Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Confusing cause with effect means assuming A causes B when, in fact, B causes A. Example: Cities with more bike lanes have more cyclists. Inferring that many cyclists lead to bike lanes reverses the link. Actually, building bike lanes leads to more cycling.

This overview introduces a core logic theme on GMAT Critical Reasoning: distinguishing cause from effect. You will learn to check directionality, consider third factors, and use quick diagnostics: timelines, controlled comparisons, and counterexamples to evaluate causal claims across various CR question types. The video sets the framework; the article provides a concise checklist for disciplined, sharp analysis. These habits elevate evidence-based reasoning in GMAT prep and transfer to data-informed judgments valued throughout MBA admissions and decision-making in study and practice.

One of the frequently tested logical flaws on the GMAT is confusing cause with effect. This happens when the supposed cause is actually the effect, or when the supposed effect is actually the cause. The test makers use this trap because many real-life arguments casually mix up causes and effects, and the GMAT expects you to recognize the error.

Take the statement:

Every time I dream, I sleep.

At first, this may appear correct, but the reasoning is flawed.

The argument suggests that dreaming causes sleep, when in fact sleep is the cause, and dreaming is the effect.

Similarly,

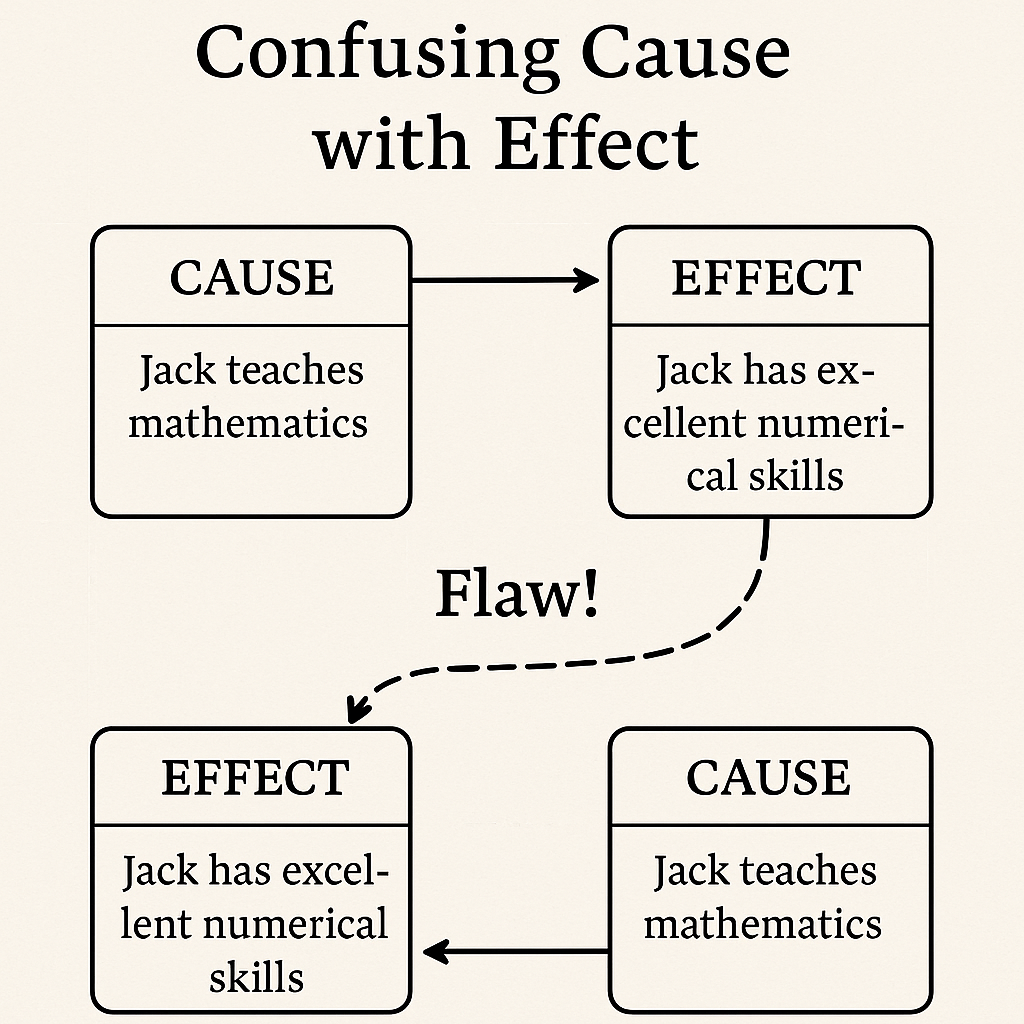

Jack teaches mathematics. Jack has excellent numerical skills. Thus, teaching mathematics improves one’s numerical skills.

This may seem correct on first look but a closer look would suggest that this argument suffers from the fallacy of confusing cause with effect.

This reasoning suggests “teaching mathematics” is the cause and “excellent numerical skills” is the effect; however, a person lacking in numerical skills is unlikely to teach mathematics on the first place.

Hence, practically, “excellent numerical skills” is the cause and “teaching mathematics” is the effect.

Consider:

For the last 5 years, Hannah has suffered from back pain. During the same period, Hannah never engaged in any physically demanding activity. Therefore, not performing physically demanding activities can lead to back pain.

The reasoning here suggests that avoiding activity caused the pain.

However, it is equally possible, and more logical, that back pain is the cause of her reduced activity.

Identifying this flaw is crucial because the argument collapses once the direction of causality is corrected.

Consider:

A study comparing a group of people displaying anger disorder with an otherwise matched group of people free from anger issues found significantly more neurological disorders among the group exhibiting behavioral disorder comprising explosive outbursts of anger. According to researchers, these results support the hypothesis that anger influences human body’s neurological condition.

