Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

When you see numbers on GMAT CR, look at them closely, as they generally hide both trap and key. Focus on context and scale. Example: a 99% success rate may sound impressive yet is unacceptable for surgeries or aeroplane landings, where a 1% failure is outrageous.

Numbers in Critical Reasoning may appear authoritative, yet their value depends on context, comparison, and the link to the conclusion. This overview outlines how to read figures with discipline: ask “compared to what,” check scope, relate metrics to the claim, and watch for benchmarks and alternative causes. Video and article illustrate how numbers can strengthen, weaken, explain, or evaluate an argument. The same habits support evidence-based thinking across GMAT prep and MBA admissions, where quantitative claims must be interpreted.

One of the subtle yet powerful traps in GMAT Critical Reasoning lies in numbers. They appear convincing because they carry the weight of an impression, but they can often be misleading. Whenever you see numbers in an argument, slow down, examine them carefully, and ask yourself if they are being used fairly.

Arguments may present figures such as “the highest in 50 years” or “a 50% growth.” These are impressive at face value. However, without context, they can lead to a false impression. Numbers need comparison, perspective, and proper linkage to the conclusion. If these are missing, the argument is vulnerable.

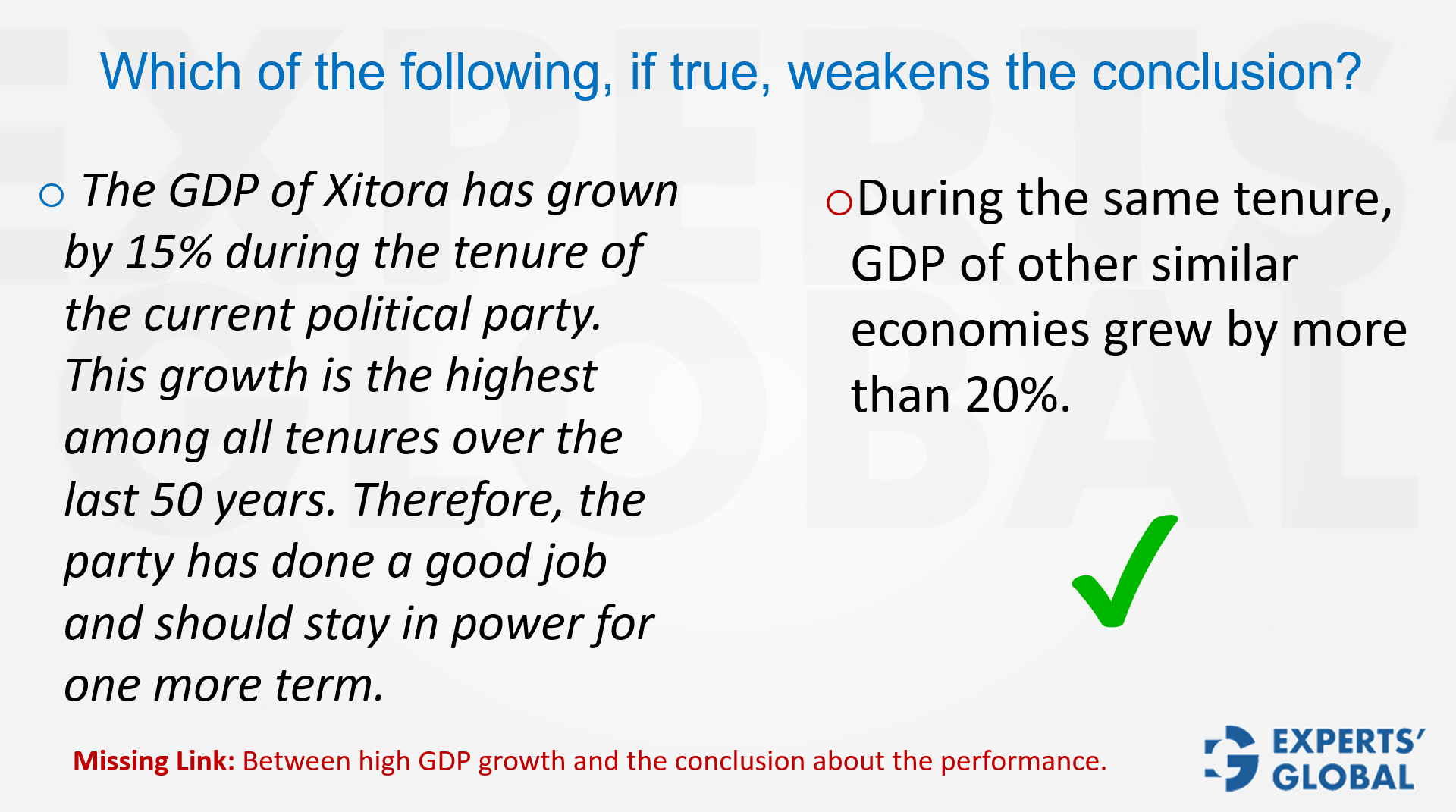

Consider this argument:

“The GDP of Xitora has grown by 15% during the tenure of the current political party. This growth is the highest in the past 50 years. Therefore, the party has done a good job and should remain in power.”

The gap here is between the GDP growth and the conclusion about the party’s performance. At first glance, 15% growth sounds very strong, and the phrase “highest in 50 years” reinforces this impression.

However, when we introduce the statement:

“Other similar economies grew by more than 20% during the same period,”

the entire conclusion is weakened. The word “similar economies” makes the analogy relevant, and now, the once-impressive 15% is no longer good enough.

The catch in this question lies squarely in the numbers. This simple example teaches the importance of examining the numbers carefully in GMAT’s CR questions.

Numbers in Critical Reasoning questions carry weight but can mislead if taken without context. Always ask what the figure is compared against, whether it links premise to conclusion, and if it alters the argument’s strength. Phrases like “highest in 50 years” may impress yet lack relevance. Correct use involves comparisons, benchmarks, or related factors. Practicing this approach in GMAT simulations builds the habit of evaluating numerical evidence critically, ensuring accuracy and sharper reasoning under exam conditions.

Numbers remind us that data alone does not carry meaning; it is the interpretation that creates insight. In GMAT preparation, learning to question figures cultivates discipline in separating surface impressions from deeper truths. In MBA applications, the same principle applies—statistics about achievements or results only matter when framed with context and relevance. In life, too, progress requires us to look beyond attractive figures and examine what they truly represent. Each GMAT mock offers practice in this discernment, strengthening the ability to interpret numbers with clarity and balance.