Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

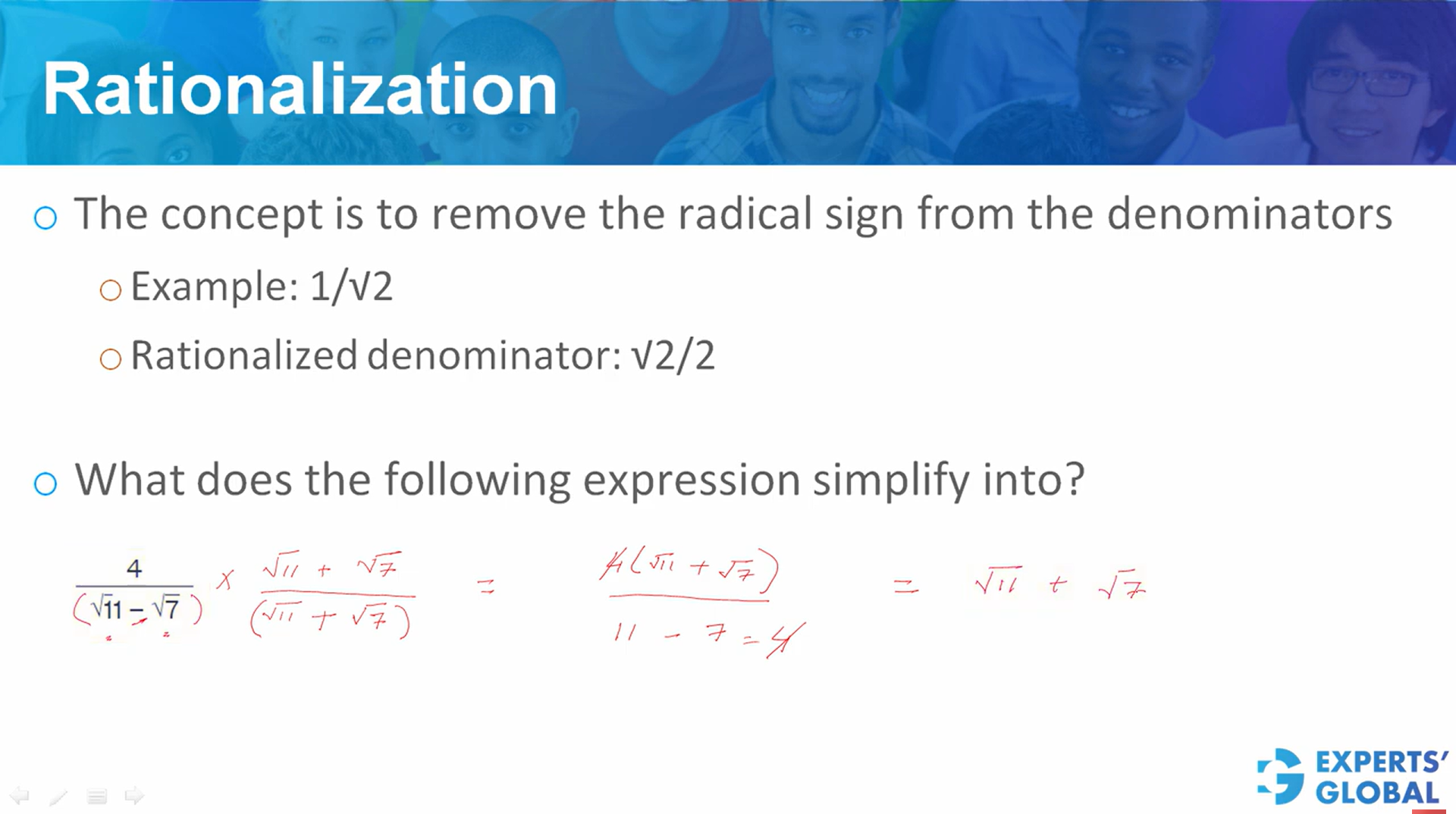

On the GMAT, rationalization means simply removing square roots from denominators. You multiply top and bottom by a conjugate [which changes (a + √b) to (a – √b)]. For instance, 1 ÷ (2 + √3) becomes 2 – √3 after rationalization.

