Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Percentages, mixtures, and alligation form a tightly connected idea cluster on the GMAT. Percentages express a part of a whole on a scale of 100. Mixtures describe the result of combining two or more components. Alligation offers a quick way to handle many weighted average situations within mixtures and percentages. A proper understanding of these ideas is an essential part of any comprehensive GMAT preparation course. This page provides an organized subtopic wise playlist for steady preparation of this concept along with a few worked examples.

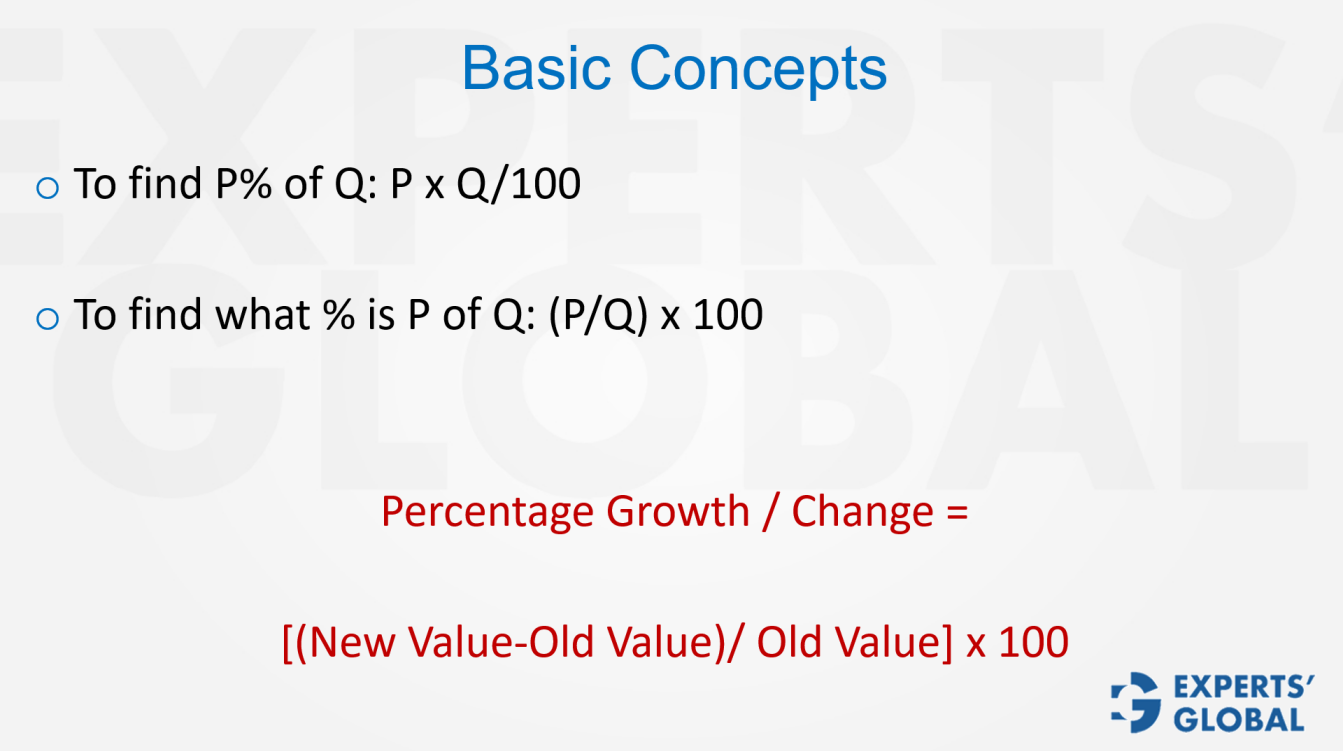

Percentage represents the “part out of 100”. To calculate percentage, divide the number (part) by the total (whole) and then multiply the result by 100. That means (part ÷ whole) * 100

Example: 30 out of 50 is (30 ÷ 50) * 100 = 60%

Percentage change shows how a value changes from its start. Use: [(new value – old value) ÷ old value] * 100.

Example: value increases from 50 to 80, change = [(80 − 50) ÷ 50] * 100 = 60% increase.

From 80 to 50, change is 37.5% decrease.

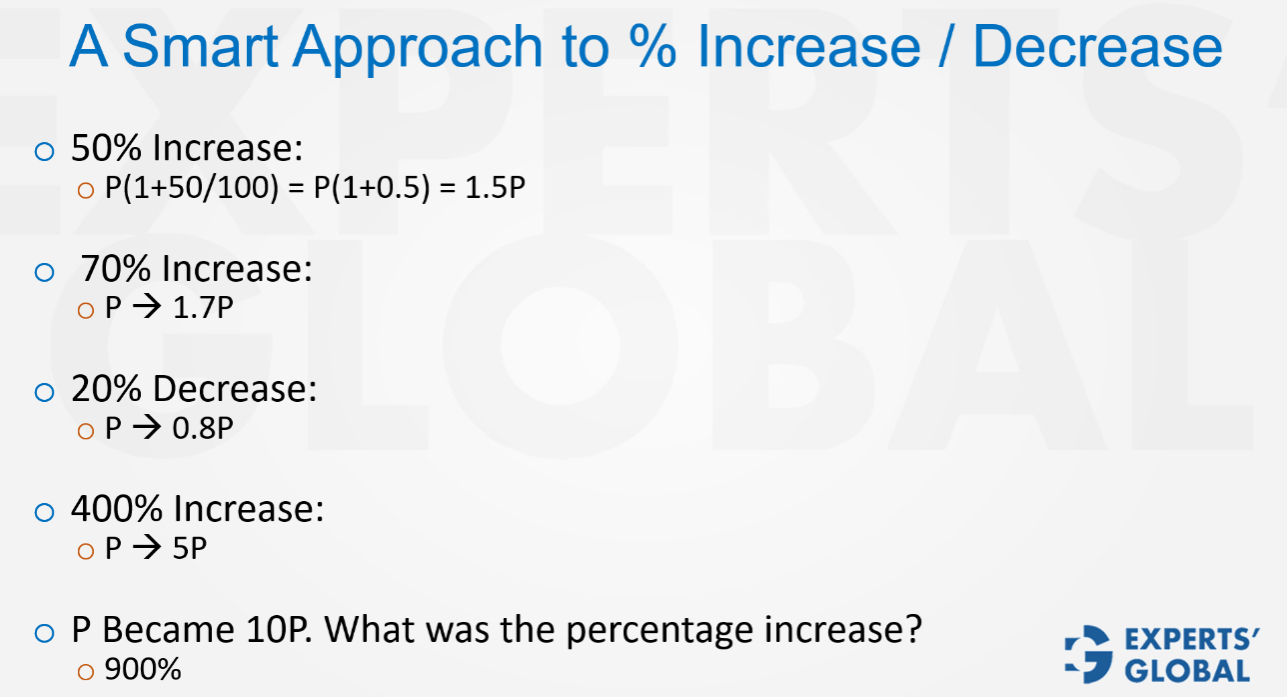

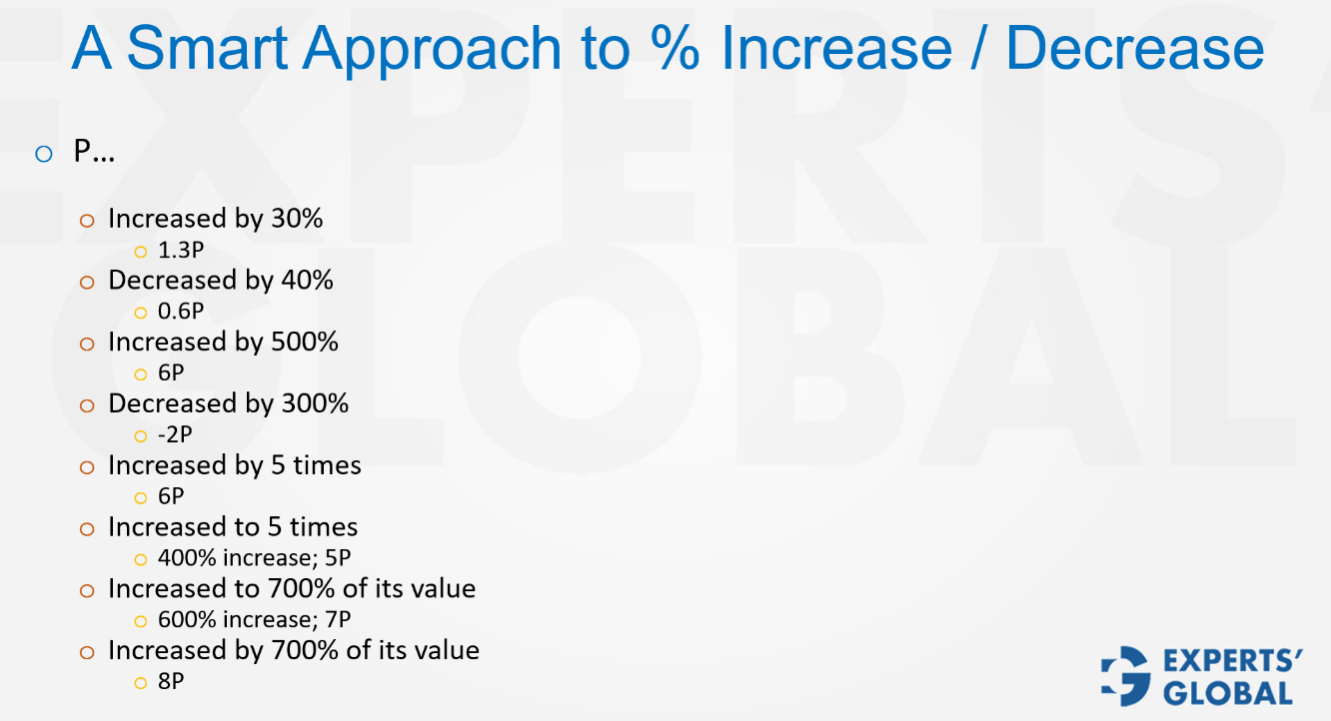

Percentage questions may appear easy at first sight, yet many test takers lose marks due to small misunderstandings in interpretation. A percentage increase or decrease can be handled in just a few seconds if you rely on a direct method instead of spreading the work into long calculations. For instance, a 50% increase does not require fractions or elaborate steps; it simply means the original quantity becomes one and a half times its value. A 20% decrease means the quantity becomes 0.8 times the starting value. Once this pattern is clear, the entire topic shifts from confusing to natural. Equally important is the difference between “increase by” and “increase to,” a distinction that many test takers blur when the pressure of the exam builds. This short video explains the method, shows it solving representative questions, and equips you to apply it in GMAT drills, sectional tests, and your full length GMAT practice tests.

