Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Permutations describe the number of ways to arrange items when order matters, while combinations describe the number of ways to select items when order does not matter. Together, they help us understand structured counting in a clear and logical way. Careful treatment of these concepts is an essential part of any comprehensive GMAT prep course. This page offers you an organized subtopic wise playlist, along with a few worked examples, for efficient combinatorics preparation.

When you face counting problems, many students either make simple mistakes or complicate the task by trying to apply formulas directly instead of relying on clear reasoning. The intention should be to think step by step, ask how many choices exist at each stage, and then multiply these choices together. This way of thinking works whether you are arranging people in seats, selecting items, or dealing with independent events. Consider a straightforward case. If 10 boys are to be seated in a row of 10 chairs, the first boy has 10 options, the second has 9, the third has 8, and so on until the last boy has only 1 option. This results in 10 factorial, written as 10!, total arrangements. The same idea extends naturally to more complex situations, such as partial arrangements or problems with several independent outcomes. For deeper learning, explore our GMAT preparation course and strengthen these skills through focused GMAT diagnostic tests. This short video explains the method, shows it solving representative questions, and equips you to apply it in GMAT drills, sectional tests, and full-length GMAT mock tests.

Many students mix up permutations and combinations, often applying the wrong idea in GMAT questions. The crucial difference lies in whether the order of arrangement matters. When order is important, you are dealing with permutations. When order does not matter, you use combinations. This simple distinction changes the entire method, and missing it can lead to serious mistakes. For example, arranging students in a row is a permutations scenario because the sequence of students matters. In contrast, selecting a group of students for a project team is a combinations case because the order of selection is irrelevant. Grasping this idea is vital for mastering GMAT Quantitative Reasoning, and regular practice with such problems steadily builds confidence. The short video below explains this idea in an intuitive way and demonstrates how it may appear on the GMAT.

Many students feel uncertain about when to use permutations and when to use combinations. The formulas may seem alike, but the thinking behind them is quite different. The core idea is to check whether order matters. If order matters, you are dealing with permutations; if order does not matter, it is a combination. To understand this deeply, it helps to explore everyday examples, such as lining children up in a row or choosing a team from a larger group. Each situation follows a clear logic that guides you toward using nPr or nCr. Mastering this distinction during your GMAT prep not only sharpens accuracy but also saves valuable time on the test. The following short video breaks this concept into simple steps and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT. The brief video that follows clarifies this idea with examples and shows how the GMAT can test it.

Many GMAT aspirants feel unsure about when to use permutations and when to use combinations. The difference may seem small, yet it completely changes how you handle a question. The first guiding step is to ask whether the sequence of choices matters. If order matters, then you are dealing with permutations. If order does not matter, you are working with combinations. This single distinction decides whether you count every arrangement separately or remove repeated orders from the total. For instance, seating children in a row is about arranging, while choosing a team is about selecting. With this clarity in place, even large problems with many elements can be approached in a calm, systematic way. The short video below presents this idea in a calm, clear manner and illustrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Permutations and combinations are closely related concepts in counting. A combination deals with choosing items when the order of choice is irrelevant, while a permutation builds on that idea by counting the different ways those chosen items can be arranged. Seeing this connection is an important part of GMAT preparation, because it explains how one concept naturally leads to the other and why their formulas are linked. For instance, choosing a group illustrates combinations, and then arranging that same group in different sequences illustrates permutations. The following short video offers a neat explanation of this idea and shows how it can show up on the GMAT.

Permutations and combinations become truly clear when you watch them unfold across different types of situations. A single setup can split into several possibilities, each shaped by its own set of restrictions or groupings. In the explanatory video that supports this article, followed by the written walkthrough, we examine eight engaging scenarios that show how outcomes shift as the conditions change. Exploring such variations is an important part of a focused GMAT prep course, as it deepens conceptual understanding and sharpens logical precision. The brief video that follows helps you internalize this concept and demonstrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Combinations lie at the heart of many counting problems because they describe situations in which order does not matter. This article, together with the explanatory video, walks through eight carefully chosen examples that show how fine details such as inclusions, exclusions, or minimum requirements can change the final count in meaningful ways. Viewing these cases side by side reveals the true logic behind combinatorics and clarifies when complementary counting or dividing into cases offers a cleaner path. Working through such patterns is a core element of thoughtful GMAT preparation, since clarity of structure directly leads to better accuracy. The short video below explains this idea in a friendly way and shows how the GMAT may test it.

Circular arrangements form a special category within permutation problems because what matters is how people are placed relative to one another, not their absolute positions. Unlike linear seating, rotating the entire circle does not create a new arrangement, which is why the number of distinct seatings is given by (n − 1)!. In the explanatory video that accompanies this article, followed by the written discussion, we delve into several thoughtful variations built on this idea, including cases where certain people sit together, where some must or must not sit side by side, and how the presence of numbered seats changes the counting. The following short video walks through this concept carefully and illustrates how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Multiset permutations, or repetitive arrangements, arise when some elements are identical while others are different, making the counting more delicate than in basic permutation cases. Rather than treating each item as distinct, you must adjust for repetition so that you do not overcount. The explanatory video and the accompanying discussion examine examples such as arranging colored balls in given quantities and forming words that contain repeated letters, each showing how the interplay between distinct and identical elements changes the final count. Growing comfortable with these patterns sharpens logical accuracy and makes your problem solving more efficient. The brief video that follows sheds light on this idea and shows how it can appear in GMAT problems.

Distributive arrangements in combinatorics examine how objects can be shared among different groups, with the method changing based on whether the items are distinct or identical and whether any restrictions are in place. This article, together with the accompanying video, presents classic patterns such as distributing distinct objects among recipients using multiplication, dividing identical objects through the “stars and bars” idea, and adjusting the count when conditions like “no group left empty” are introduced. The emphasis is not on memorizing final answers but on recognizing which method suits each specific situation. The following short video makes this idea feel natural and demonstrates how the GMAT can test it.