Rationalization on the GMAT focuses on turning expressions with square roots in the denominator into cleaner, integer based forms by multiplying with suitable conjugates. This overview introduces how such simplification reveals structure, supports orderly manipulation of radicals, and prevents common misunderstandings about square roots. Practised consistently within your broader GMAT prep, these habits strengthen algebraic clarity and calm reasoning that later carry into data interpretation, quantitative arguments, and analytical work valued throughout MBA admissions and subsequent academic and professional settings.

Rationalization is the process of removing square roots from the denominator of a fraction by multiplying with a suitable expression, usually the conjugate. It is a simple idea, but it shows up often enough on the GMAT that it deserves a calm, thoughtful look. Once you understand how it works, many expressions that seem long or delicate suddenly feel straightforward.

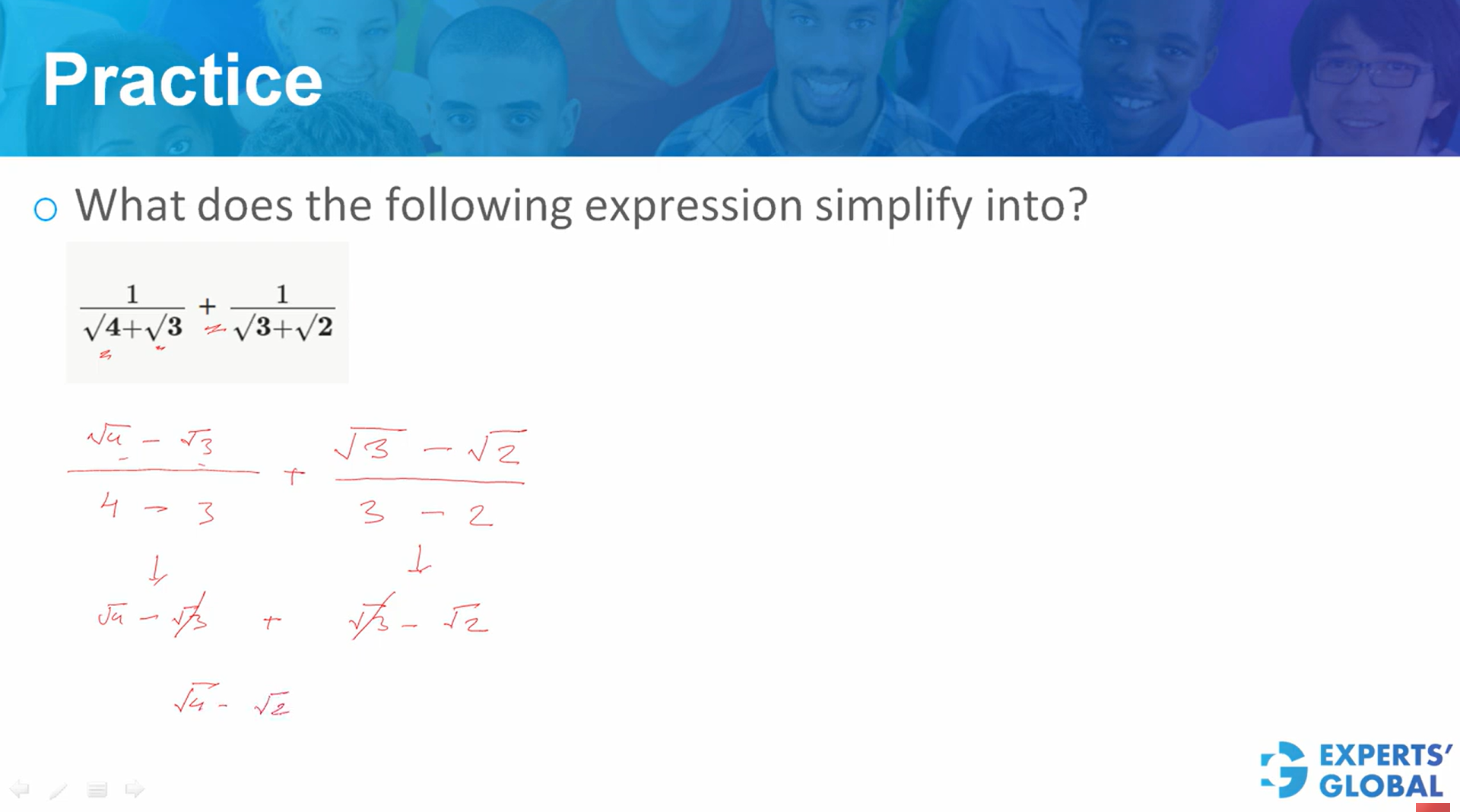

Consider the following expression:

1 / (√4 + √3) + 1 / (√3 + √2).