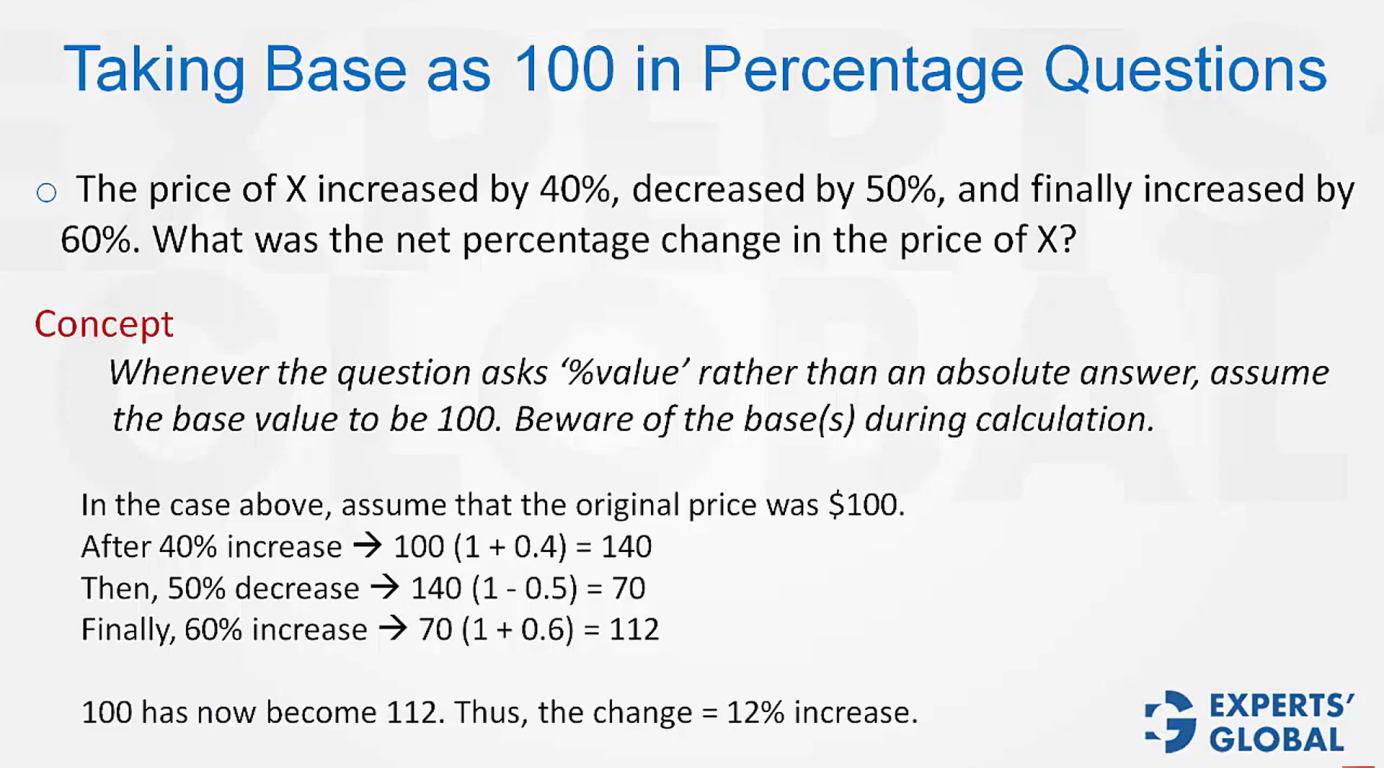

Percentage change questions often seem straightforward, yet they hide traps that can unsettle even well prepared students. The real difficulty lies not in the arithmetic but in the shifting base to which each new percentage applies. A 40% increase followed by a 50% decrease is very different from simply subtracting 10%. Each percentage works on the updated value, not on the original one. This is where many students slip, and this is exactly what the GMAT likes to test. The safest habit is to assume a base value of 100. This keeps the numbers friendly and makes it easy to see how successive percentages build on one another. A 40% decrease after a 40% rise, for example, does not take you back to your starting point but to a smaller value instead (100 → 40% increase gives 140 → 40% decrease brings it down to 84). The following brief video walks you through this idea and demonstrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

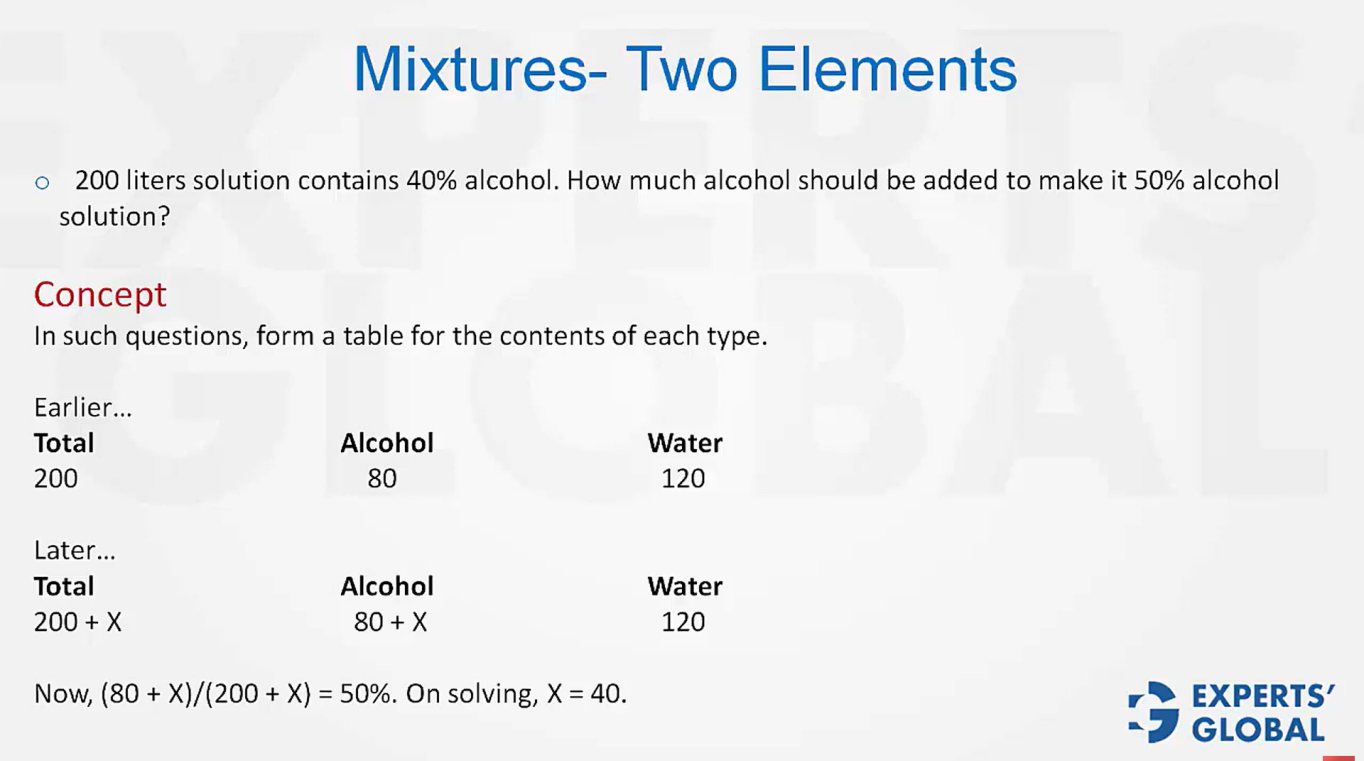

Mixture and solution questions are a staple of aptitude tests and GMAT style quantitative reasoning and deserve a firm place in your GMAT prep. They check how well you can balance percentages, proportions, and overall structure. Their main difficulty lies in the fact that whenever you add or remove one ingredient, the total quantity changes, and with it, the percentage composition shifts as well. If you overlook this, you walk straight into the trap of wrong options. A clear and dependable way to manage these problems is to set up a simple table that captures the content of each component. The short video below clarifies this idea and highlights how the GMAT can test it.