This article, together with its supporting video, explores two high difficulty examples of distributive arrangement problems, a theme that appears often in combinatorics. These illustrations deal with sharing objects among groups under strict conditions, showing how slight changes in requirements can significantly reshape the counting process. The goal is not to burden you with formulas, but to bring out the logic and structure that let you handle such questions step by step. By studying cases where, for instance, every participant must receive at least one item, you develop a deeper feel for the many variations and twists that can arise. The brief video that follows explains this idea without fuss and shows how it can be tested on the GMAT.

Teaming questions in combinatorics examine how smaller groups are created from a larger pool, with the real challenge lying in whether the teams are considered identical or distinct. When teams are identical in size and status, extra care is required to adjust for overcounting. When teams differ in size or are assigned specific roles, every distinct assignment becomes a separate arrangement. These subtle shifts call for thoughtful reasoning and show clearly why simple factorials alone do not always give the correct answer. The short video below turns this idea into something very manageable and shows how it may appear on the GMAT.

Derangements are special permutations in which no element occupies its original position, and they form an important idea in combinatorics. This article, along with the accompanying video, develops the concept through carefully structured examples, starting with four letters and four envelopes and examining every possible situation. From seeing why three correct matches cannot occur to finding the exact values of D(n) for small n, the explanation builds understanding step by step. Once the intuition is clear, the general formula is introduced, followed by applications in which some elements remain fixed while the rest are deranged. The following short video deepens your understanding of this concept and shows how it is tested on the GMAT.

Here you will find a focused set of GMAT-style Permutations and Combinations questions, each paired with an in-depth, stepwise explanation. Move through every problem patiently and make a conscious effort to use the methods and ideas you have just studied on this page for solving Permutations and Combinations questions on the GMAT. At this stage, your priority is to apply the strategy carefully and consistently rather than to simply obtain the correct answer. Once you complete a question, open the explanation panel to view the right option and study the full descriptive reasoning.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

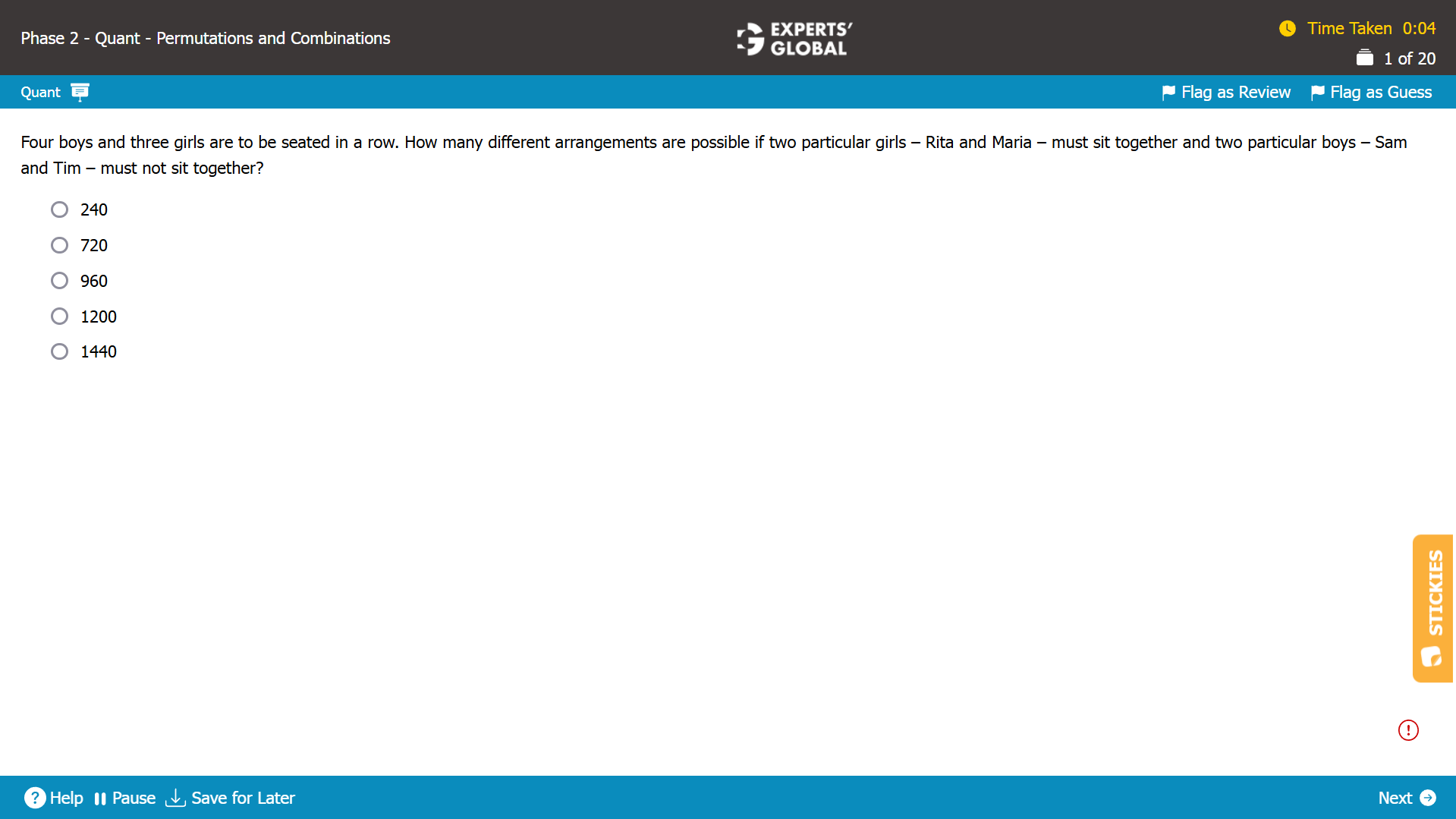

Four boys and three girls represent 4 + 3 = 7 units to be arranged.

