Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

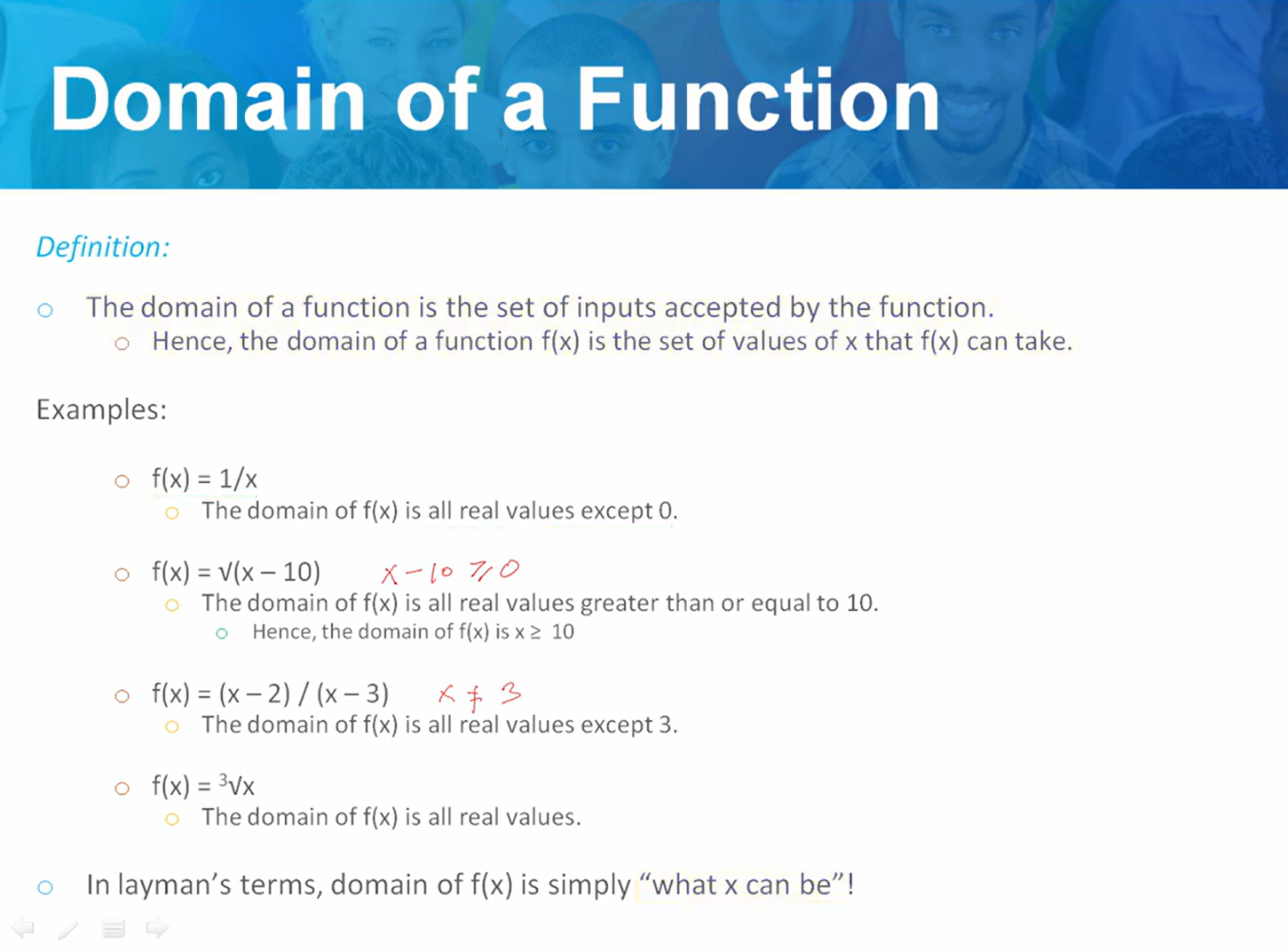

The domain of a function is the complete set of input values for which the function is defined. For example, if f(x) = x2, you can square any real number, so the domain is all real numbers. If g(x) = 1 ÷ x, you cannot divide by zero, so every real number except x = 0 belongs to the domain.

