Invest 30 seconds...

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

Help Line

- +91.8800.2828.00 (IND)

- 1030-1830 Hrs IST, Mon-Sat

- support@expertsglobal.com

...for what may lead to a life altering association!

The assuming similar bases fallacy draws conclusions from comparisons while presuming the starting bases were equal. Example: Price of A rises 50%, price of B rises 40%; claiming A is costlier now ignores bases; if A was originally $50 and B $100, B costs more.

Comparative arguments often rely on hidden starting-point assumptions. This overview introduces the baseline-equivalence check: before attributing outcomes to a program or event, confirm groups were comparable on relevant preconditions. Look for prior tendencies, selection effects, pre-test measures, and confounders, then judge claims accordingly. The video frames core diagnostics; the article offers practical examples and prompts. Mastering this lens supports rigorous reasoning in GMAT prep and evidence appraisal in MBA admissions, where disciplined comparisons strengthen analysis without overreach or unstated premises.

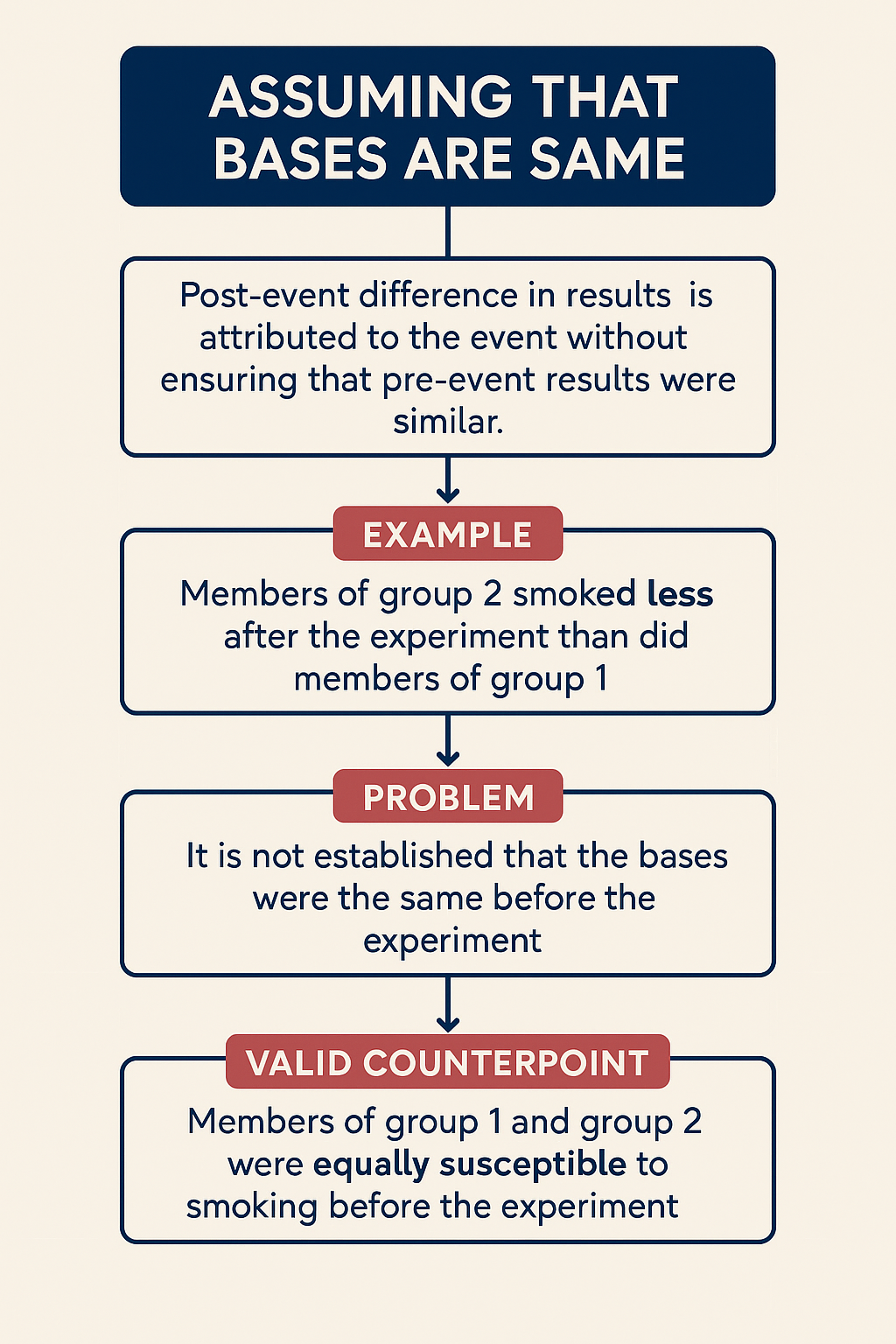

One of the common reasoning flaws tested in GMAT Critical Reasoning is the error of assuming that the initial bases of two entities, being compared post an event, are same. This fallacy occurs when post-event differences are attributed directly to the event itself, without confirming that the pre-event conditions were identical. In other words, the reasoning ignores the possibility that the groups being compared were unequal from the very beginning.

Consider the following argument…

After participating in a new training program, Group A scored significantly higher on an intelligence test compared to Group B, which did not attend the program. Therefore, the training program caused the improvement.

At first glance, this reasoning may appear convincing. However, the critical flaw lies in not establishing whether Group A and Group B had similar IQ levels before the program began. If Group A already had higher IQ scores prior to the experiment, the conclusion becomes invalid.