Let’s consider the condition related to two girls.

Two girls must sit together. So, let’s consider them one unit.

Total number of units to be arranged = 7 – 1 = 6 units.

6 units can be arranged in 6! ways.

The two girls in the single unit can sit in 2! = 2 different ways – Rita-Maria, or Maria-Rita.

Total number of ways considering the condition of two girls = 6! X 2! … (Equation I)

Let’s consider the condition related to two boys.

Two boys must not sit together. So, let’s subtract the number of ways in which they do sit together.

Total number of ways considering the condition of two girls and two boys = (6! X 2!) – total number of ways in which the two boys do sit together … (Equation II)

If the two boys do sit together, let’s consider them one unit.

Total number of units to be arranged = one unit of two girls + one unit of two boys + three units of three individuals = 1 + 1 + 3 = 5

5 units can be arranged in 5! Ways.

The two girls in the single unit can sit in 2! = 2 different ways – Rita-Maria, or Maria-Rita.

Similarly, the two boys in the single unit can sit in 2! = 2 different ways – Sam-Tim, or Tim-Sam.

Total number of ways in which the two boys do sit together = 5! X 2! X 2! … (Equation III)

Substituting Equation III in Equation II…

Total number of ways considering the condition of two girls and two boys = (6! X 2!) – (5! X 2! X 2!) = 1440 – 480 = 960.

The required arrangement can be done in 960 ways.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

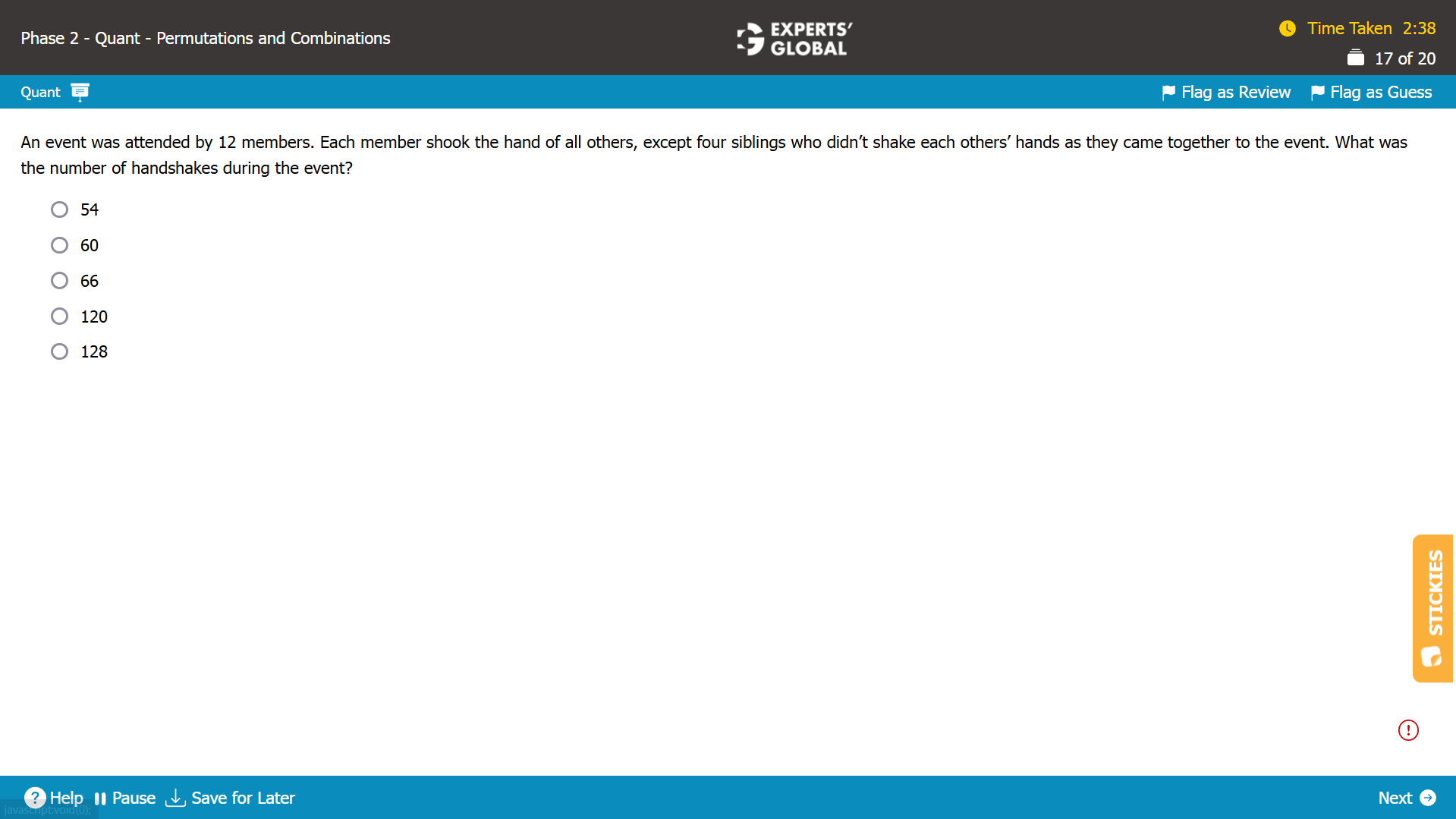

Between every pair of 2 individuals, there would be a handskake.