The conclusion assumes that anger is the cause and the disorder is the effect.

However, the flaw lies in not recognizing that neurological disorders could instead be causing the anger.

A correct answer choice on the GMAT would reverse this relationship, pointing out that the supposed effect may actually be the cause.

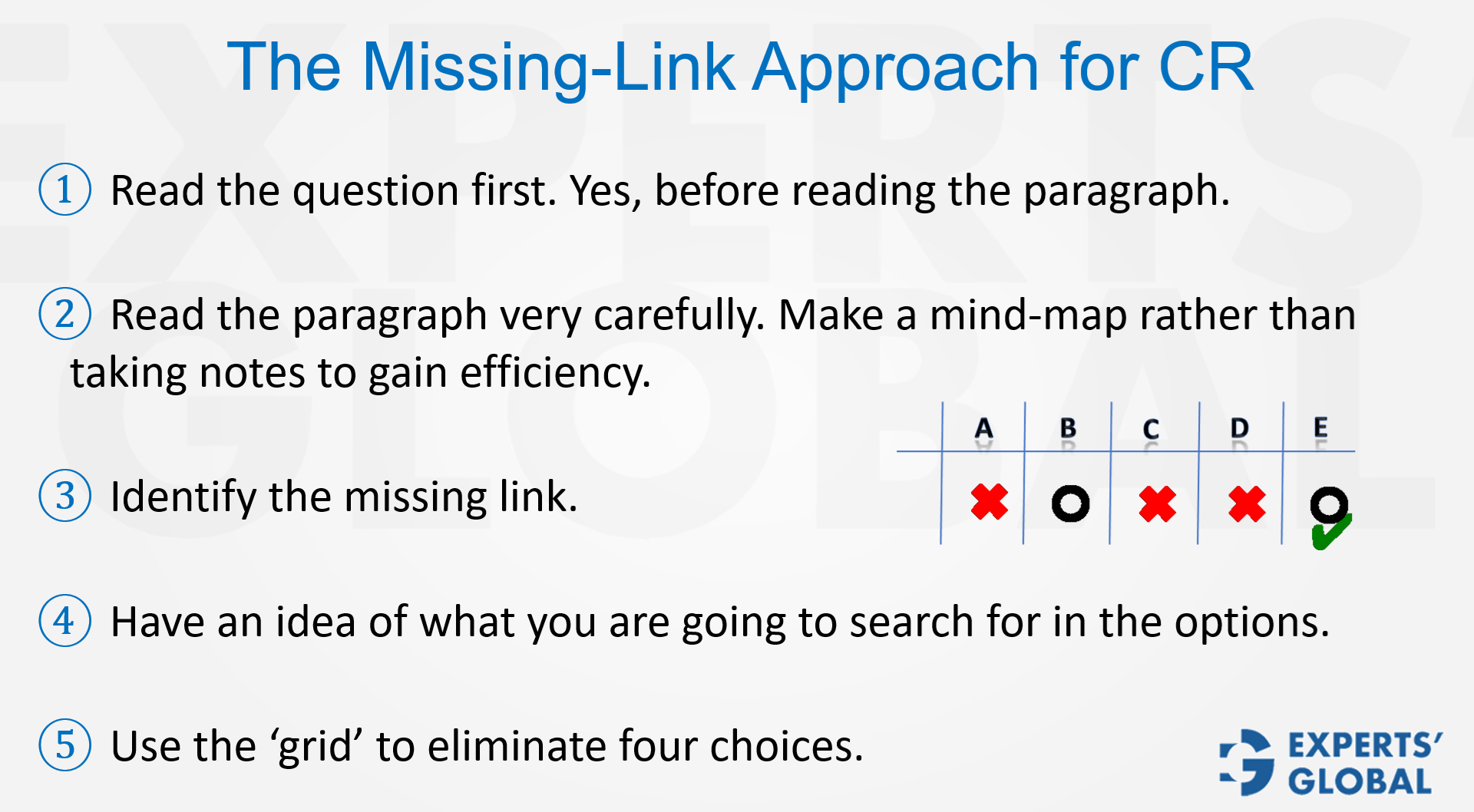

Step 1: Read the question stem, so the exact requirement is clear to you.

Step 2: Read the reasoning carefully; develop mind-map and identify the missing-link.

Step 3: Set your broad expectation from the correct answer choice.

Step 4: Eliminate four choices; one that’s left is your answer.

Before confirming the answer, verify.

Recognizing cause-effect flaws is not just about solving a particular question type; it is about seeing through faulty logic in any reasoning scenario. Many weakening questions on the GMAT rely on this very principle. By carefully questioning the direction of causality, you will avoid the trap that ensnares so many test takers.

This article emphasize the importance of questioning the direction of causality in GMAT Critical Reasoning. Arguments often reverse cause and effect, and success depends on identifying when the supposed cause is actually the result. Common patterns include health, behavior, or performance-based scenarios where reasoning is flipped. With consistent practice, you will learn to spot these traps quickly and avoid errors. Working through GMAT simulations ensures that you refine this analytical skill under authentic test conditions.

In life, as in reasoning, clarity often comes from asking whether what we see as cause is actually the effect. This insight is central to Critical Reasoning on the GMAT, where assumptions are tested and perspectives reversed. The discipline of pausing, questioning direction, and seeking deeper connections extends beyond test preparation. It shapes reflective thinking for GMAT mock practice, nurtures analytical precision in MBA applications, and builds resilience in professional and personal decisions. Recognizing the true flow of causality is not only a test skill but a lifelong guide to balanced judgment.