on an exact GMAT like user interface that includes all the real exam tools and features. You work through more than 300 Functions questions in quizzes and also take 15 full length GMAT mock tests that include several Functions questions in roughly the same spread and proportion in which they appear on the actual GMAT.

All the best!