Number of pairs in 12 members = 12C2 = 66.

So, there would be 66 handshakes if every pair of 2 individuals had a handshake.

4 siblings did not shake hands with each other.

Number of pairs in 4 members = 4C2 = 6.

Number of handshakes in 4 members = 6.

The number of handshakes that did not take place need to be subtracted from the number of all handshakes.

So, number of handshakes during the event = 66 – 6 = 60.

60 handshakes took place during the event.

B is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

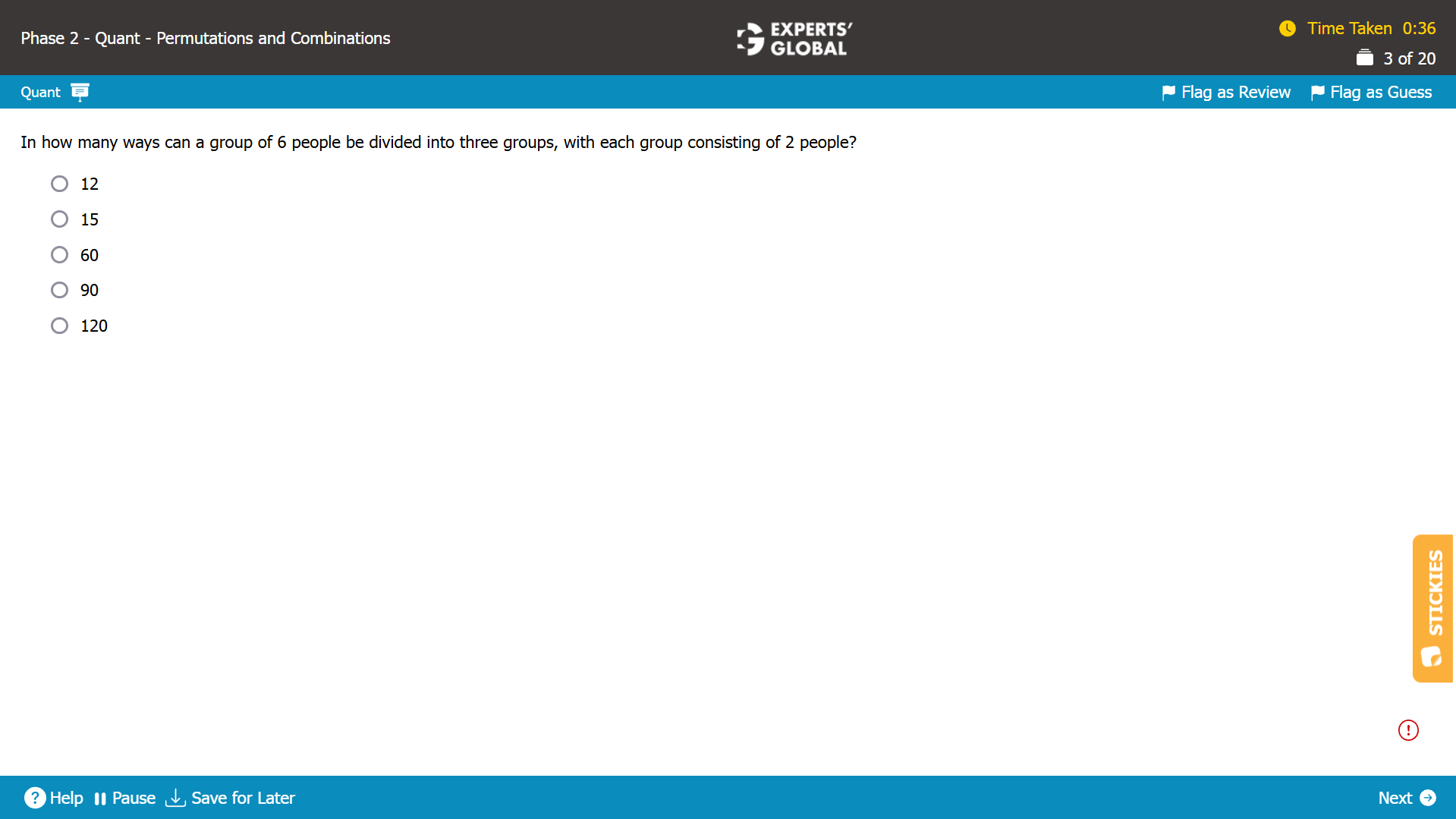

Let’s pick 2 people per group.

For the first group, there are 6 people available and 2 need to be picked.

The first group can be formed in 6C2 ways.

For the second group, there are 4 people available and 2 need to be picked.

The second group can be formed in 4C2 ways.

For the third group, there are 2 people available and 2 need to be picked.

The third group can be formed in 2C2 ways.

Total number of ways of forming the three groups 6C2 x 4C2 x 2C2 ways.

In these number of ways, there will be three ways of picking up such that ….

… in the first way of picking up, individual X and individual Y were picked up as part of the first group, whereas

… in the second way of picking up, individual X and individual Y were picked up as part of the second group, whereas

… in the third way of picking up, individual X and individual Y were picked up as part of the third group.

These three ways of picking the three groups should be counted as only one way.

Overall, the repetitions need to be accounted for by dividing the total number of ways by the number of ways in which the three groups could have been ordered.

The three groups can be ordered in 3! ways.

Total number of ways of forming the three groups, without repetition = (6C2 x 4C2 x 2C2) / (3!) ways = (15 X 6 X 1) / (6) = 15.

There are 15 ways in which the group of 6 can be divided into 3 groups of 2.