The domain is simply the list of all allowed inputs that keep the function meaningful. This lesson introduces the idea of domain as the set of real x values for which a function is defined and meaningful. You learn how simple structural features, such as denominators and radical signs, quietly decide which inputs are allowed and which are excluded. A calm, careful view of domain consistently strengthens your overall GMAT prep and deepens the logical habits that later support thoughtful MBA admissions decisions, where clear reasoning about conditions, constraints, and implications matters just as much.

A function f(x) opens its world to you only when you know what x is allowed to be. The domain is that world. It is the complete set of x values for which the function is defined. When students first hear this definition, it sometimes sounds technical, but the heart of the idea is very human. Every function has boundaries, and those boundaries arise from simple mathematical behavior. When you see the domain clearly, you begin to see the structure beneath every expression. This lesson walks you through each idea patiently, using examples that echo the quiet logic of the GMAT.

Domain is the set of inputs the function accepts. If a function cannot compute a value for a particular x, that x does not belong to its domain. This may happen because a denominator becomes zero, a square root becomes negative, or an expression demands a value that mathematics does not allow. When you understand why a value is excluded, the idea no longer feels mechanical. It becomes intuitive, almost natural.

Here, x can take any real number except 0.

When x = 0, the denominator becomes zero, which is not permissible.

So the domain is all real values of x except 0.

This is the simplest example of how a denominator shapes the domain. One forbidden point creates a quiet gap on the number line, and that gap carries meaning.

A square root demands that the expression inside it remain non negative.

For √(x − 10), we require x − 10 ≥ 0. This gives x ≥ 10.

The domain is every real value greater than or equal to 10.

Once again, the function reveals its boundaries through its structure. It asks for values that keep its radical steady and real.

Here, x = 3 makes the denominator zero.

Therefore, the domain is all real values except 3.

A single point is excluded because the function collapses at that point.

Odd roots behave with remarkable freedom.

∛(x − 8) allows every real value of x.

Negative numbers, zero, and positive numbers all pass through an odd root without strain.

The domain here is all real numbers.

If the definition ever feels heavy, remember a lighter version. Domain simply answers the question: What can x be?

For f(x) = 1/x, x can be anything except 0.

For √(x − 10), x can be anything that keeps the inside non negative.

For odd roots, x can be anything at all.

Domain is nothing more than the set of acceptable x values.