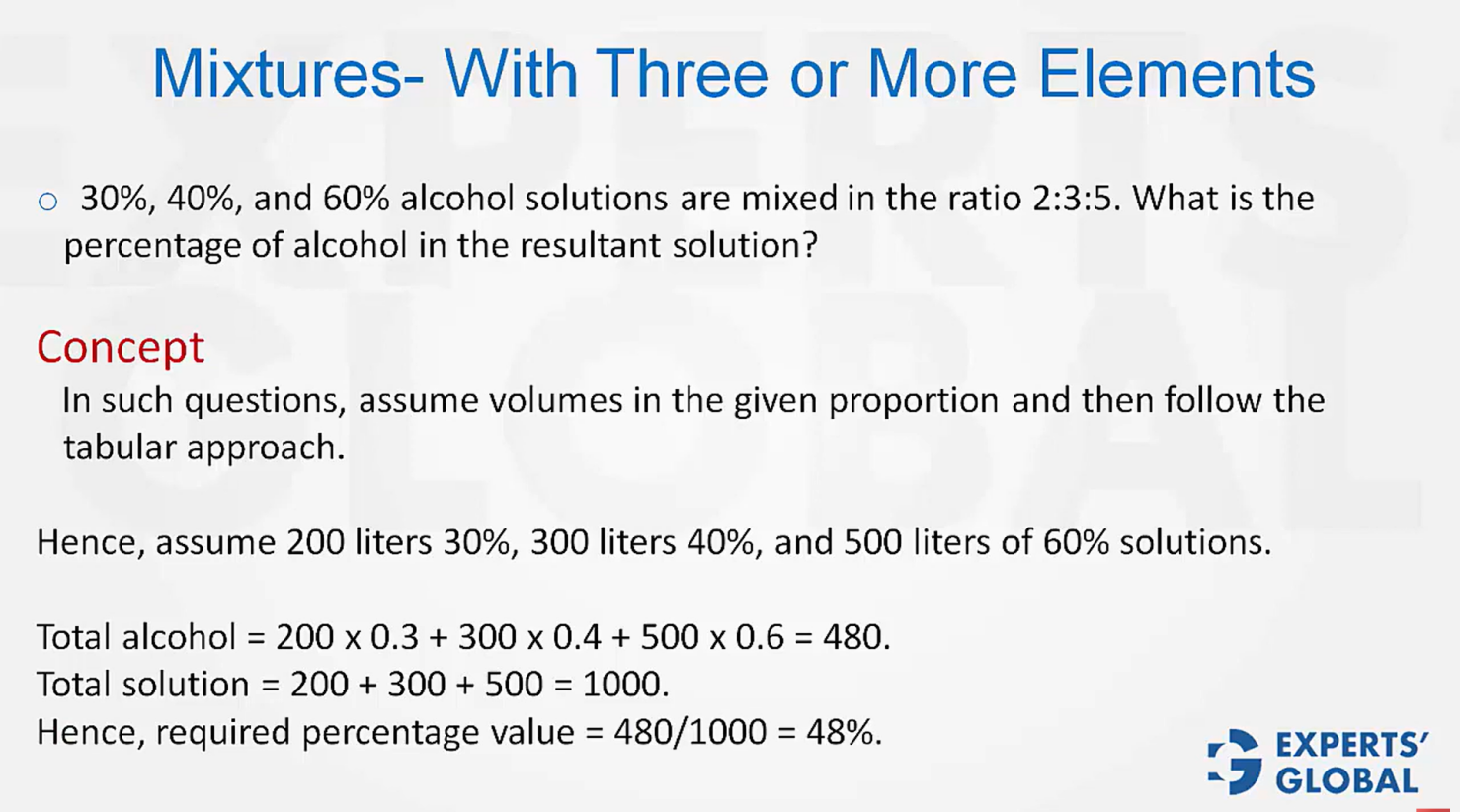

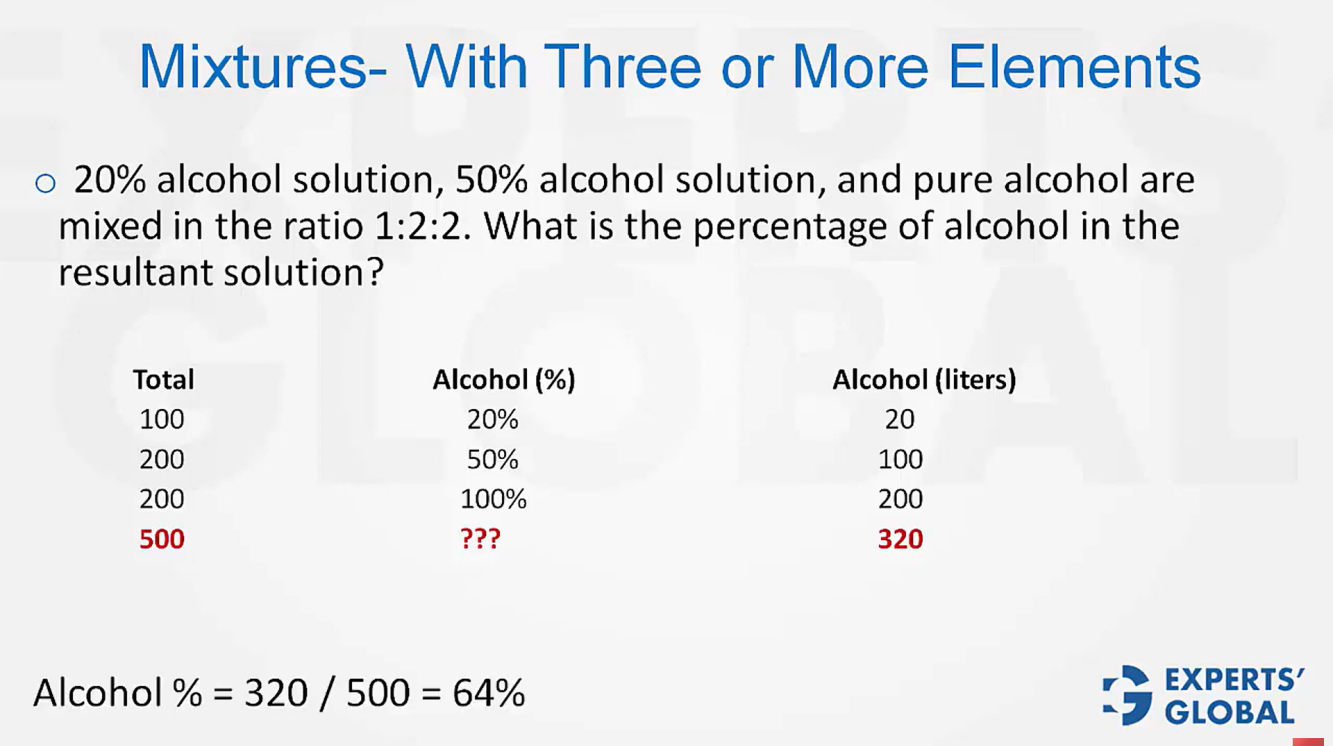

Mixture and ratio based solution questions often seem easy at first, yet they can quickly confuse students who approach them without a clear structure. The safest method is to assume convenient numbers for the given ratios and then use a simple table to track total volume, alcohol content, and water content. This practice reduces errors and keeps each step transparent. For instance, when three solutions are mixed in the ratio 2:3:5, it helps to assume volumes of 200, 300, and 500 liters respectively. Once these values are fixed, applying the given percentage concentrations becomes straightforward, and the absolute amounts of alcohol can be calculated. Adding these quantities and dividing by the total volume gives the overall concentration directly. In this way, such problems train you to handle ratios, percentages, and weighted averages in a calm, structured manner. The following short video makes this idea easy to follow and shows the ways in which it can be tested on the GMAT.

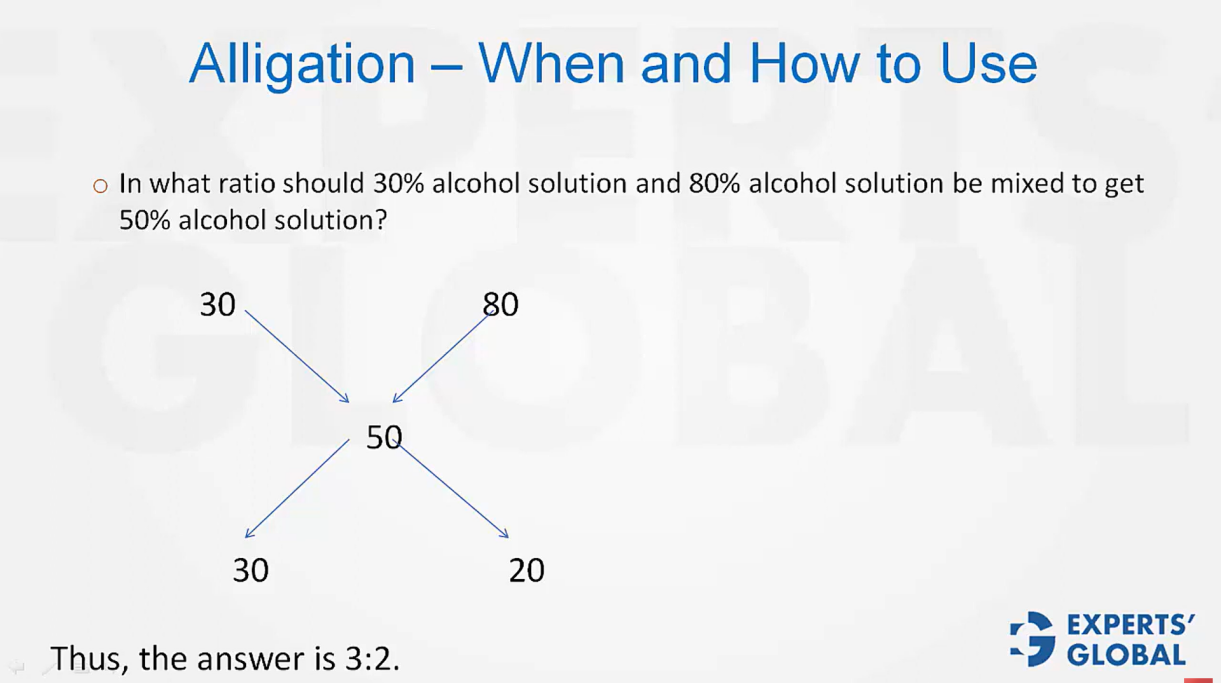

Many students feel confident with weighted average problems on mixtures but begin to struggle when the question is turned around: instead of asking for the final concentration, it asks in what ratio two components must be combined to reach a desired concentration. This is exactly where the idea of alligation becomes powerful. Alligation is a structured technique that removes the need for trial and error. It lets you place the two given concentrations and the target concentration in a simple layout, take the differences, and move directly to the required mixing ratio. For instance, if a 30% solution and an 80% solution are to be blended to create a 50% solution, alligation shows the ratio as 3:2 almost instantly, without long calculations. Questions of this type assess not only your arithmetic but also the clarity and discipline of your method. The brief video that follows lays out this idea clearly and shows how it might be tested on the GMAT.