B is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

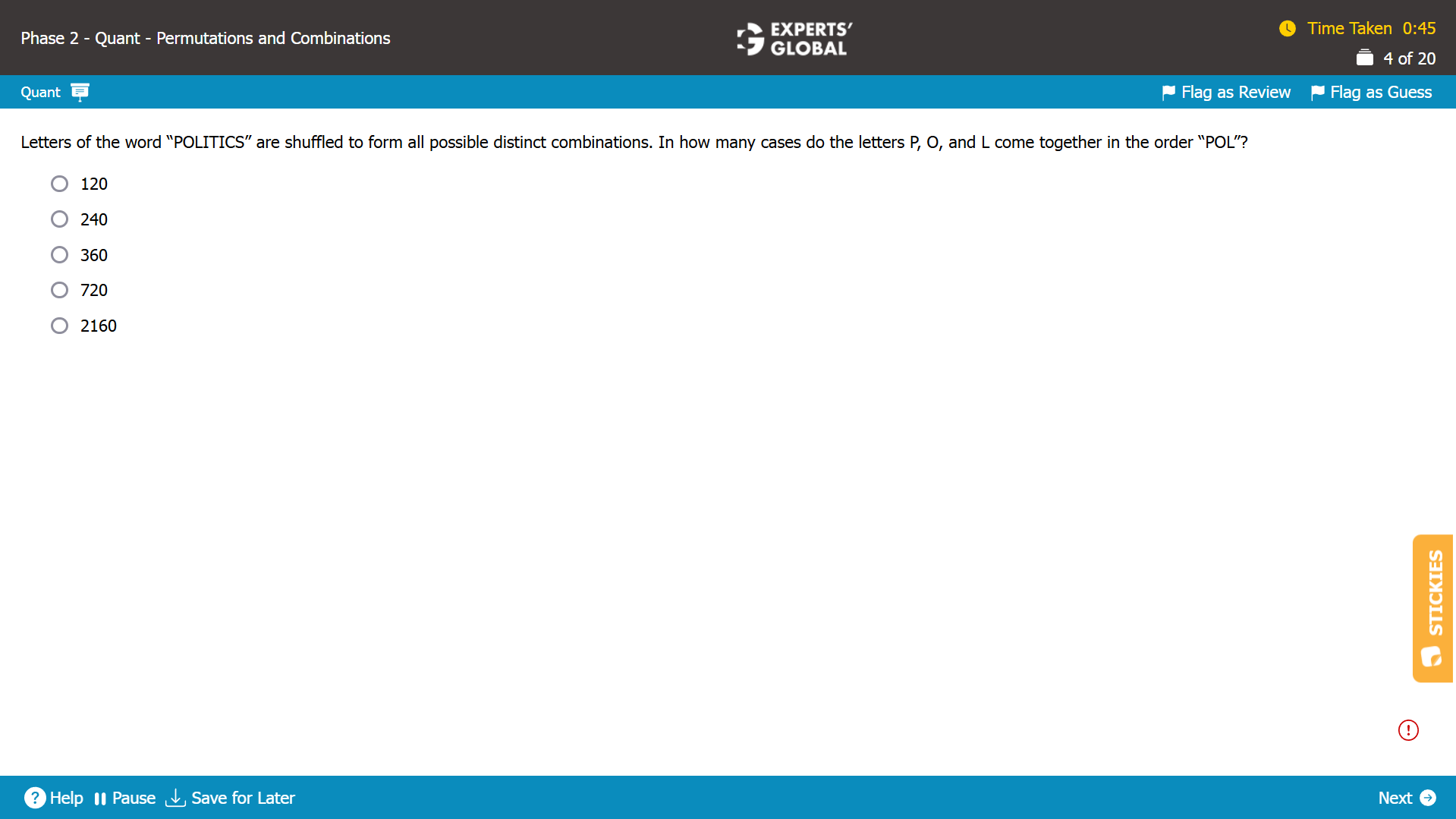

Total number of letters in the word “POLITICS” = 8.

If P, O, L come together in the same form “POL”, “POL” can be considered one unit.

Total number of units to be arranged = 8 – 3 + 1 = 6.

Number of ways in which 6 units can be arranged = 6!

These 6! ways treat two individual I’s differently; the order of the individual letters is not important; so, the two I’s must be treated as the same letter.

There are 2 I’s; so, there will be 2! ways of arranging the I’s.

Number of ways = 6! / (2!) = 360.

The required arrangement can be done in 360 ways.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