The question asks you to simplify this expression to its most compact form.

Start with the first fraction:

1 / (√4 + √3).

To rationalize the denominator, multiply the numerator and denominator by the conjugate (√4 − √3):

1 / (√4 + √3) × (√4 − √3) / (√4 − √3)

= (√4 − √3) / ((√4)² − (√3)²).

Compute the denominator:

(√4)² = 4, and (√3)² = 3.

So the denominator becomes 4 − 3 = 1. This leaves:

1 / (√4 + √3)

= √4 − √3.

Now rationalize the second fraction:

1 / (√3 + √2).

Multiply the numerator and denominator by (√3 − √2):

1 / (√3 + √2) × (√3 − √2) / (√3 − √2)

= (√3 − √2) / ((√3)² − (√2)²).

Again, compute the denominator:

(√3)² = 3, and (√2)² = 2.

So the denominator becomes 3 − 2 = 1, leaving:

1 / (√3 + √2) = √3 − √2.

Now add the two simplified terms:

(√4 − √3) + (√3 − √2)

= √4 − √2.

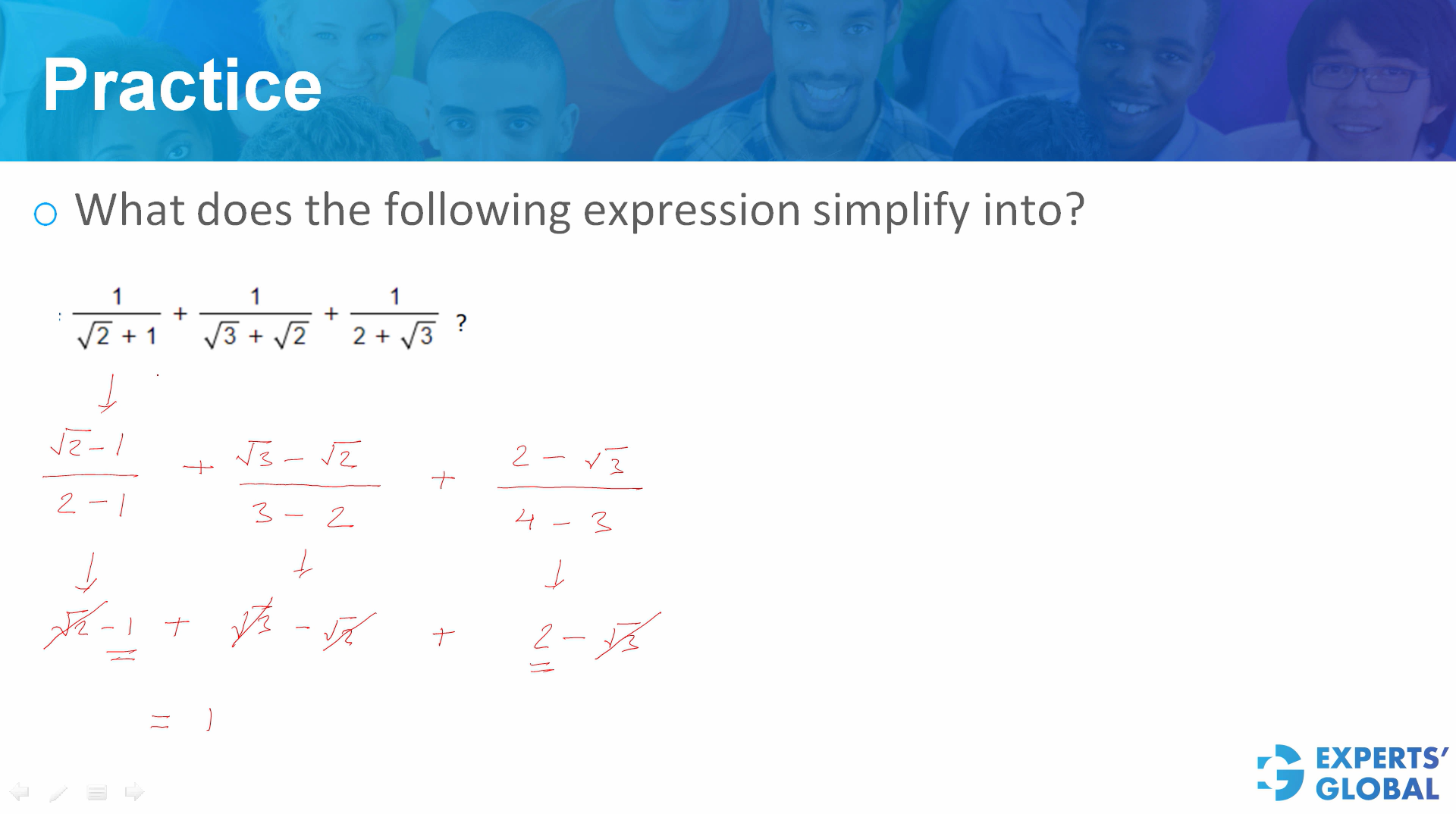

Now consider a more elaborate expression:

1 / (√2 + 1) + 1 / (√3 + √2) + 1 / (2 + √3)

Again, the goal is to simplify this entire expression.

Start with the first term:

1 / (√2 + 1).

Multiply numerator and denominator by the conjugate (√2 − 1):

1 / (√2 + 1) × (√2 − 1) / (√2 − 1)

= (√2 − 1) / ((√2)² − 1²)

= (√2 − 1) / (2 − 1)

= √2 − 1.

The first term simplifies to √2 − 1.

Now take the second term:

1 / (√3 + √2).

As before, multiply by the conjugate (√3 − √2):

1 / (√3 + √2) × (√3 − √2) / (√3 − √2)

= (√3 − √2) / ((√3)² − (√2)²)

= (√3 − √2) / (3 − 2)

= √3 − √2.

The second term simplifies to √3 − √2.

Finally, consider the third term:

1 / (2 + √3).

Multiply by the conjugate (2 − √3):

1 / (2 + √3) × (2 − √3) / (2 − √3)

= (2 − √3) / (2² − (√3)²)

= (2 − √3) / (4 − 3)

= 2 − √3.

Now add the three simplified terms:

(√2 − 1) + (√3 − √2) + (2 − √3).

Group like terms:

√2 and −√2 cancel each other.

√3 and −√3 cancel each other.

The remaining constants are −1 + 2 = 1.

So, the entire expression simplifies beautifully to 1.

A long and apparently complex expression collapses into a single, simple number. This is a typical GMAT experience. The test often hides a very neat result inside a busy looking expression, and rationalization is one of the keys that unlocks it.

One frequent mistake is to treat √100 as both 10 and −10. This comes from confusing two different ideas. The equation x² = 100 has two solutions, x = 10 and x = −10. But the expression √100 refers to the principal square root only, which is 10. Remember that √k has a single non negative value. Keeping this distinction clear prevents you from doubling your answers by accident.