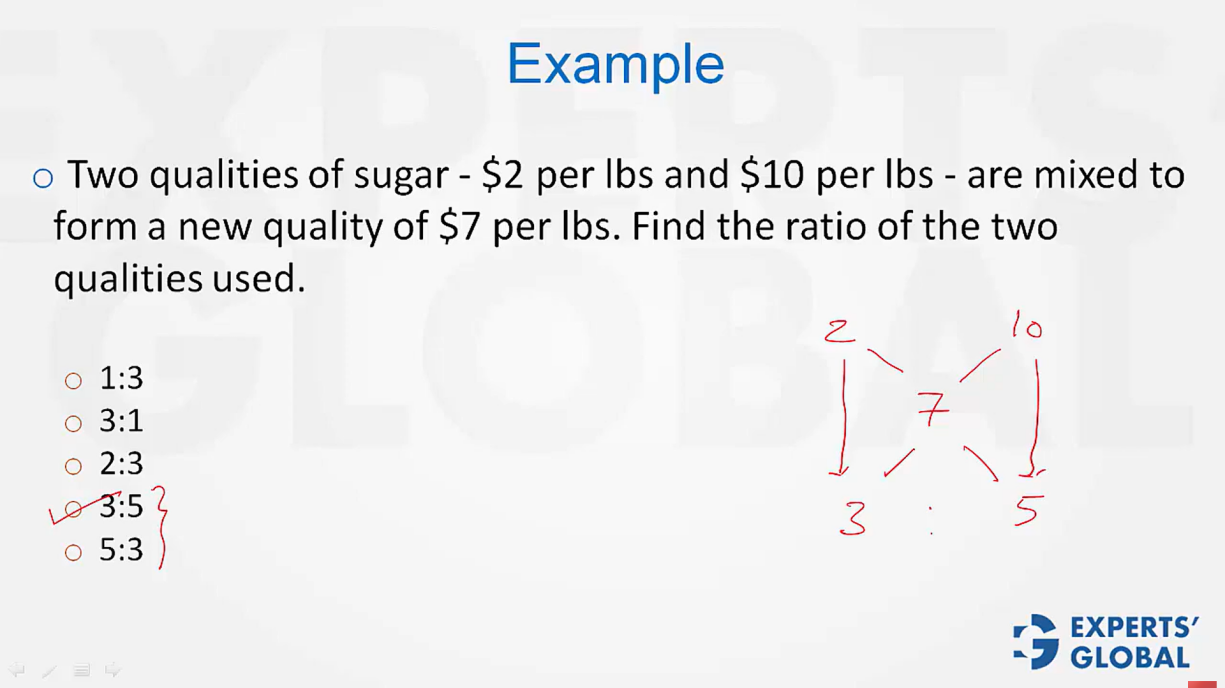

When mixture questions appear, many students spend extra time wrestling with percentages and ratios. In reality, there is a neat and graceful shortcut known as the rule of alligation. This technique lets you find the required ratio at once when two different strengths are blended to obtain a specific final strength. The idea is simple: place the two given values on either side, write the desired value in between, and then take the diagonal differences. These differences directly provide the ratio of the two components. For instance, if the original values are 2 and 10 and the target is 7, the differences are 5 and 3, which give the ratio 3:5. Approaching problems in this way brings clarity and helps you avoid careless slips, especially when the pressure of the exam is high. The short video below breaks this idea down and demonstrates how it can show up on the GMAT.

This segment features a focused set of GMAT-style Percentages, Mixtures, and Alligation questions, each accompanied by a clear, stepwise explanation. Work through every problem unhurriedly and consciously apply the methods and ideas you have just studied on this page for handling such questions on the GMAT. At this stage, your main goal is to use the outlined strategy correctly rather than to simply arrive at the right answer. After completing each question, open the explanation panel to check the correct response and review the reasoning in a detailed, descriptive form.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

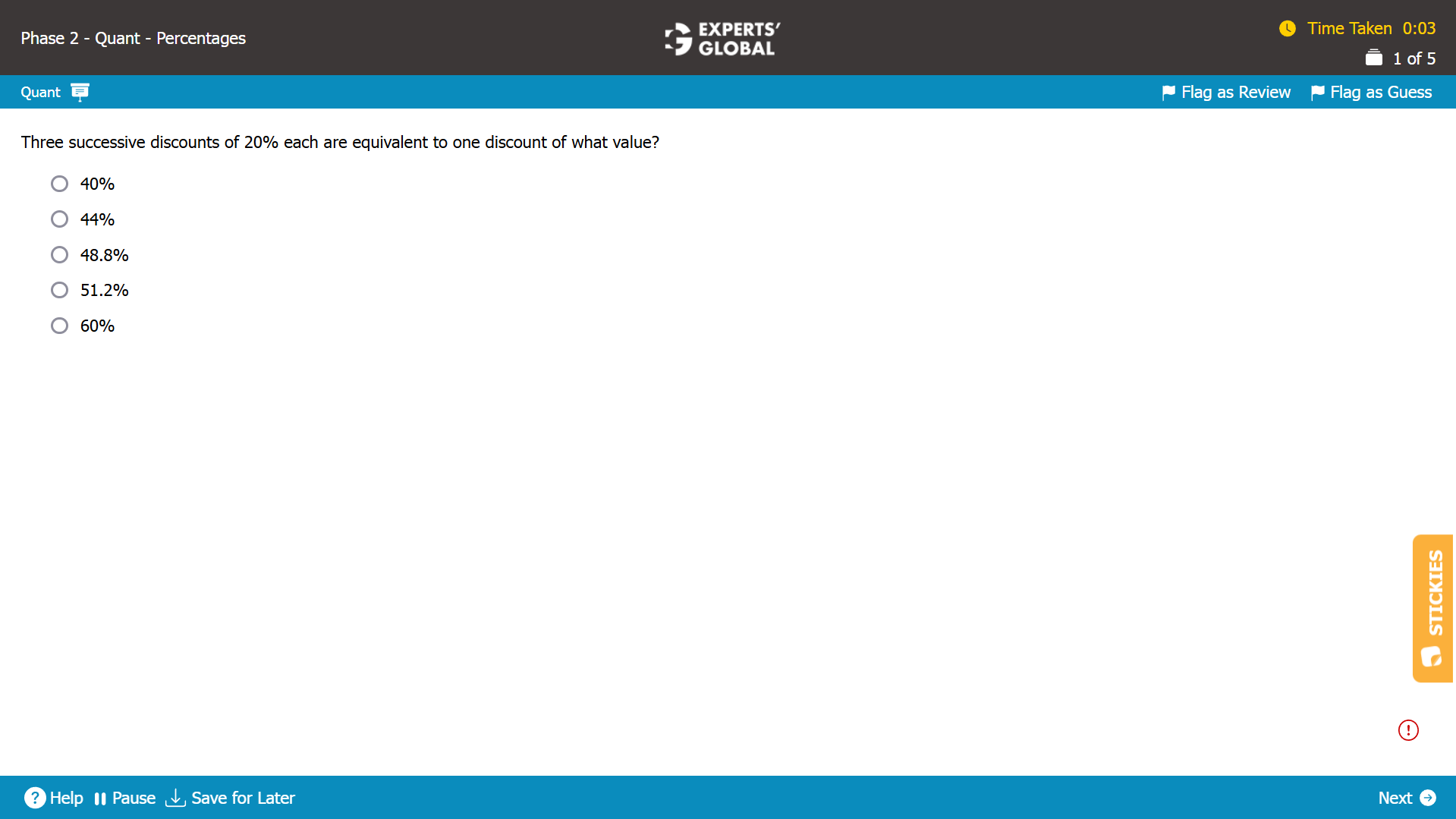

Let’s say the price is 100x before any discount.

After the first discount of 20%, the price becomes 100x X (1 – 0.2) = 100x X 0.8 = 80x

After the second discount of 20%, the price becomes 80x X (1 – 0.2) = 80x X 0.8 = 64x

After the third discount of 20%, the price becomes 64x X (1 – 0.2) = 64x X 0.8 = 51.2x

From the original price of 100x, the price came down to 51.2x.

So, the total discount is (100x – 51.2x) / (100x) = 48.8x / 100x = 48.8%.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

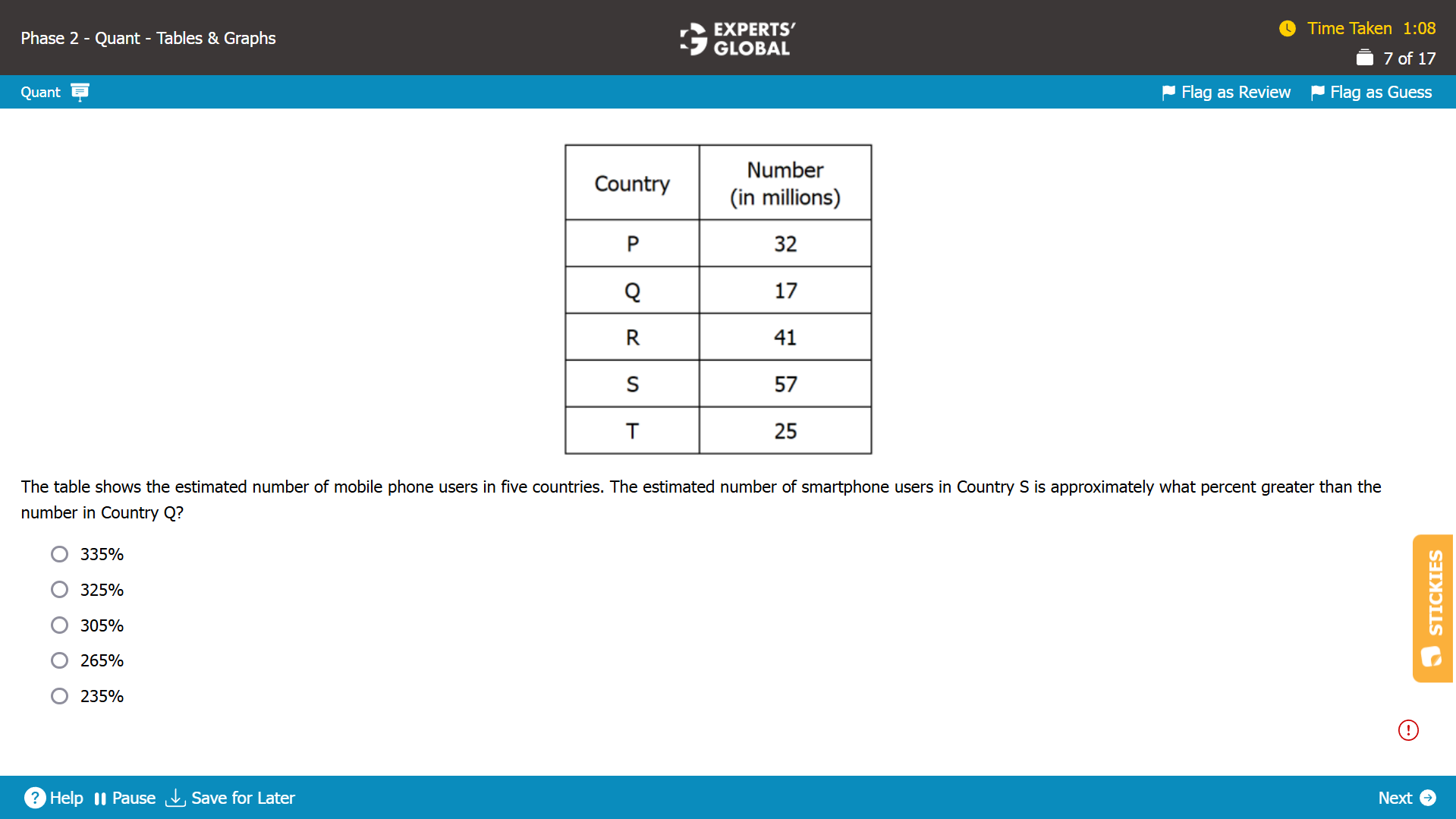

Let the estimated number of smartphone users in Country S be A.