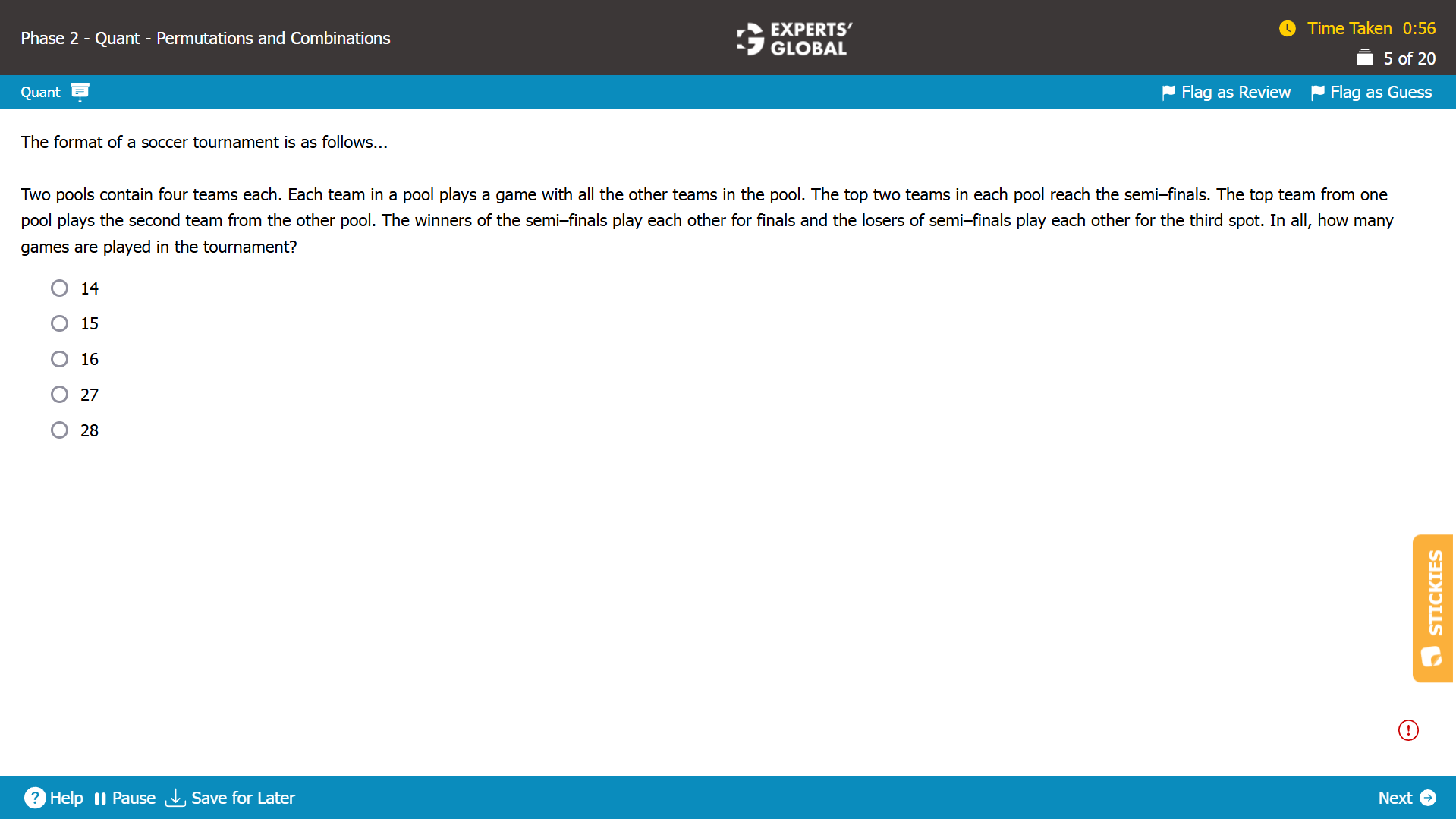

Let’s find the number of games played before the semi-finals.

In the first pool, there are 4 teams that play against one another.

Number of games in the first pool = 4C2 = 6.

In the second pool, there are 4 teams that play against one another.

Number of games in the second pool = 4C2 = 6.

In the semi-finals, there are two semi-finals.

Number of semi-finals played = 2.

After the semi-finals, there is one final.

Number of finals played = 1.

After the semi-finals, there is one game played for the third spot.

Number of games played for the third spot = 1.

Total number of games = 6 + 6 + 2 + 1 + 1 = 16.

16 games are played in the tournament.