Another common slip is to forget that you must multiply both numerator and denominator by the conjugate. If you only adjust the denominator, you change the value of the fraction. Multiplying top and bottom together keeps the expression equivalent while changing its appearance.

Rationalization is more than a mechanical tool. It teaches you to trust that order may be hiding inside what looks complicated. Each time you multiply by a conjugate and watch terms cancel, you strengthen your faith in structure and patterns. That faith is important when the exam clock is ticking and your mind is tempted to panic.

As you keep meeting such expressions in each GMAT drill, you are not only getting faster with radicals. You are also practising a way of thinking that looks for symmetry, respects basic identities, and believes that calm, stepwise work can bring clarity. That same habit will serve you in data analysis, finance, operations, and in the many case discussions and projects of your MBA and professional life.

Rationalization on the GMAT teaches you to replace square roots in denominators with clean integers using conjugates, so long expressions collapse into neat, interpretable results. Through two practice examples, you see how radicals simplify, how common errors with principal square roots are avoided, and how careful algebra builds steady confidence with fractions and radicals. Repeated work in GMAT simulations turns this technique into a natural part of your problem solving rhythm, supporting clear thinking in broader quantitative study and analysis.

Rationalization quietly reminds you that many tangled expressions, in mathematics and in life, can be cleared by one thoughtful step at a time. When you multiply by a conjugate, you are choosing structure over noise, patience over hurry. The same habit supports you when a case study feels dense, when data in an internship project looks scattered, or when application choices compete for your attention. Each carefully solved example and each GMAT mock becomes a small rehearsal in believing that calm, honest work can reveal patterns that were always present, waiting to be seen. That trust enriches study, work, relationships.