Let the estimated number of smartphone users in Country Q be B.

We need to determine by what percent is A greater than B, which can also be expressed be as:

We need to determine the value of 100 × (A – B) / B .

Since the estimated number of smartphone users in Country S is 57 million, A = 57 million.

Since the estimated number of smartphone users in Country Q is 17 million, B = 17 million.

Thus, A – B = 57 – 17 = 40 million.

The required percentage = 100 × (A – B) / B = 100 × 40 / 17 = 235%

Hence, the estimated number of smartphone users in Country S is approximately 235% percent greater than the number in Country Q.

E is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

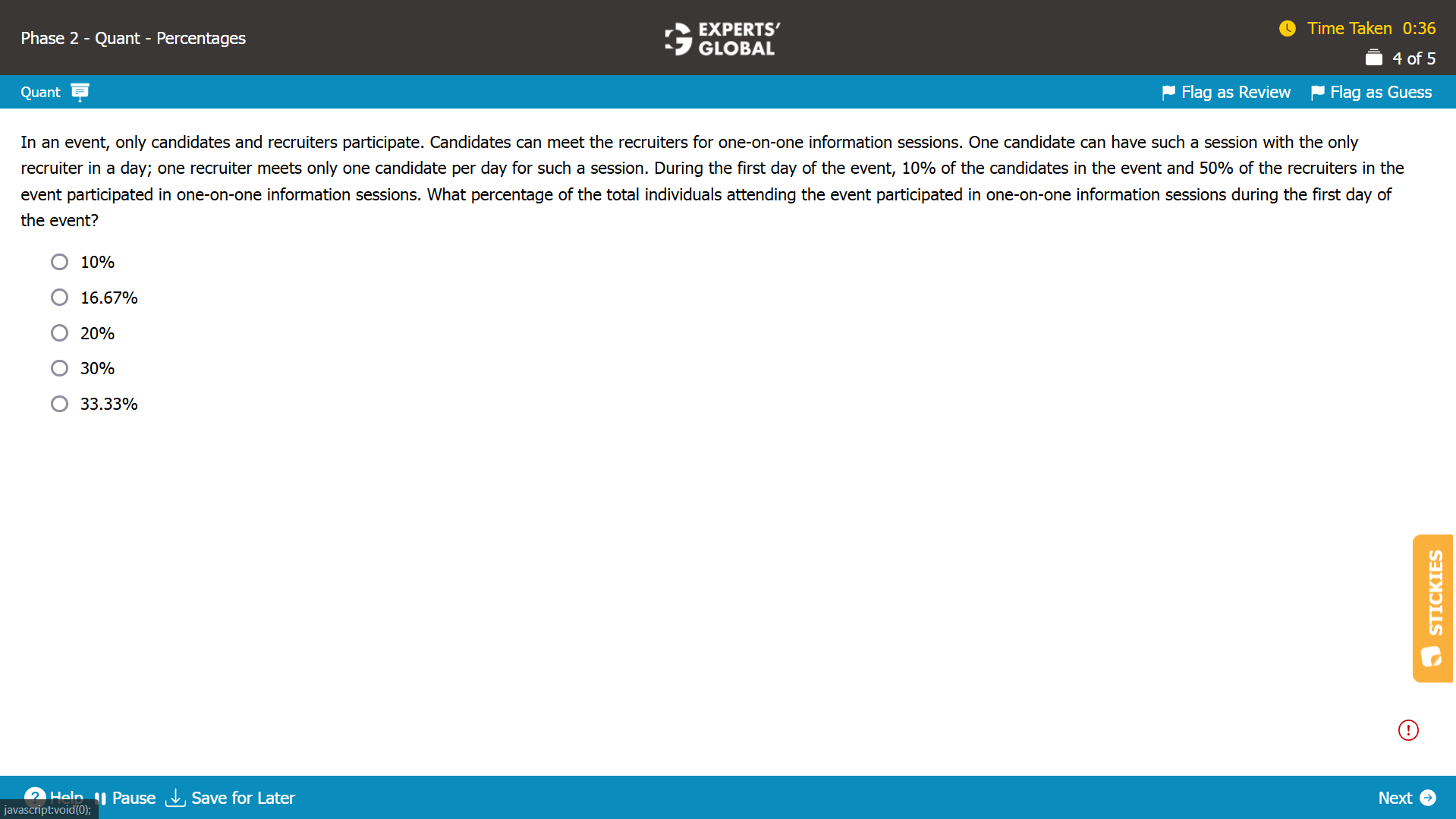

Let’s say that there were x number of one-on-one information sessions. Each session has one recruiter and one candidate. So, x candidates participated in the sessions and x recruiters participated in the sessions.

Number of individuals that participated in one-on-one information sessions = x candidates + x recruiters = 2x

10% of all candidates participated. So, 10% of all candidates = x; Number of all candidates = 10x.

50% of all recruiters participated. So, 50% of all recruiters = x; Number of all recruiters = 2x.

Total number of individuals = number of all candidates + number of all recruiters = 10x + 2x = 12x.

Percentage of total individuals that participated in one-on-one information sessions = (2x / 12x) X 100 = 16.67%.

B is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

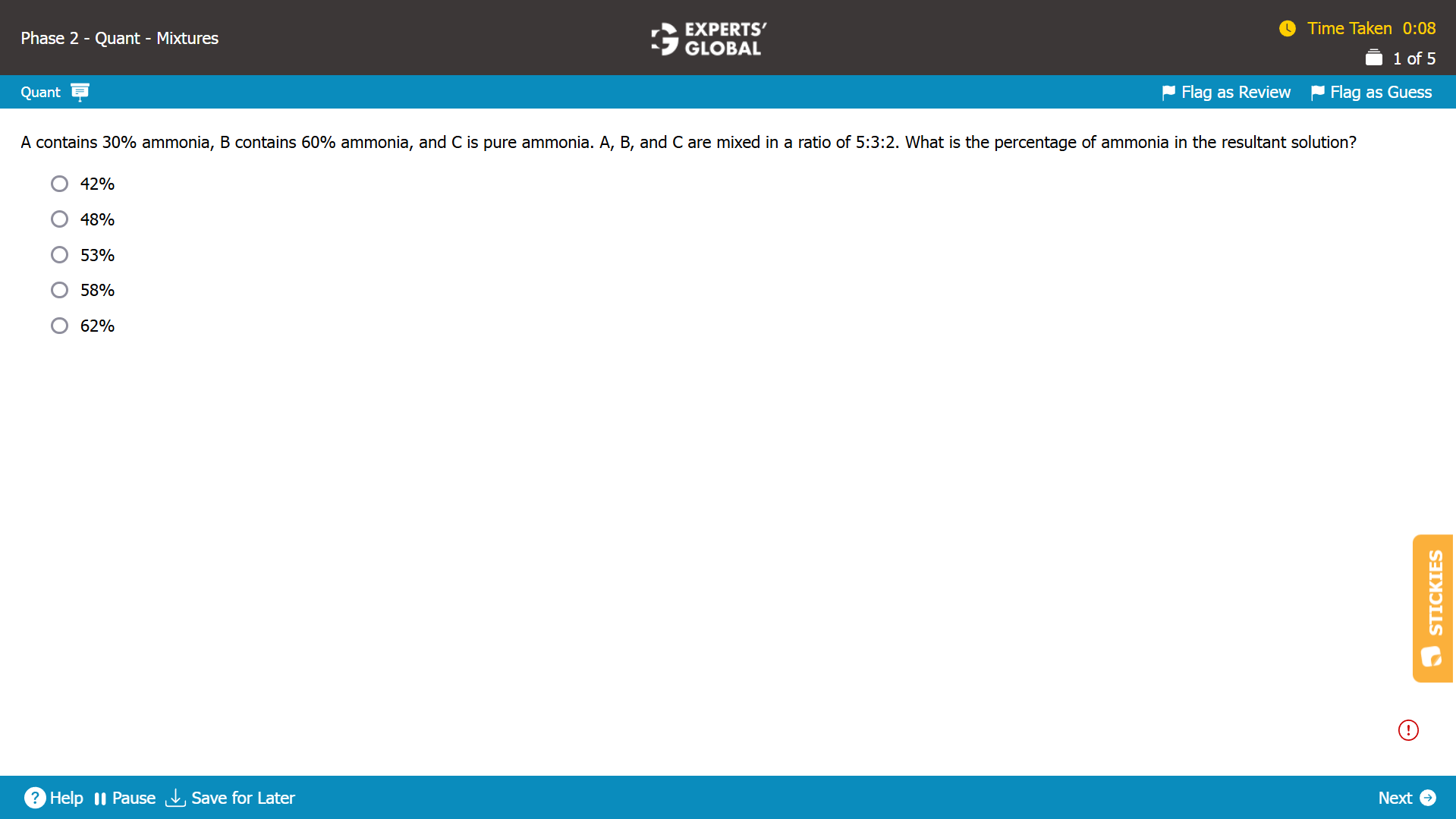

A, B, and C are mixed in a ratio of 5:3:2.

Let’s say that 5x liters of A is mixed with 3x liters of B and 2x liters of C.