Consider the following argument…

Group 1 was shown a movie with 30 scenes in which an actor smoked a cigarette. Group 2 was shown a movie with no such scenes. Within one hour of seeing their respective movies, 40% of Group 1 members took a smoke, whereas only 20% of Group 2 members did so. The experiment establishes that seeing actors in a movie smoke instigates one’s instinct to do so.

Question: Which of the following pieces of information would be most necessary for evaluating the validity of the described experiment’s conclusion?

Correct Answer: Whether the members of group 1 and group 2 were equally susceptible to smoking before the experiment.

This information is essential because if one group was already less inclined to smoke before the workshop, the conclusion that the workshop itself caused the reduction would not be justified.

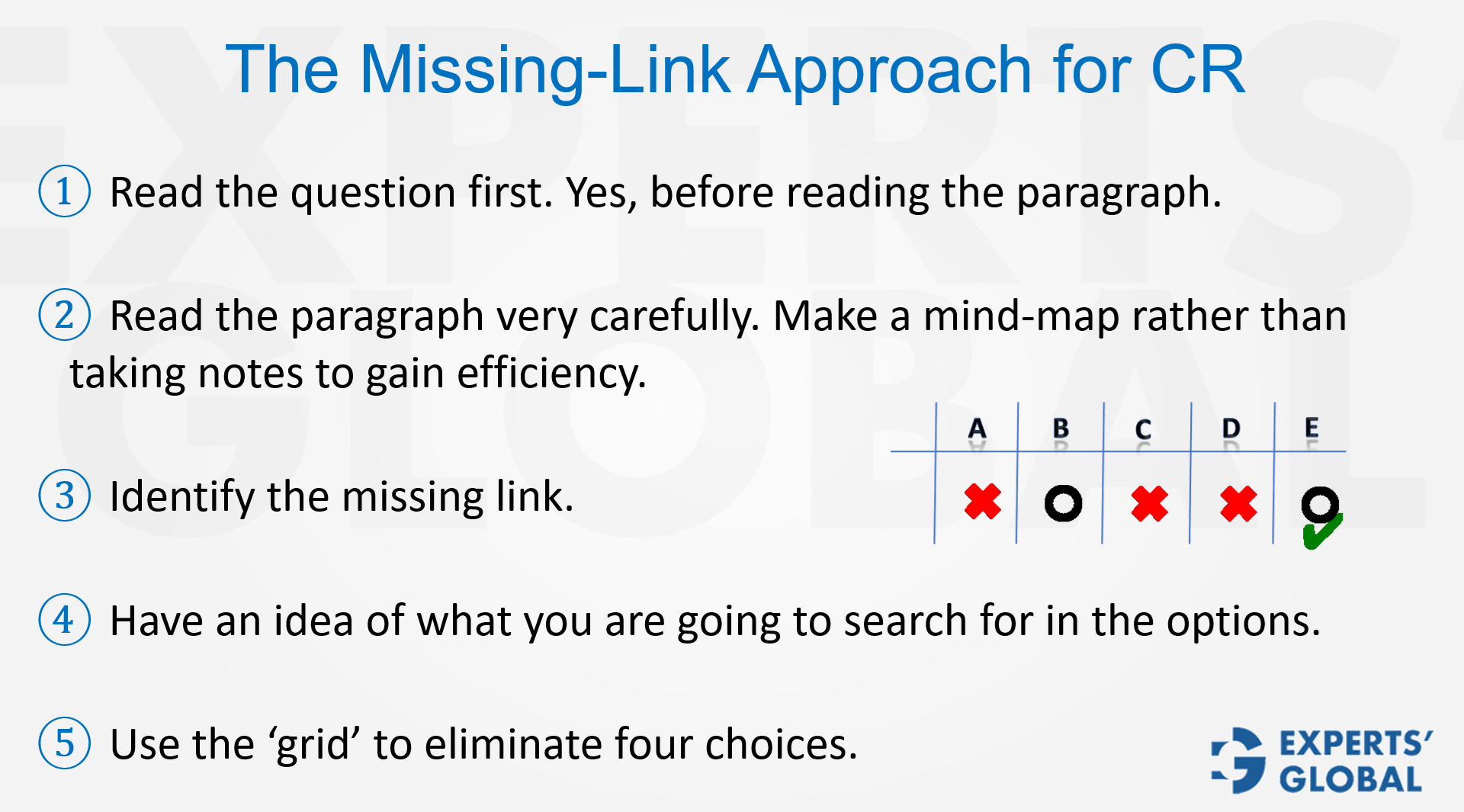

Step 1: Start with the question stem to fix the precise requirement in mind.

Step 2: Read the reasoning closely; create a Mind map and identify the missing link.

Step 3: Formulate your broad expectation from the correct answer choice.

Step 4: Eliminate four options; the option that remains is your answer.

Before confirming, verify.

This article emphasize the importance of questioning baseline equivalence in comparative reasoning. Many arguments assume that two groups began from the same starting point, which can lead to flawed conclusions. To avoid this trap, always check for pre-existing differences, confounding factors, and selection biases before attributing outcomes to a single cause. Practicing this discipline through GMAT simulations helps refine logical precision, ensuring that you recognize hidden assumptions and strengthen your ability to evaluate arguments with clarity and balance.

In life, as in reasoning, clarity often comes from questioning the foundations rather than rushing to the conclusions. When we overlook baselines, we risk building judgments on unequal grounds, whether in solving Critical Reasoning questions, preparing for essays, or evaluating professional choices. This awareness is not limited to GMAT mock practice; it extends to MBA applications and leadership decisions, where recognizing underlying contexts is essential. By training ourselves to probe deeper, we learn to see beyond appearances, making choices grounded in fairness, precision, and a genuine understanding of cause and effect.