C is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

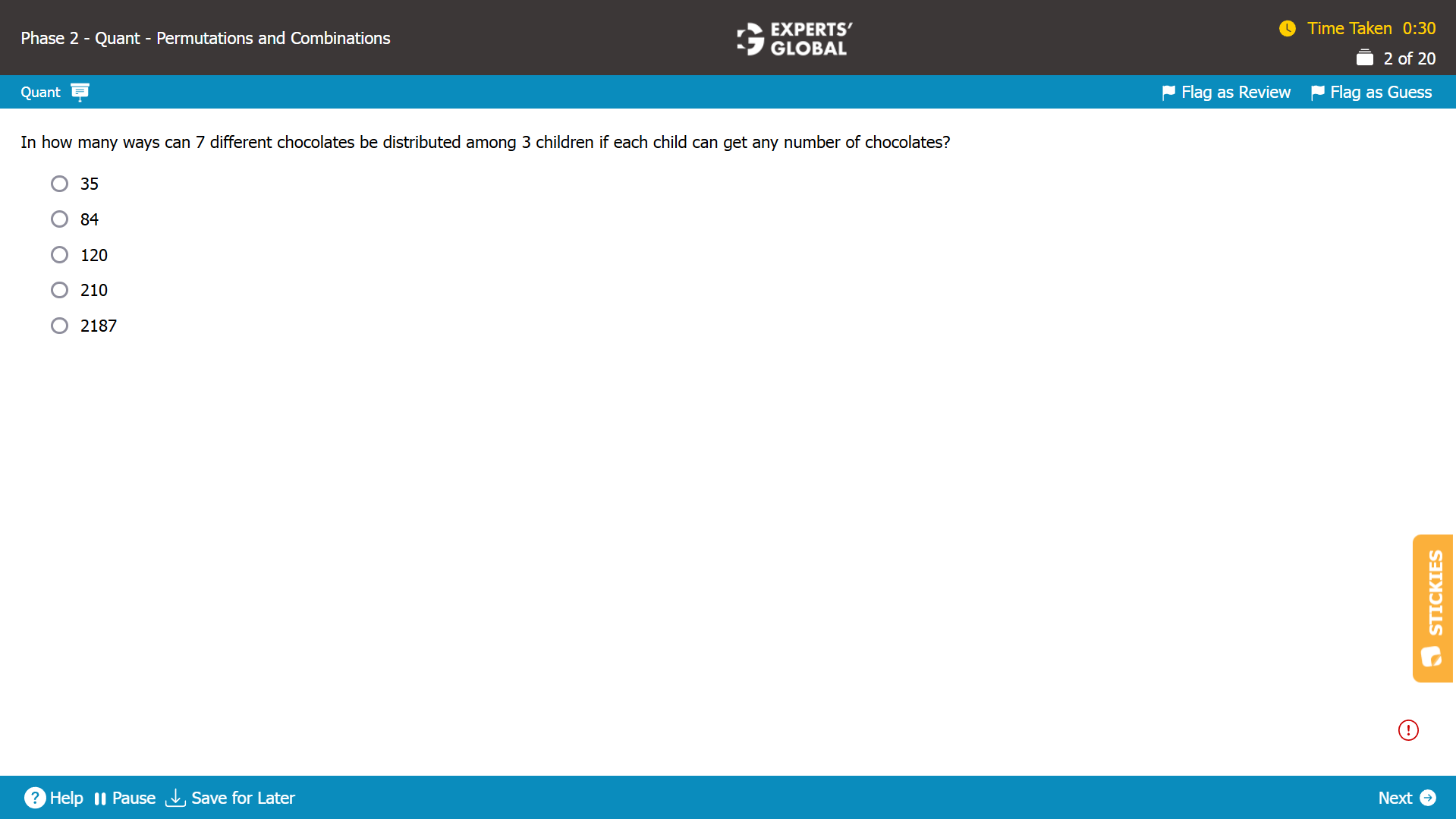

Each chocolate can go to any of the children. That is, all of 7 chocolates have 3 options to go to. So the required ways are 37 = 2187.

Hence, E is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

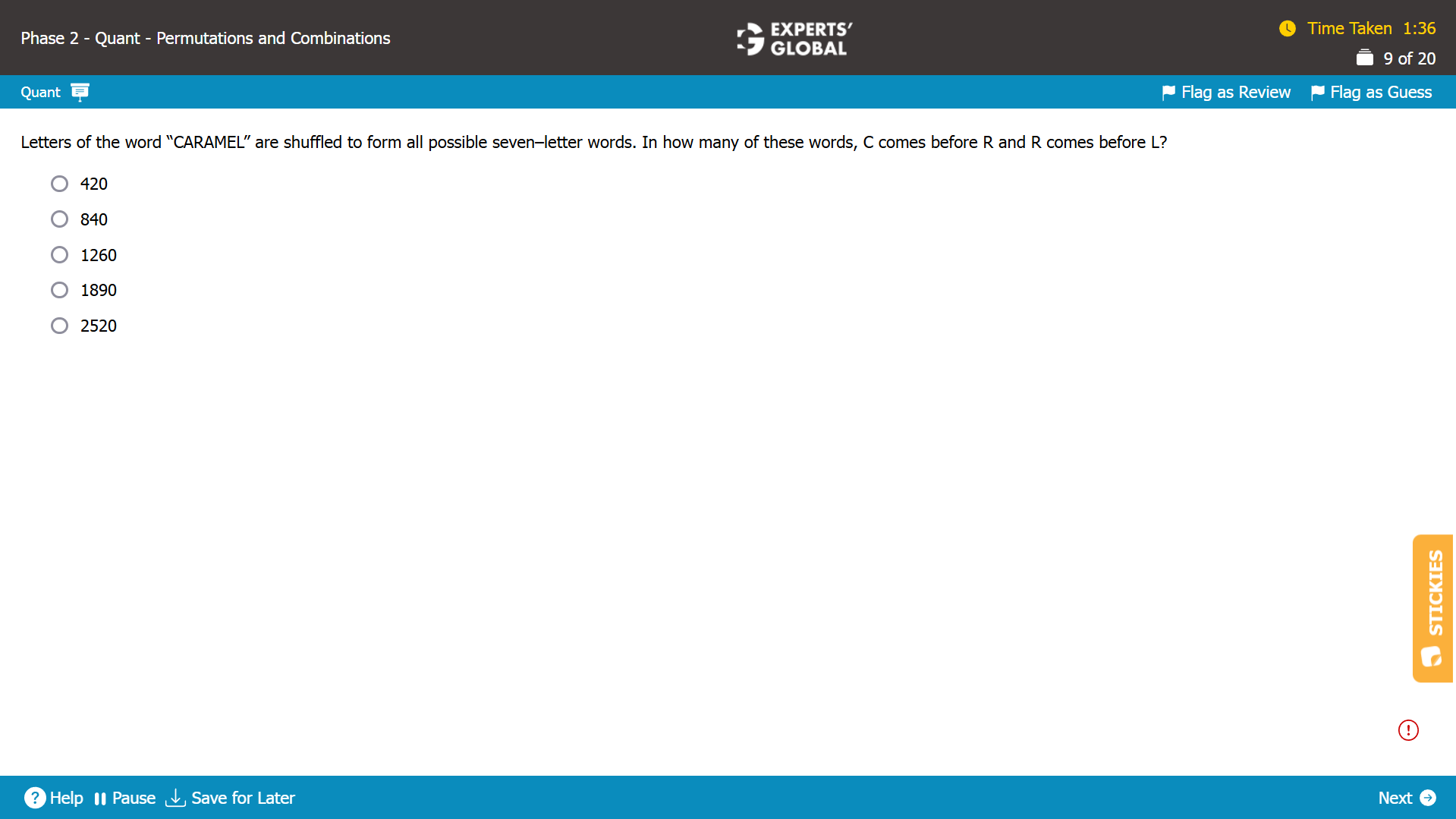

Total number of letters in the word “CARAMEL” = 7.

Number of ways in which 7 letters can be arranged = 7!

These 7! ways treat two individual A’s differently; the order of the individual letters is not important; so, the two A’s must be treated as the same letter.

There are 2 A’s; so, there will be 2! ways of arranging the A’s.

Number of ways = 7! / (2!) = 2520 …. (Statement I)

Let’s consider the arrangements of C, R, and L.