A contains 30% ammonia.

So, the quantity of ammonia in A = 30% of 5x = 1.5x liters.

B contains 60% ammonia.

So, the quantity of ammonia in B = 60% of 3x = 1.8x liters.

C contains pure ammonia; in other words, C contains 100% ammonia.

So, the quantity of ammonia in C = 2x.

Total quantity of resultant solution = 5x + 3x + 2x = 10x.

Total quantity of ammonia in the resultant solution = 1.5x + 1.8x + 2x = 5.3x.

Percentage of ammonia in the resultant solution = 5.3x / 10x = 53%.

The resultant solution contains 53% ammonia.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

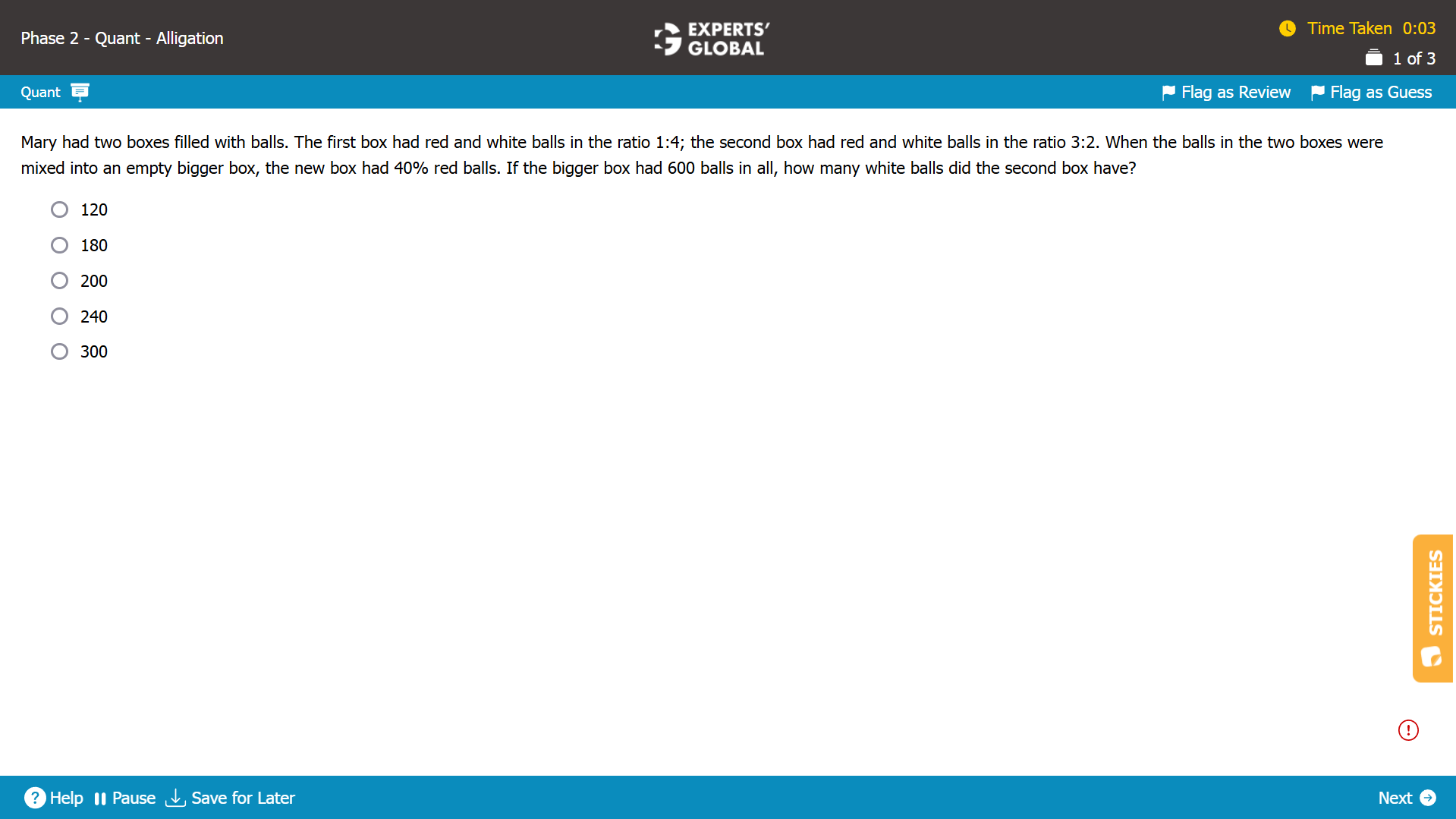

Ratio of red and white balls in the first box = 1:4

So, let’s say that the first box had x red balls and 4x white balls.

Total number balls in the first box = 5x balls.

Ratio of red and white balls in the second box = 3:2

So, let’s say that the first box had 3y red balls and 2y white balls.

Total number balls in the second box = 5y balls.

When the two boxes are mixed into a new, bigger box,

Total number of balls in the biggest box = 600 = 5x + 5y

So, (x + y) = 120 … (Equation I)

The biggest box had 40% red balls.

So, number of red balls in the biggest box = 40% of 600 balls = 240 balls … (Equation II)

Also…

Number of red balls in the biggest box = number of red balls in the first box + number of red balls in the second box = x + 3y… (Equation III)

Equating Equation II and Equation III…

x + 3y = 240

x = 240 – 3y

Substituting x = 240 – 3y in Equation I….

(240 – 3y) + y = 120

2y = 120

y = 60

Number of white balls in the second box = 2y = 120 balls.

Please watch the video for an alternate method to solve.

A is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

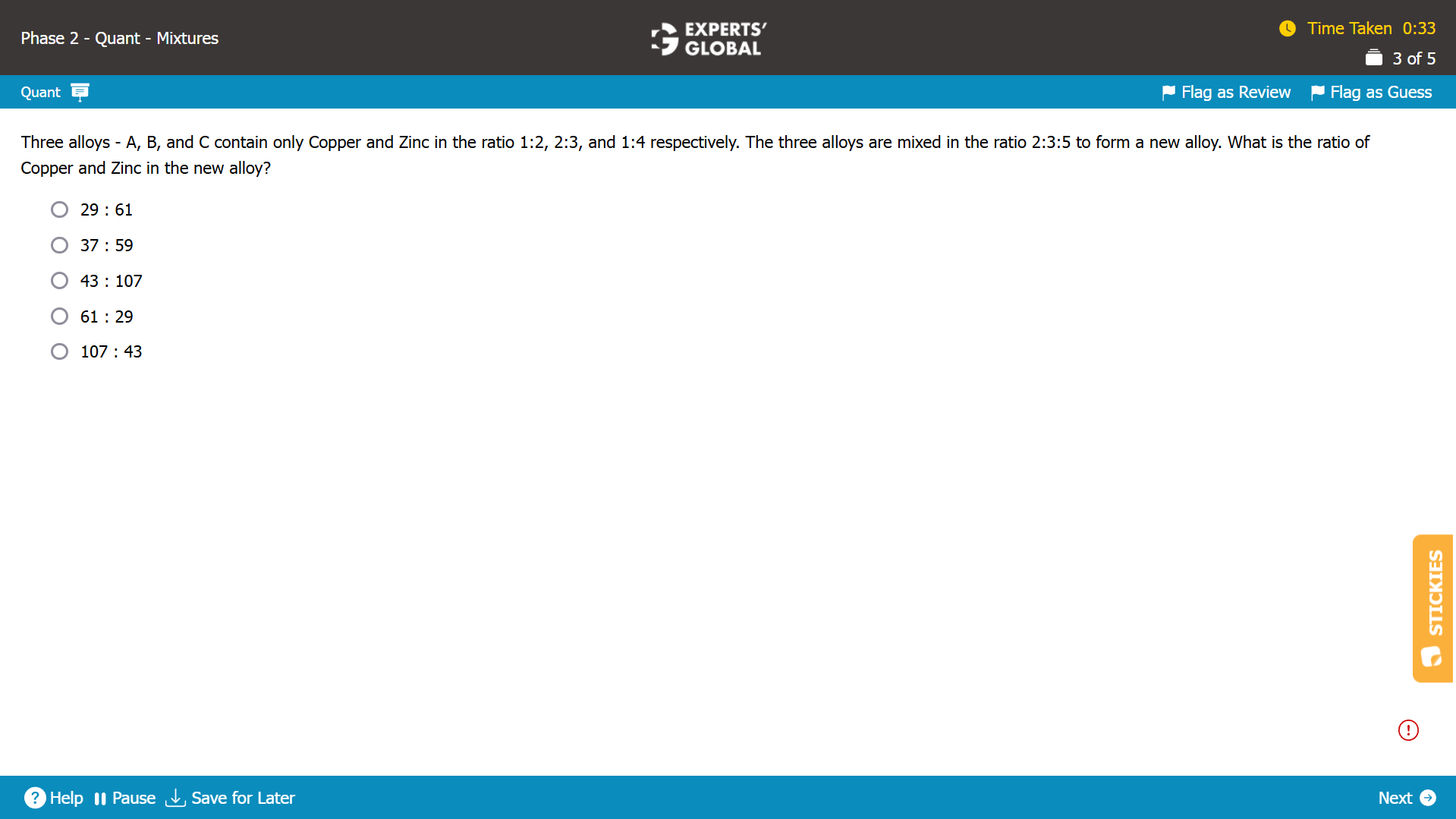

The three alloys – A, B, C – are mixed in the ratio 2:3:5.

So, let’s say that the 30x units of A is mixed with 45x units of B and 75x units of C.