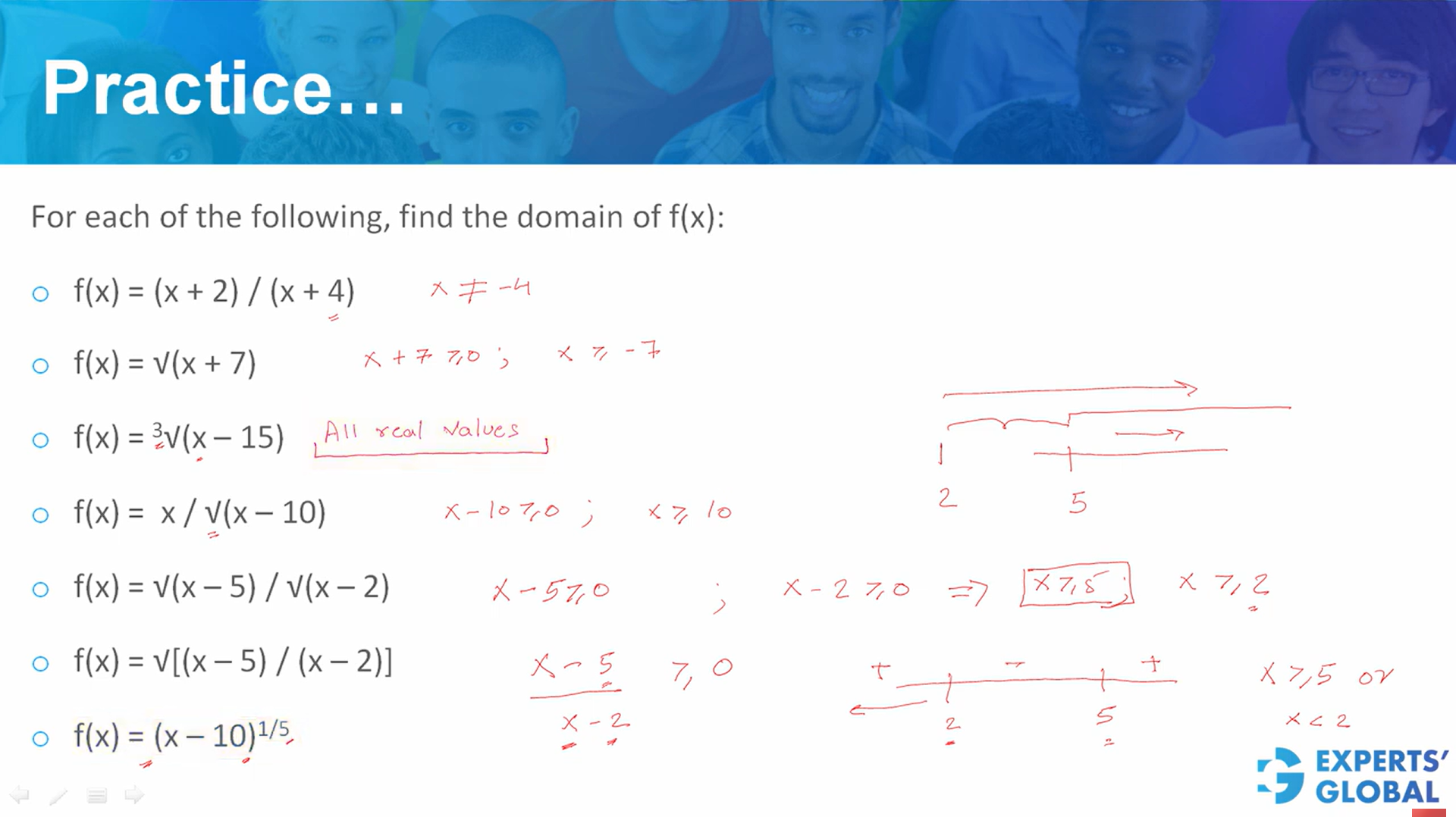

Below is a sequence of examples that mirrors the quiet reasoning of the GMAT. Each is solved completely so you can see the domain unfold with patience and clarity.

The denominator becomes zero when x = −4.

This single value must be excluded.

So the domain is all real values of x except x = −4.

Inside the square root, x + 7 must be ≥ 0.

This gives x ≥ −7.

The domain is all real values greater than or equal to −7.

This is an odd root.

Negative, zero, and positive values are all acceptable.

So the domain is all real numbers.

Just as before, x − 10 ≥ 0.

Thus x ≥ 10.

The domain is all real values greater than or equal to 10.

Two conditions appear.

First, √(x − 5) requires x ≥ 5.

Second, the denominator (x − 2) cannot be zero, so x ≠ 2.

Now, compare the two.

The condition x ≥ 5 is stronger because every value ≥ 5 is already greater than 2.

So, the only effective restriction is x ≥ 5.

The domain is all real values greater than or equal to 5.

Here, the entire fraction sits inside the square root, so the expression (x − 5)/(x − 2) must be ≥ 0.

To understand where this happens, mark two critical points on the number line: 2 and 5.

For values greater than 5, both numerator and denominator are positive, so the expression is positive.

Between 2 and 5, the numerator is negative while the denominator is positive, so the expression becomes negative.

For values less than 2, both numerator and denominator are negative, and the expression becomes positive again.

We now gather the valid regions: x > 5 or x < 2. However, x cannot be equal to 2 because the denominator becomes zero. At x = 5, the expression becomes zero, which is acceptable for a square root. So the domain is x ≥ 5 or x < 2.

This question often feels challenging because both numerator and denominator participate in shaping the domain. When students solve it correctly, they realise how far their understanding has grown.

Once again, this is an odd root.

Every real value is acceptable, so the domain is all real numbers.

This lesson clarifies domain as the set of x values for which a function is defined and meaningful. You see how denominators, square roots, and odd roots restrict or allow inputs, and how inequalities arise naturally from these structures. Working through examples inside high quality GMAT simulations reinforces these ideas, so domain checks become a steady habit that supports accurate reasoning across functions, word problems, and data driven questions. This quiet discipline strengthens confidence and fosters mature mathematical judgment overall.

When you pause to think about domain, you are really practicing a deeper habit of asking what is allowed, what is not, and why. This small question shapes every function you study, every GMAT mock you review, and every business situation you later analyze. In MBA essays, interviews, and careers, wise decisions often begin with noticing hidden conditions and silent boundaries. If you train yourself to see those limits gently and early in mathematics, you teach your mind to listen carefully before acting anywhere. That quiet awareness becomes a lifelong strength, guiding your choices, relationships, and leadership with thoughtful clarity.