Number of letters = 3.

3 letters can be arranged in 3! = 6 ways.

Out of these 6 ways, only one arrangement is such that “C comes before R and R comes before L”. The same will hold true even if there are other letters apart from C, R, and L in the arrangement.

In other words, in the 2520 arrangement of CARAMEL, as per Statement I, only 1 arrangement among 6 arrangements will be such that “C comes before R and R comes before L”.

Overall, the number of requirement arrangements = 2520 / 6 = 420.

The required arrangement can be done in 420 ways.

A is the correct answer choice.

Show Explanation

Written Explanation

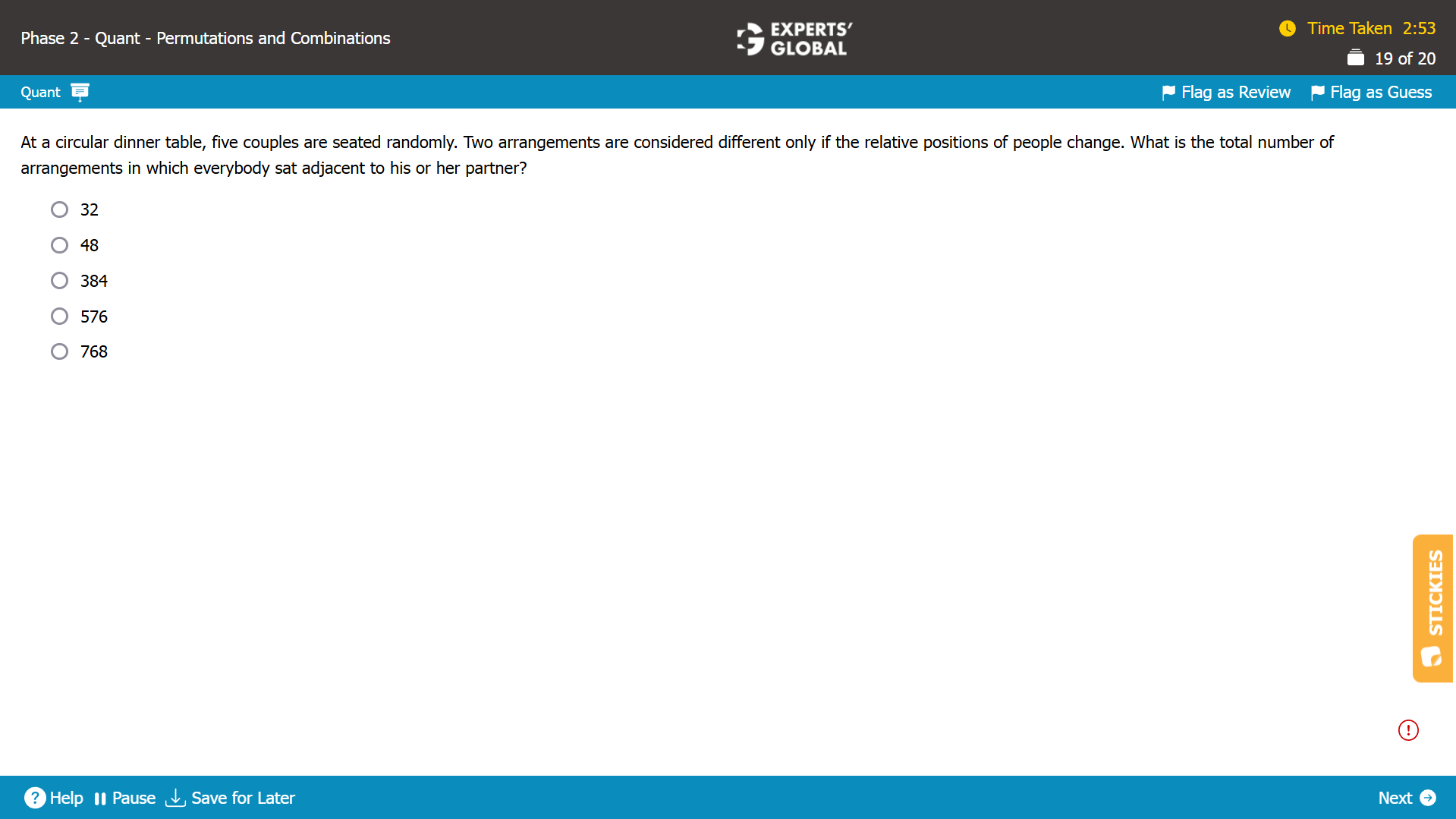

Let’s consider an arrangement in which everybody in the five couples is sitting adjacent to their partners.

Relative to the first couple in a circular table, number of ways in which five couples can sit = (5 – 1)! = 24 ways.

The two individuals in a couple can sit in 2 different orders: husband-wife or wife-husband.

Number of ways in which the two individuals in a couple can sit adjacent to each other = 2.

The same applies to all five couples.

So, total number of required arrangements = number of ways in which five couples can sit X (number of ways in which the two individuals in a couple can sit adjacent to each other)5

Total number of required arrangements = 24 X (2)5 = 24 X 32 = 768.

The required arrangement can be done in 768 ways.

E is the correct answer choice.

High quality Permutations and Combinations questions are not available in large numbers. Among the limited, genuinely strong sources are the official practice materials released by GMAC and the Experts’ Global GMAT course. Within the Experts’ Global GMAT online preparation course, every Permutations and Combinations problem appears on an exact GMAT like user interface that includes all the real exam tools and features. You work through more than 70 Permutations and Combinations questions in quizzes and also take 15 full-length GMAT mock tests that include several Permutations and Combinations questions in roughly the same spread and proportion in which they appear on the actual GMAT.

All the best!