Copper: Zinc in alloy A = 1 : 2

Total quantity of A = 30x units

Quantity of Copper in A = (1 / (1 + 2)) X 30x = 10x units

Quantity of Zinc in A = (2 / (1 + 2)) X 30x = 20x units

Copper: Zinc in alloy B = 2 : 3

Total quantity of B = 45x units

Quantity of Copper in B = (2 / (2 + 3)) X 45x = 18x units

Quantity of Zinc in B = (3 / (2 + 3)) X 45x = 27x units

Copper: Zinc in alloy C = 1 : 4

Total quantity of B = 75x units

Quantity of Copper in B = (1 / (1 + 4)) X 75x = 15x units

Quantity of Zinc in B = (4 / (1 + 4)) X 75x = 60x units

Quantity of new alloy = 30x + 45x + 75x = 150x units

Quantity of Copper in new alloy = 10x + 18x + 15x = 43x units

Quantity of Zinc in new alloy = 20x + 27x + 60x = 107x units

The ratio of Copper and Zinc in the new alloy = 43x : 107x = 43 : 107.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

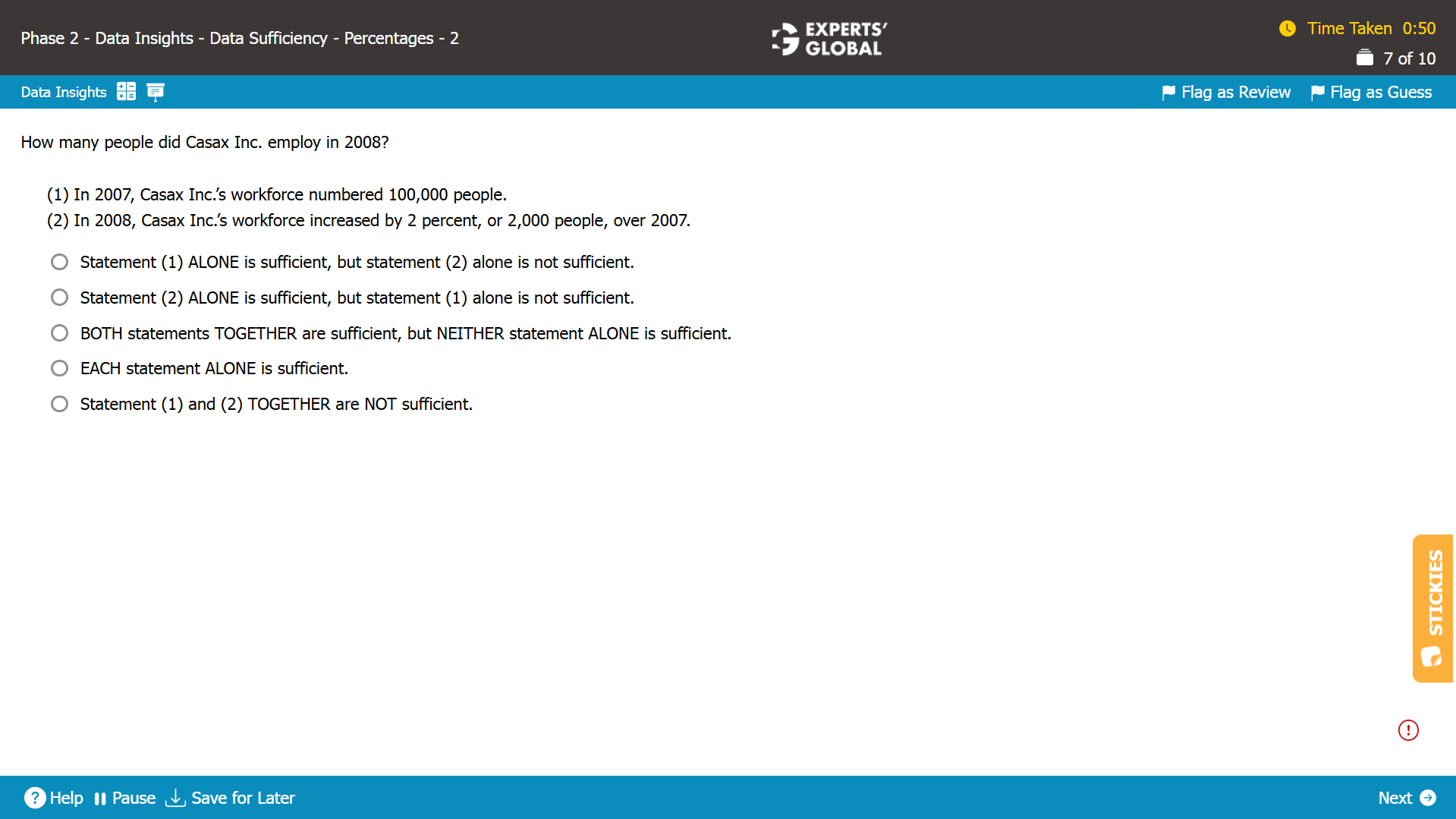

Let the number of employees in 2007 be A.

Let the number of employees in 2008 be B.

We need to find whether the value of B can be determined.

Statement (1)

A = 100,000

Since no information is provided regarding the relation between A and B, it is NOT possible to determine the exact value of B. Hence, Statement (1) is insufficient.

Statement (2)

Casax Inc.’s workforce increased by 2 percent, which can be expressed as: B = 1.02A

Casax Inc.’s workforce increased by 2000, which can be expressed as: B = 2000 + A

Since we have 2 equations with 2 unknown variables, it is possible to determine the exact value of B. Hence, Statement (2) is sufficient.

B is the correct answer choice.

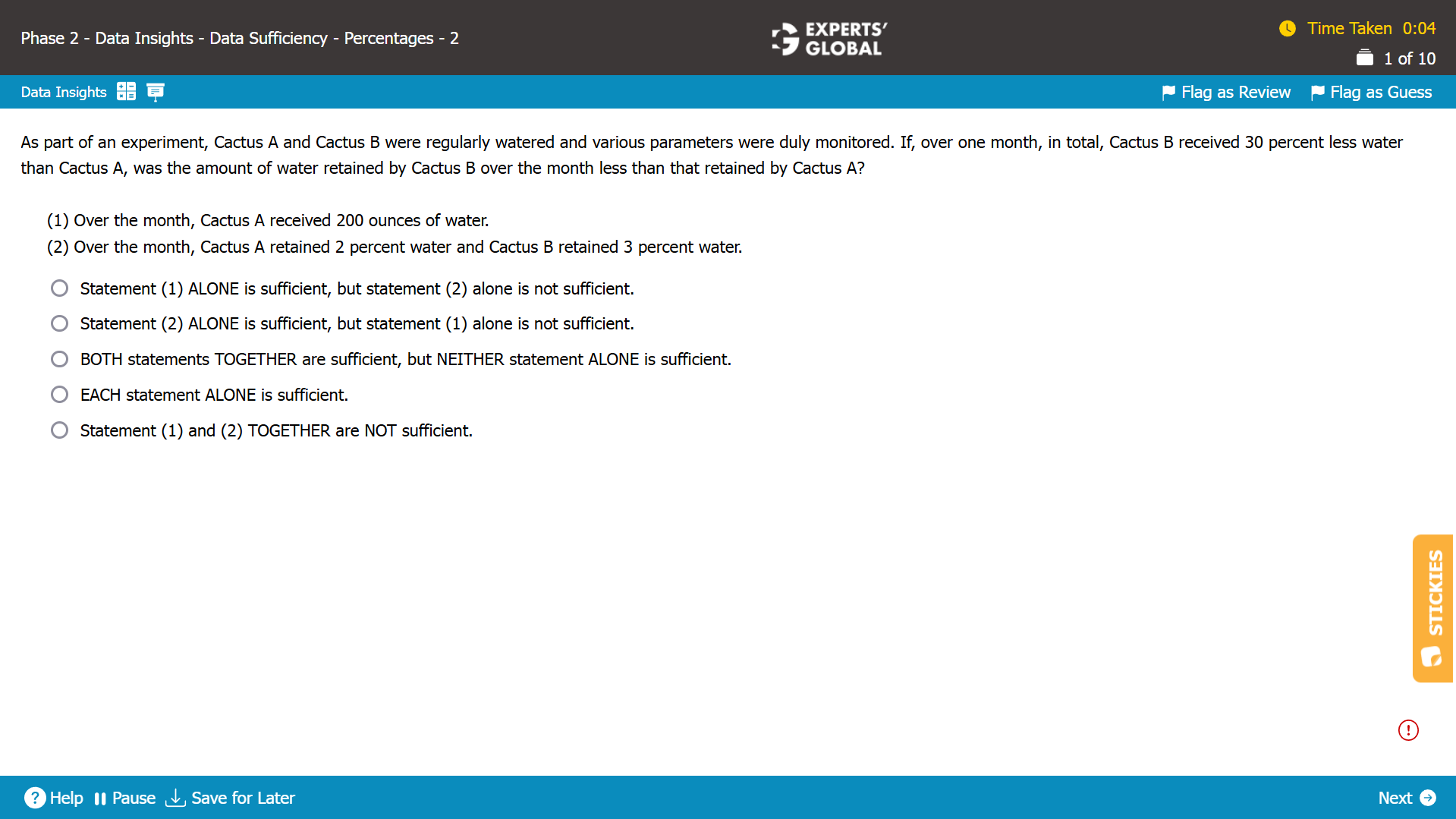

Show Explanation

Let the total amount of water received by Cactus A be X.

Let the total amount of water received by Cactus B be Y.

Let the amount of water retained by Cactus A be P.

Let the amount of water retained by Cactus B be Q.

Since Cactus B received 30 percent less water than Cactus A: Y = 0.7X (Equation I)

We need to find whether Q < P.

Statement (1)

X = 200

Since no information is provided regarding the values of Q and P, it is NOT possible to determine with certainty whether Q < P. Hence, Statement (1) is insufficient.

Statement (2)

P = 0.02X

Q = 0.03Y (Equation II)

From Equations I and II, Q = 0.03Y = 0.03(0.7X) = 0.021X > 0.02X = P

It is possible to determine with certainty that Q > P. Hence, Statement (2) is sufficient.

B is the correct answer choice.

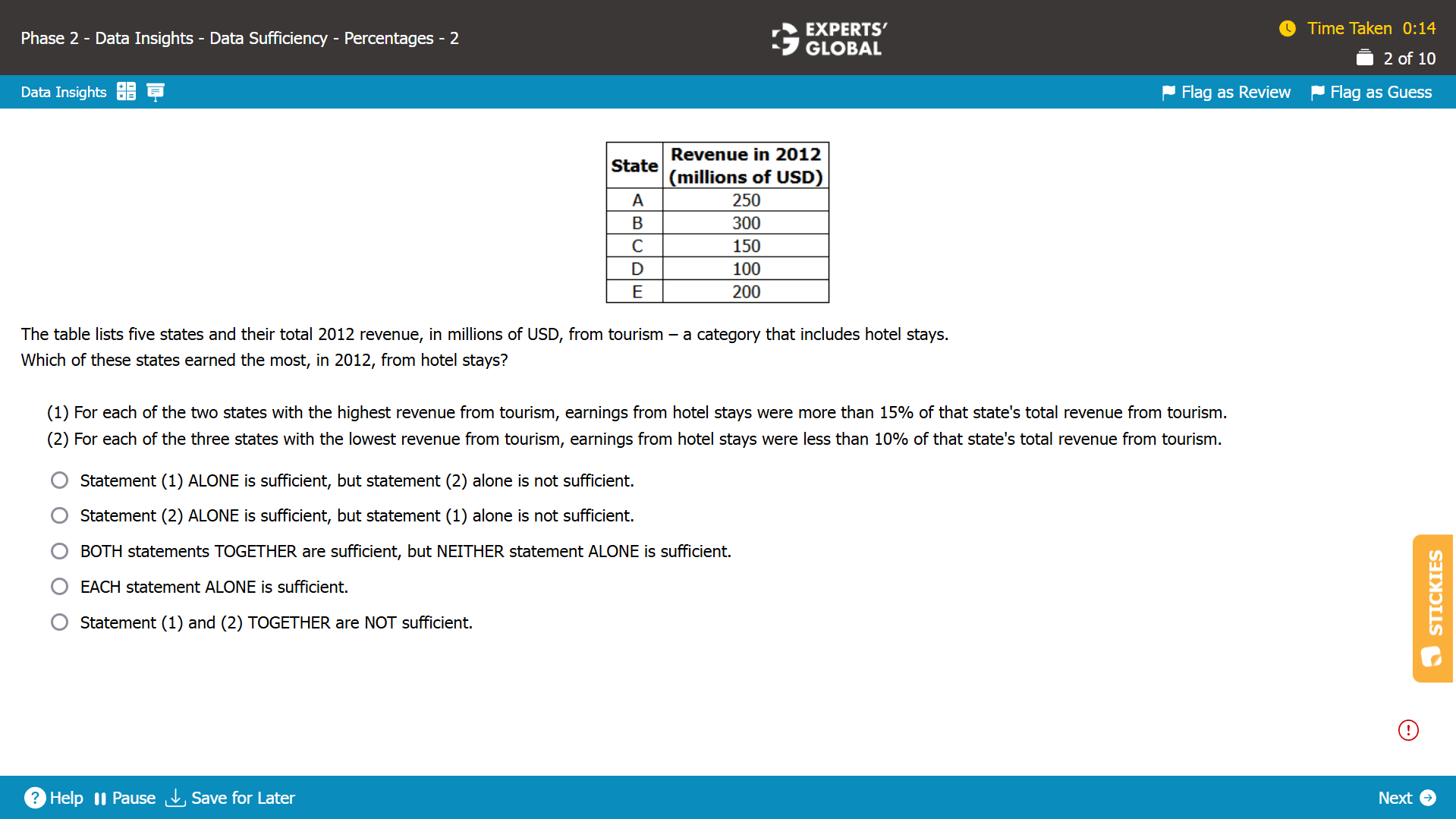

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

Statement (1)

A contains 20% alcohol, B contains 20% alcohol, and C contains 80% water.

Whether solution C contains only water and alcohol is not known.

The ratio of alcohol and water in the resultant solution cannot be determined. Insufficient.

Statement (2)

All solutions contain only water and alcohol.

Nothing is known about the ratio of alcohol and water in any solution.

Nothing is known about the ratio in which the three solutions are mixed.

The ratio of alcohol and water in the resultant solution cannot be determined. Insufficient.

Because both the statements alone are not sufficient, let’s combine the two statements.

Statement (1) and Statement (2) combined

A contains 20% alcohol, B contains 20% alcohol, and C contains 80% water.

All solutions contain only water and alcohol.

So, solution C contains 100 – 80 = 20% alcohol.

Overall, all three solutions contain 20% alcohol.

Regardless of the ratio in which the three solutions are mixed, the resultant solution will have 20% alcohol.

The ratio of alcohol and water in the resultant solution can be determined. Sufficient.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

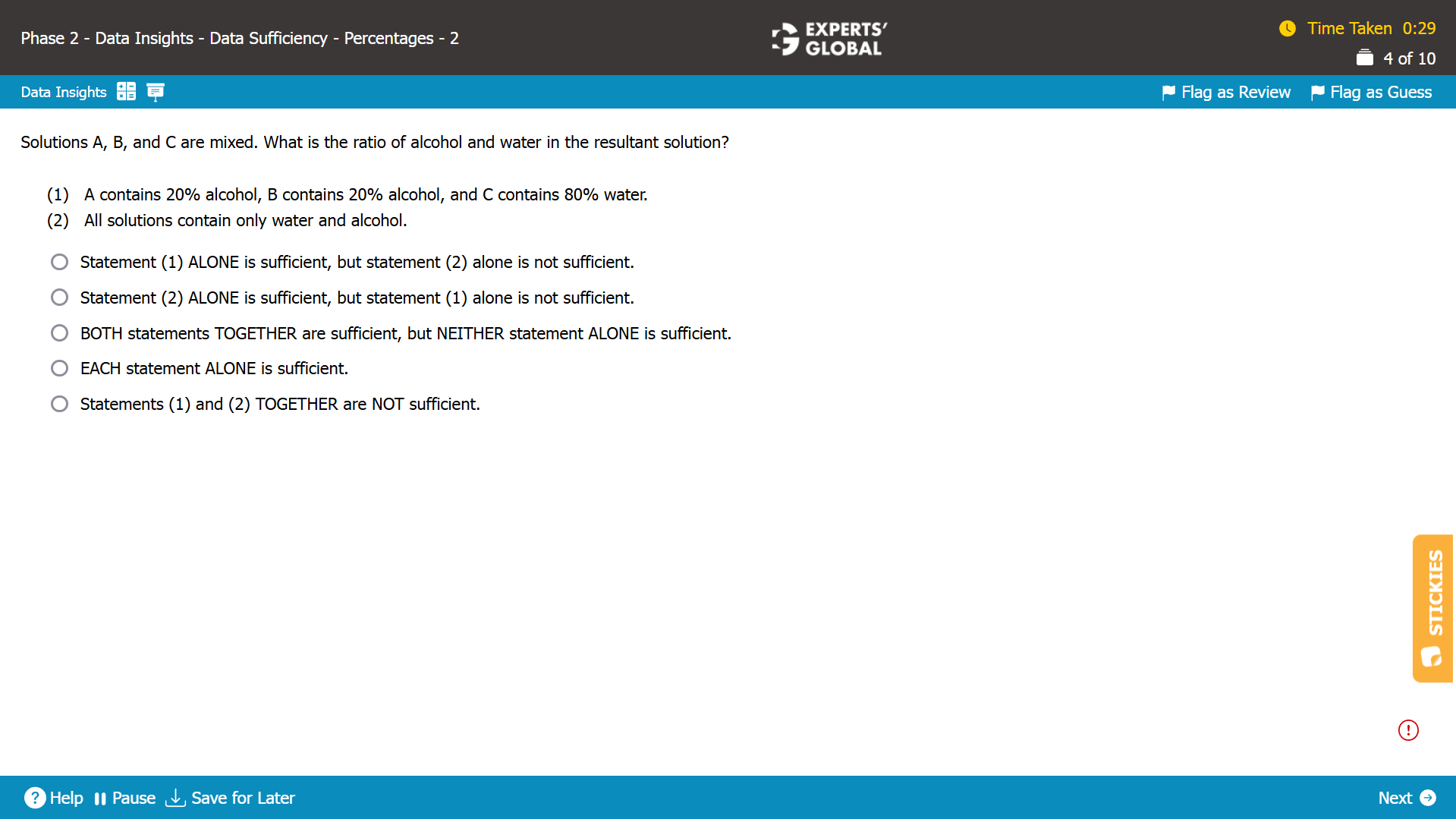

The table shows the revenue from tourism for five states.

The earnings from hotel stays for each of the five states are unknown.

We need to find whether the state with the highest earnings from hotel stays can be determined.

Statement (1)

The two states with the highest revenue from tourism are state A and state B.

Earnings from hotel stays for state A > 0.15 × 250

Earnings from hotel stays for state B > 0.15 × 300

The earnings from hotel stays for either state A or state B could be higher based on the given condition.

It is NOT possible to determine the state with the highest earnings from hotel stays. Hence, Statement (1) is insufficient.

Statement (2)

The three states with the lowest revenue from tourism are state C, state D, and state E.

Earnings from hotel stays for state C < 0.1 × 150

Earnings from hotel stays for state D < 0.1 × 100

Earnings from hotel stays for state E < 0.1 × 200

Since no information is provided regarding two of the states with the highest revenue, it is NOT possible to determine the state with the highest earnings from hotel stays. Hence, Statement (2) is insufficient.

As Statement (1) alone as well as Statement (2) alone is insufficient to answer the question, we need to now combine the two statements.

Statement (1) and Statement (2) combined

The two statements combined give us no additional information about the earnings from hotel stays for either state A or state B.

It is NOT possible to determine the state with the highest earnings from hotel stays. Hence, Statement (1) and Statement (2) combined are insufficient.

E is the correct answer choice.

Real practice for Percentages, Mixtures, and Alligation problems begins when you work on a software simulation that closely matches the official GMAT interface. You need a platform that shows these word and calculation based questions in a GMAT like layout, lets you engage with the information and answer choices naturally, and provides all the on screen tools and functionalities that you will see on the actual exam. Without this kind of environment, it is difficult to feel fully prepared for test day. High quality Percentages, Mixtures, and Alligation questions are not available in large numbers. Among the limited, genuinely strong sources are the official practice materials released by GMAC and the Experts’ Global GMAT course.

Within the Experts’ Global GMAT online preparation course, every Percentages, Mixtures, and Alligation problem appears on an exact GMAT like user interface that includes all the real exam tools and features. You work through more than 100 such questions in quizzes and also take 15 full-length GMAT mock tests that include several Percentages, Mixtures, and Alligation questions in roughly the same spread and proportion in which they appear on the actual GMAT.

All the best!